What’s the best way to tell area residents about plans for a new asylum shelter nearby?

The government should tell communities directly about plans for new asylum shelters, some activists and politicians say.

The new version of their project, now called “Tender”, involves distributing postcards that people can send to the gallery to share their views on the situation.

After the rain on a Friday evening, sunlight fills the Grey Square courtyard in the National College of Art and Design (NCAD) on Thomas Street.

A student plucks dirt from the plughole of an upside-down silver bathtub. Another plays a vague melody on an out-of-tune piano in the Concourse, a student area.

Members of the master’s course Art in the Contemporary World (ACW) leave the Harry Clarke Building following a meeting concerning their upcoming project, Tender.

Among them is the harpist Méabh McKenna, who strolls across the square towards the Concourse with a fellow student and paper bag of pastries. The pair take a seat at a picnic table covered in Sharpie tags and Simpsons caricatures.

Tender, McKenna says, is an interrogation of the National Gallery of Ireland and Aramark, the multinational corporation, which operates three direct provision centres for asylum seekers in Cork, Clare and Westmeath.

Sixteen students have designed 20 postcards, which examine the ethical implications of the gallery’s awarding of a three-year café contract, worth €7.5 million, to Aramark, and the broader human rights issues levelled against the state’s system of accommodating asylum seekers.

Due to be launched in NCAD on 19 May, according to the module’s co-ordinator Nathan O’Donnell, the postcards are to be freely distributed via order from the ACW with the intention of being sent to the gallery.

Prior to the realisation of Tender, the module from which the idea sprang was intended as a collaboration between the National Gallery and NCAD. But during its development, the gallery withdrew its funding, a GoFundMe page for the project says.

The project stems from a hope that our cultural legacy, kept within the gallery, is handled with an ethical tenderness, McKenna says. “With a human element of kindness.”

“If you work in fine arts, I’m sure at some point you hope to work within or around the gallery,” she says.

“So, to have that corrupted in such a visceral way and ethically, that’s the big question which we’ve kept coming back to. Is the gallery an ethical body? And what is its position in presenting our aspirations culturally?”

The National Gallery of Ireland declined to comment on the withdrawal of the budget, the decision to conclude their collaboration with the Art in the Contemporary World module, and its awarding of the contract to Aramark.

An Aramark representative said it is proud of its work in the three services that it operates on behalf of the state, “with no link to the other 45 centres”, adding that their services are accredited to internationally audited standards.

Tender emerged from a 12-week module in the Art in the Contemporary World course, titled “Museum metabolisms, collections and futures”.

The module was designed to consider how activism and artistic intervention has reshaped the practice of museums globally.

According to painter and student Leda Scully, the objective was to reflect on a wing of the gallery, and critique its architecture, collection and the broader context of the gallery.

“In previous years, they looked at the Shaw Room and responded to it by making a newspaper,” Scully says.”

For 2022, she says, they were to analyse and investigate the Dargan Wing.

Beside Leinster Lawn and facing Merrion Square, the Dargan Wing is the gallery’s oldest portion, completed in 1864.

According to O’Donnell, they looked into questions such as representation and the ethics of patronage.

“We were looking at the complexities of the gallery and the Enlightenment origins of the Dargan Wing,” he says.

On the ground floor of the wing is painter Daniel Maclise’s enormous, nightmarish depiction of Strongbow’s marriage to Aoife MacMurrow in 1170. The Norman militarist’s foot is on a fallen Celtic cross. Aoife’s father Dermot, the king of Leinster, has a look of horror on his face.

Upstairs in the aqua-green Grand Gallery is a slew of portraits of earls and countesses.

In one allegorical work, William of Orange triumphantly straddles a white horse beneath the God of War and the Goddess of Plenty.

Another depicts the earl of Ely’s family at their home in Rathfarnham. In the corner is a young Indian page, hunched over, carrying two coronets on a cushion.

Scully says she will probably never be able to look at the collection in the same way as she had prior to the course. “A lot of the collection is steeped in blood.”

“I don’t want to sound dramatic about it,” she says. “But if you go in and look, there are paintings with slaves in them, children that were taken away as a kind of folly for the upper classes.”

Says Scully: “That was the focus of our critique if we had stayed working on it.”

