What’s the best way to tell area residents about plans for a new asylum shelter nearby?

The government should tell communities directly about plans for new asylum shelters, some activists and politicians say.

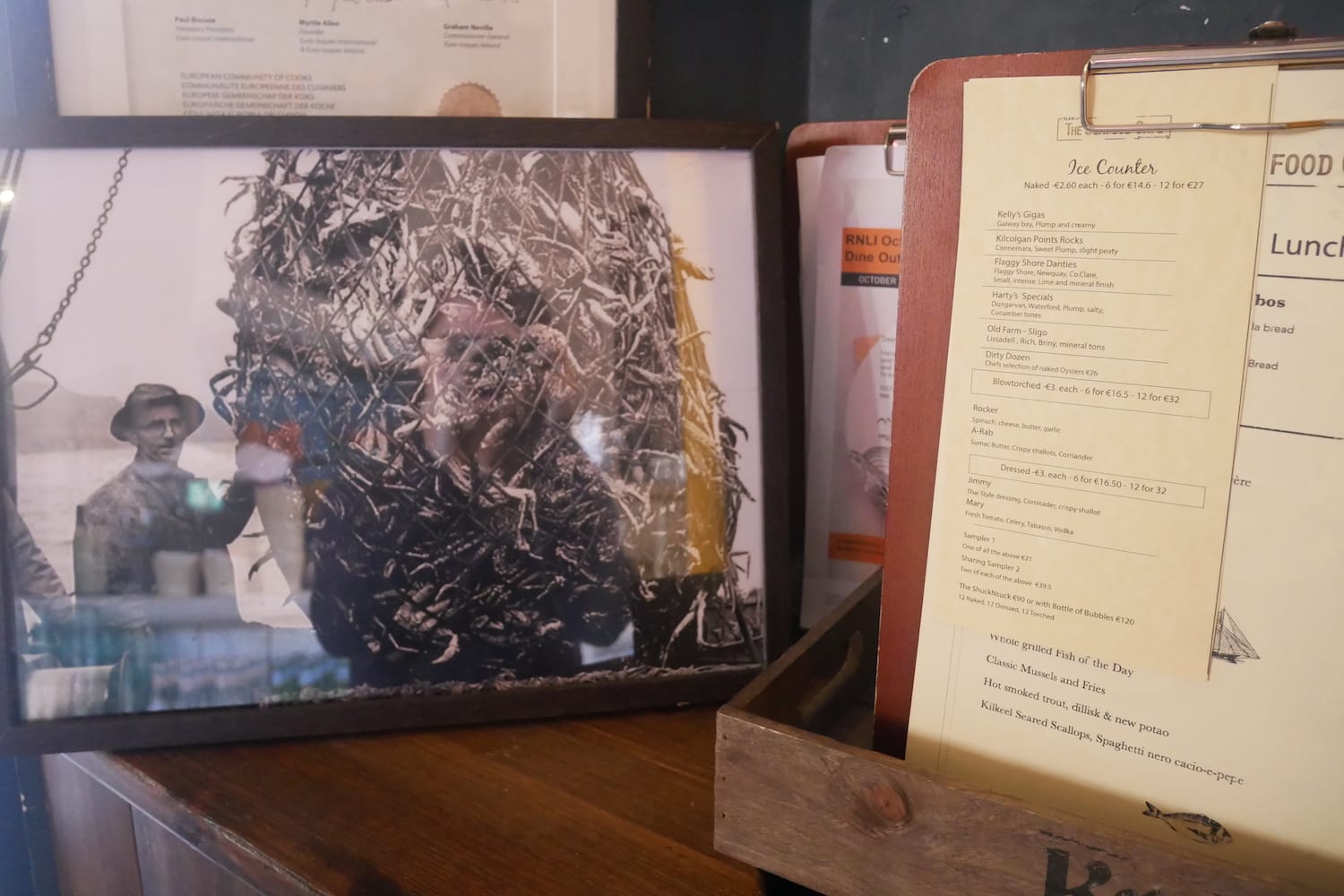

The Food Smart Dublin project aims not only to reintroduce forgotten seafood recipes to the Dublin diet, but also to show why its smart to use some seafoods more than others.

