What’s the best way to tell area residents about plans for a new asylum shelter nearby?

The government should tell communities directly about plans for new asylum shelters, some activists and politicians say.

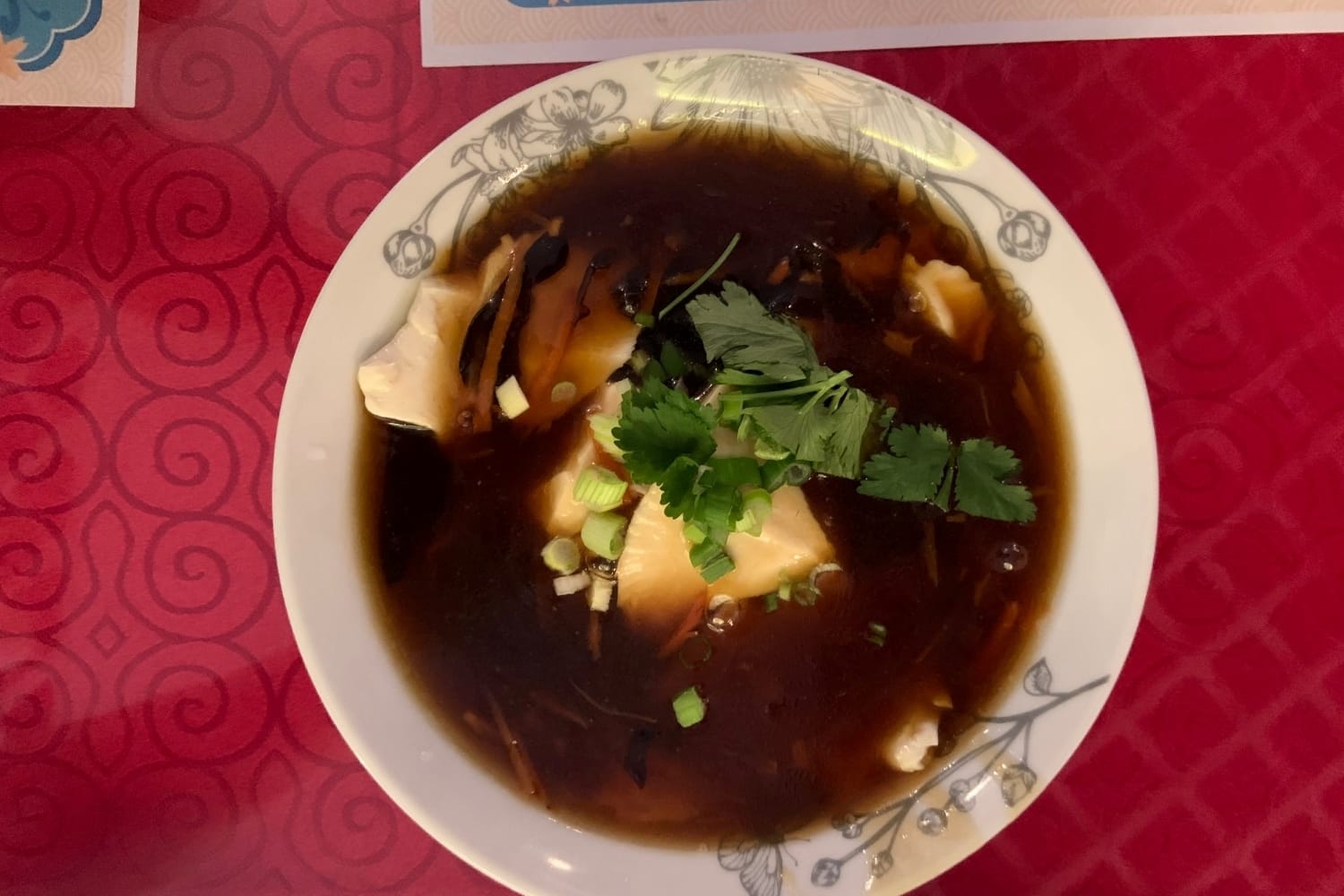

Shi Wang Yun has congee, fried dough and tofu in soup on its morning menu.

Shi Wang Yun’s humble, red and beige facade fits in effortlessly among Parnell Street’s many Chinese restaurants. It has three windows and one main door, and the sign is written in both English and Chinese.

Inside are eight tables with red tablecloths, three of them on a slightly raised floor. The place is small, but still airy.

“Our restaurant has only a few tables,” says Yang Jie, who has owned the place for two years. “We are small.”

On each table, there’s a breakfast menu written in Chinese. There’s no English version.

“That’s because only Chinese people and people from Asia eat this kind of breakfast,” says Jie.

A bowl of congee, swimming with bits of pork, fermented egg and scallions, is priced at €3. Alongside a strip of deep-fried dough, almost churro-like, which is listed on the menu for €1, it makes a filling breakfast.