The module began on 4 February. But their focus shifted when, O’Donnell says, the students became aware that Aramark was assuming charge of the café.

In a letter to the National Gallery’s Board, staff expressed “deep distress and strong opposition” to the café contract.

The signatories wrote that they believed Aramark’s “values and work practices are at odds with those upheld by the National Gallery and its staff, and that their presence here will cause irreparable reputational damage.”

Later, in February, three artists shortlisted for the 2021 Zurich Young Portrait Prize – Brian Teeling, Emma Roche and Emily O’Flynn – requested the removal of their works from the gallery.

Teeling, a photographer, says that as well as pulling his work, Declan Flynn in Dublin, he also withdrew from a lecture he was due to deliver.

“For me, the whole point of the National Gallery is that it’s a revered space where you can go and see classics, these masterpieces by incredible artists,” Teeling says.

“You can’t award a café to a company that profits from direct provision, a racist government policy, this government’s policy,” he says. “You can’t do that.”

Teeling found the award of the contract to Aramark particularly galling, after the gallery previously hosted the exhibition Something From There in late 2020, featuring work from people living or formerly in direct provision.

“They’re willing to go and do something like that for kudos and media coverage,” Teeling says. “What a slap in the face.”

According to a proposal document for Tender, on 18 February the students toured the wing’s architectural features, but they were already preoccupied with Teeling’s action.

His vacant space had been replaced with another piece, Portrait of Uachtarán na hÉireann, Michael D. Higgins by Sarah Doyle.

By this stage, the original plan to investigate the Dargan Wing didn’t resonate anymore with them, says student and writer Lara Ní Chuirrín.

“Our two module co-ordinators just asked us if we wanted to pivot the project and we all jumped at the opportunity,” she says.

Co-ordinator O’Donnell says they felt it impossible to overlook these developments.

“All of this was consistent with what we’d been looking at,” he says. “We couldn’t ignore it, because that would have been doing a disservice to the module and material.”

On 10 March, the National Gallery’s director Sean Rainbird issued a statement, saying that some staff and groups from the arts and academic sphere were critical of the result of the tendering process.

Rainbird said that he sympathised with people’s concerns about the system of Direct Provision, while saying the Gallery had shown a commitment to people in Direct Provision through the Something From There project.

Separately, he said, the gallery has a service agreement with Aramark, which was “correctly procured”. “It will disappoint some, but the café tender process has been run correctly and the result is one we abide by.”

According to the Tender GoFundMe page, the National Gallery withheld a budget of €2,900 for the Arts in the Contemporary World course’s “Museum metabolisms, collections and futures” module.

O’Donnell says the gallery told him that “they didn’t want to enter into a situation where they were having to censor the students’ work”.

Alternatively, he says, the students proposed that the gallery donate the money to the Movement of Asylum Seekers in Ireland (MASI) instead.

But ultimately, O’Donnell says, the gallery declined this idea.

A spokesperson for the National Gallery of Ireland said they would not comment on these matters.

An Aramark spokesperson said decisions about the National Gallery’s partnerships are a matter for the gallery.

By 28 April, the Arts in the Contemporary World course’s crowdsourcing of Tender hit its target of €1,500, before eventually reaching €2,760, with a promise of donating the excess funds to MASI.

