What’s the best way to tell area residents about plans for a new asylum shelter nearby?

The government should tell communities directly about plans for new asylum shelters, some activists and politicians say.

The stories told by working-class women in inner-city Dublin that are included in Kevin C. Kearns’ book have acquired a new resonance in contemporary Ireland.

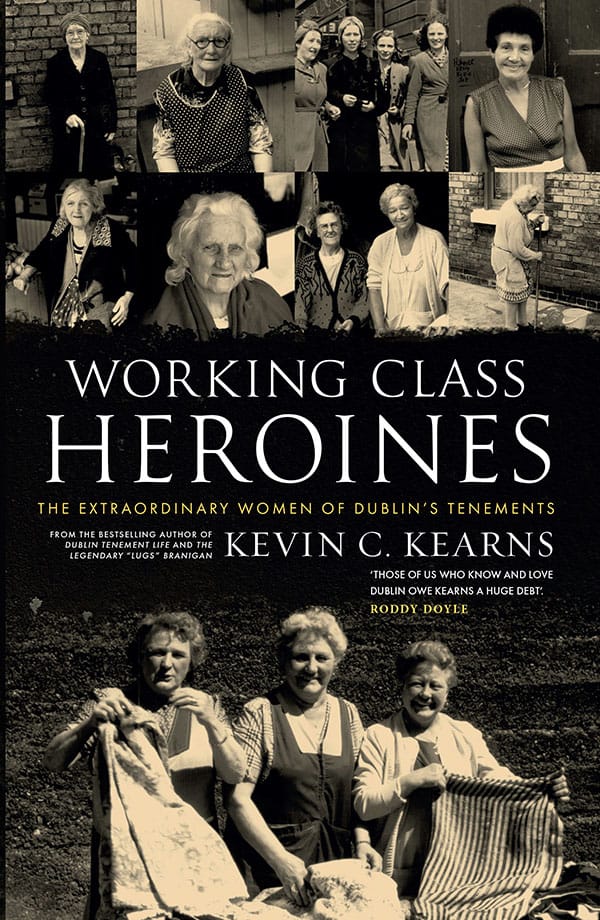

The stories told by working-class women in inner-city Dublin that are included in Kevin C. Kearns’ book Working-Class Heroines have acquired a new resonance in contemporary Ireland.

It might even be fair to say that this book resonates more strongly today than it did when it was first published in 2004.

In the wake of the Repeal the Eighth and Take Back the City movements, these oral histories, with their stories about women fighting for bodily autonomy and a right to housing, highlight the origins of contemporary struggles.

These narratives offer a framework through which we can judge how far we have come and how far we have yet to go.

Working-Class Heroines is the result of more than 30 years of research, a compendium of detailed oral history documenting the oft-forgotten details of working-class life, with a particular emphasis placed on working-class mothers.

It was something of a “pioneer path” more than 50 years ago when, in the 1960s, Kearns set out to be an urban oral historian, he said, by email.

Back then, Irish academics “associated oral history and folk history strictly with the west of Ireland, especially the Gaeltacht regions”, he says.

Yet there he was, “exploring the lower-income working-class neighbourhoods of Dublin that Irish journalists used to call slumlands,” he says. “From the Coombe through the old Liberties and into the tenement rows of the northside.”

In Working-Class Heroines, Kearns uses the narratives gleaned from urban “mammies” to construct a case for their reinsertion into the larger narrative of Irish social history, and to ensure that their stories of survival are not relegated to the footnotes of Irish femininities.

“Back in those days women were absolutely ‘voiceless’”, Kearns says. “And they dare not try and speak out against their husbands or any man […] I found the women so pathetically abused and defenceless in those days. So I determined to try and tell their stories in their own words.”

The word “mother” is laden with symbolic meaning in Ireland’s national discourse. It is a concept wrapped up in images of Mother Ireland, a figure chaste and maternal, sacrificial and tenacious.

The mothers interviewed in the book occupy a particular space as a result: the concept they embody, that which is devotional and pure, is at odds with the reality of their lives. They are admonished, abused and neglected – at home, and by the state.