“People don’t want to spend too much on breakfast,” says Jie. “And we want people to try the traditional Chinese breakfast. We always give good portions and want to keep it affordable.”

Alice Chau, a cat behaviourist who also runs Chinese food tours in Dublin as a hobby, to be able to share her passion for Chinese food with an Irish audience, noticed the restaurant as she lives close by and passes by often.

“Recently, I discovered they open in the morning and noticed a breakfast menu on their shopfront,” she says.

“The restaurant has no website, no fixed line, is difficult to find and has no English on their breakfast menu. I think a lot of people enjoy the hunt!” she says.

For breakfast, patrons mainly include Chinese people and other people from Asia for breakfast, Jie says. Other locals and tourists pour in from the afternoon onwards, when an English menu is passed around for lunch and dinner.

Jie grew up in Yunnan in southwest China. But “Shi Wang Yun specialises in food from the north side of China,” she says. “It’s very authentic.”

The restaurant has been around for over five years. Jie bought it a couple of years ago.

“I think we are on the way to achieve what we set out to do but we still have many changes to make to improve our business,” she says.

“We want people from different countries to experience something different, especially the breakfast. Some people are curious about traditional Chinese breakfast,” she says. “Most Chinese restaurants on Parnell Street don’t serve it.”

Chau says she has noticed a morning clientele. “I notice that during the week there are a lot of working types in there. I could see that they are having breakfast quickly then heading to work.”

Han Yang on Parnell Street serves Chinese breakfast too, but as a buffet, says Mei Chin, a Dublin-based Chinese-American food writer who has won the James Beard Foundation’s MFK Fisher Award.

“You’ve got a big pot of congee and you can add other stuff like the bun. It’s from 8am–2pm, word of mouth, €10 per person, all you can eat,” she says. “It’s always busy, always Chinese people.”

Dishes on the breakfast menu at Shi Wang Yun include soft tofu in soup, handmade Chinese buns filled with carrots, cabbage and vermicelli, and shredded seaweed and turnips tossed in chilli, garlic and coriander.

The Chinese buns are like large, doughy dumplings with a salty filling; the seaweed and turnips have been julienned and have a hint of spice.

The tofu soup is priced at €3.50, the Chinese buns at €2 each, and the seaweed and turnips at €3.

Each of these two Chinese breakfast options on Parnell Street is cheaper than a full Irish breakfast, which easily costs more than €8 at most establishments.

“I was surprised by the price list; it is very affordable. The first time I ate breakfast there, it was under €5. In fact, it was €3.40, and I had 3 items!” says Chau.

“Cheap” has been a stereotype associated with Chinese or “ethnic” food for a long time. An informed diner wouldn’t dare expect French food for less than €5.

“The notion of cheapness and authenticity have intersected,” says Chin, the food writer.

“Chinese food is undervalued everywhere. It’s maybe more undervalued by the Chinese themselves,” she says. “There is also this thing of white people going ‘ethnic food should be cheap’.”

“But in Dublin, you can’t undervalue it too much because importing ingredients is so much more expensive here than in the US,” she says.

Chin says that as a Chinese person, she attributes a certain amount of value to herself. “If a restaurant served sea bass in blackbean sauce at, say $35, it would make me value myself and my culture more,” she says.

In his book The Ethnic Restaurateur, Krishnendu Ray demonstrates how the reputation of Japanese cuisine has gone from being “ethnic” to “foreign”, writes Scott Alves Barton, in a review of the book.

“Much of the rise and fall is predicated upon public perception, which includes service style and standards, dominant ingredients and technique,” writes Barton.

The US restaurant guidebook and rating system Zagat found that the average price for a meal for one (including one glass of wine and a tip) at a Japanese restaurant was $68.94, whereas the average price for a similar meal at Chinese restaurants was $35.76 in New York in 2015.

This culinary hierarchy could be attributed to the fact that Japanese food has gone on to become haute cuisine, with more Japanese restaurants receiving Michelin stars. Like Ichigo Ichie in Cork, which is known to merge Japanese techniques with Irish produce.

Chinese restaurants in Dublin vary in price-setting. China Sichuan in Sandyford specialises in traditional Chinese food, but has steeper price tags. Starters at China Sichuan begin at €8.25.

“You go to Ka Shing or China Sichuan and the margins are higher,” says Chin, the food writer. “Local meats, etc. are expensive. An affordable model would have to be funded by something else rather than just the restaurant.”

Shi Wang Yun prides itself on home-style food, says Jie. “We want to show people what real Chinese food is and give them an experience like they’d have in China, and that not much has changed, and make them feel like they are at home.”

Get our latest headlines in one of them, and recommendations for things to do in Dublin in the other.