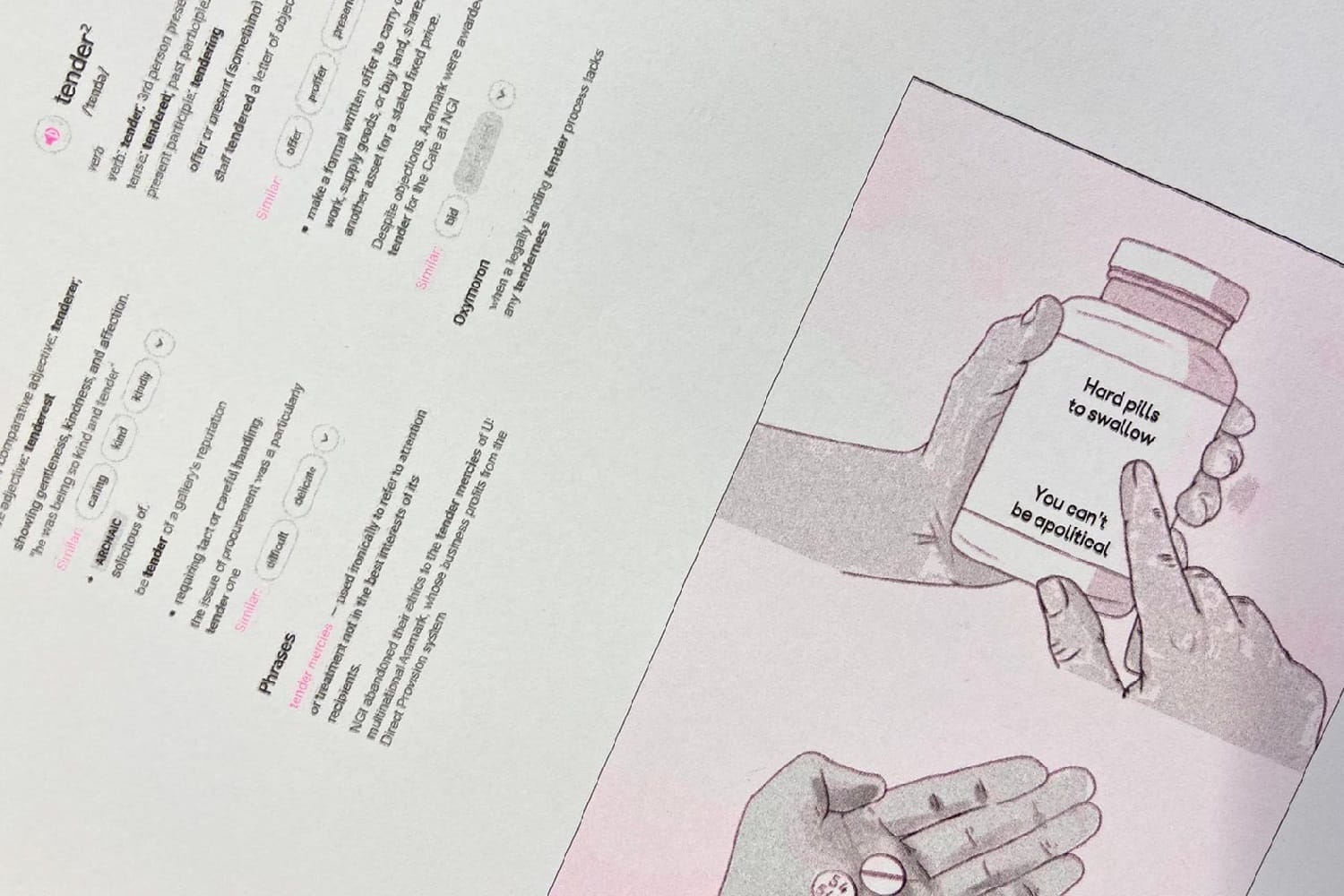

The postcards, Ní Chuirrín says, are riso-printed and based on designs from the 16 students in the course. “It was inspired by gallery gift shops and it was a riff on that.”

One is a parody of a Google error page: “The National Gallery of Ireland is regretfully not open to institutional critique at-present. Please check again in four years’ time.”

Another card plays around with dictionary definitions of the word “tender”, using example sentences such as “NGI abandoned their ethics to the tender mercies of US multinational Aramark.”

A third quotes the findings from a 2014 report published by Cork-based organisation Nasc Migrant and Refugee Rights observed that asylum seekers described their food as “inedible, monotonous, too strictly regulated and culturally inappropriate”.

A representative for Aramark says the findings from this report do not reflect nor reference the company’s own services or standards in quality.

They say, for the last eight years, Aramark sites have held resident focus groups on menu options to ensure meals are culturally diverse and sensitive.

Some of the other postcards directly critique the National Gallery, Ní Chuirrín says. “There are others that question the role of the museum, that examine the role of the museum and the conditions in direct provision centres. There are memes and serious ones.”

Ethical and moral consumption, Ní Chuirrín says, is one of their focal points in the project.

“It’s not necessarily calling for a boycott of the gallery or cafe. It’s more a presentation of information as we see it,” she says.

McKenna says that, fundamentally, their aim is to bridge a gap between public discourse and curatorial critique.

“The idea of the postcard is that this is an invitation to communicate with the gallery,” she says. “You are invited to write in response to the situation.”