The book is divided into chapters detailing everything from home, family, finances, sex and marriage, to religion, drugs and death. Throughout, Kearns interrogates the societal pressures placed upon urban mothers.

As Kearns tells it, the origin of their plight lies in the “flight to the suburbs” by middle-class families that occurred in the 19th and 20th centuries, which left lower-income families to live in a decaying city centre, raising eight or ten or twelve children in cramped quarters with no more than two or three rooms.

Often, the women of these urban families were expected to marry young and begin to care for children almost immediately. It is here that the traditional narrative of family life begins to unravel: what was propagated by the state was the husband as breadwinner, with the wife as stay-at-home caregiver.

However, as Kearns documents here, for working-class “mammies”, this was rarely the the reality. Husbands faced constant layoffs. Some squandered what little money they had on alcohol or gambling. This left women to rear the children and make ends meet. Many had to find menial cleaning and care-taking jobs.

As Dr James Plaisted, an inner-city doctor for over 40 years, says in the book: “[Mothers will] get up at six o’clock in the morning and go in and clean offices, and they’ll be home to get the children up and fed and out to school.”

The day isn’t over yet. “And then they’ll do their work in the house and do the shopping. And the man, if he’s unemployed, he’ll lie in bed until 11:00 and do nothing […] Your woman fed him and she’ll be back at half five in the evening to clean offices again,” he says.

Working-class mothers were just expected to “get on with it”. Husbands were granted freedoms of which their wives could only dream. Many men would rather become distant from family than have their pride wounded by being seen to help with household chores.

In one notable exception, Kearns quotes Lily Foy, a woman who grew up in the Coombe watching helpless men neglect family and home, and who married a man quite liberated for the 1950s, who helped with cleaning, cooking and washing.

However, his helpful attitude was taken as “woman-ish”, and Foy’s mother took to calling him “Molly the Piss”. Distress, an ever-present facet of working-class inner-city life, was expected to fall squarely on women’s shoulders.

Reading Heroines, you begin to see how little autonomy mothers had. While many suburban mothers had access to better education and information around sexual health, and so some limited autonomy, many inner-city mothers were bullied and much more closely controlled.

This control could manifest through bodies such as the church and the state. Mothers, who took to looking after money and finances due to neglectful husbands, were often under the thumb of the Dublin Corporation.

The “Corpo”, as it was known, was responsible for social housing in the inner-city. It was notoriously ruthless in demanding rent, often employing eviction crews or local gardaí to help with the forced removal of tenants.

In one harrowing case documented in the book, “the Corpo” forcibly removes an elderly woman who is suffering from dementia. She had lost her husband, her mind had deteriorated and she couldn’t pay the rent. She was thrown out and left to wander Foley Street.

To the church, another controlling force, women were seen as little more than baby-making machines, and were encouraged – nay, forced – from the pulpit and confession box to have multiple children.

Women with 10 or more children were encouraged to have more, in spite of dwindling finances or heavy physical and emotional toll. Childbirth was viewed as maternal duty rather than personal choice.

Kearns documents how some women were turfed out of the confession box for admitting they could not bear any more children. He interviews May Cotter, who says she was often asked in the confessional why she was not having more children, a question she found invasive. “Didn’t matter if you had the wherewithal or not to feed them or rear them,” she says. “You just had to keep populating the country.”

Meanwhile, sex was a subject not spoken about or acknowledged. And even though they were in charge of home and finances, women were subordinate in matters of intimacy. “The man dominated. Always. Do your duty! His word was absolute law,” says one working-class mother.

“[There was] nothing romanticized in their oral histories,” says Kearns via email.

“Emotions bared as never before […] And, God forbid, how some bared their anger toward the priests who terrified and condemned them in their younger years! Their faces turned flaming red as they told me every detail. How the husbands were tyrants in the home – and absolute demons in commanding their wives in bed!” he said.

Kearns uses Yeats’ poem “The Song of the Old Mother” to sketch an understanding of these women’s lives.

He might, these days though, have used a different Yeats poem. Indeed, in documenting the stories of these “mammies”, Kearns offers us an opportunity to gauge how things have “changed, changed utterly”. And the ways in which they have not.