Chef Niall Sabongi plans to add his new fish-head terrine to the menu soon, he says. Or perhaps a many-fish-heads terrine, depending on how playing around in the kitchen goes later.

“I’m going to do a mixed-head recipe this week,” he said, on Monday morning at The Seafood Café in Temple Bar.

Perhaps it’ll feature cod, hake, and haddock. “What I’m hoping to get is a kind of layered marble effect running through it,” he says. “So you get different textures in your mouth.”

A cod-head terrine was the first dish that he rustled up based on an old Dublin recipe as part of the Food Smart Dublin project. And it’s the first of many he intends to make, with the help of his colleagues.

Sabongi is working on alongside academics at the Trinity Centre for Environmental Humanities, including marine ecologist Cordula Scherer, who share the goal of reintroducing forgotten seafood recipes to the Dublin diet.

Another goal is to show how seafood consumption can be sustainable – not only by using all parts of a fish, as in the terrine, but also by eating fish and sea vegetables from lower layers of the ocean.

Fish, sea creatures, and plants in what are called lower-trophic levels take less energy to form than the bigger fish in the higher-trophic levels which are mostly what we eat today, says Scherer, also in The Seafood Café.

“We want to tap into these guys here, down here,” she says, pointing with a pen at a rough chart of ocean layers. “They grow within days and weeks, but tuna takes ages to grow – and the energy that goes into it.”

Imagine food pyramids for land and sea, and the further you go towards the tip, the greater the energy that it takes for fish or organisms to be produced and grow.

In the sea, you would have phytoplankton and algae on the bottom level – and then krill, and zooplankton one level up.

“Plankton comes from the Greek and it means drifting – because they have too little power to swim against the current and swim actively, so they’re drifting with the current of the ocean,” says Scherer.

Step up another layer and there’s herrings and lobsters. “Everything that feeds on your two lower levels,” she says.

Right up top? The bigger fishes. “Your tuna, your salmon, your cod,” she says.

Meanwhile, the lower levels on land would be plants and shrubs, and one level up would be chicken and cows – the beasts that eat them. At the top, are lions and tigers, says Scherer.

“What we want to do is to make people aware that in the sea, we are really happy to eat tuna and salmon and cod, but we would never dream of eating lion, tigers on land. How is that? And why is that?” she says.

The top layer of fish is just 1 percent of the food in the ocean – and it takes about 3,000kg of lower-layer stuff like phytoplankton to make 300g of tuna, she says. “That’s the energy that goes into this.”

The old Dublin recipes they’re drawing on are mostly from collections in the National Library of Ireland, says Scherer.

They’re in English so they likely only mirror the diet of more elite Dubliners, she says. “They might not represent the broad, the majority of people.”

Some of the commentary suggests that too. “There are often actually references to, actually, oysters are for the poor. Or eel is not a very favourable fish, but it’ll do for the poor,” she says.

The terrine that is shortly to appear on the menu at The Seafood Café evolved from a fish-head soup recipe from the 1700s, found in the Townley Hall Papers.

Sabongi says he was testing the original recipe, teasing out the flavours, when he put it aside and the cold soup set into a terrine.

“It reminded me of a brawn, an Irish dish made with pig’s head,” he says. So he ran with that.

He made some changes, taking out non-indigenous ingredients such as mace, nutmeg and lemon.

“A lot of the time, people use a lot of lemon in seafood to disguise the flavour of the seafood,” he says. But for fresh good seafood, there’s no need.

Instead, in the terrine, he used pepper, salt, herbs and lovage. “I picked things that would have grown in the area,” says Sabongi.

Sabongi says he can remember a time when his dad would bring bags of crabs back to his home in Clontarf.

“We’d sit there on the front porch with big domestic hammers smashing them,” he says. “Some fisherman would have given a big black bag of them.”

His dad was Egyptian and seafood would feature heavily in Egypt’s cuisine, says Sabongi. He laughs. “The neighbours used to walk by, saying, ‘Would you look, the poor foreigners,’ you know. ‘Haven’t got a bit to eat, eating that stuff from the beach’.”

But back then, Dubliners ate more varied species, he says – they’d fish as kids in Dublin’s rivers, not catching much because they were terrible fisherman.

“But you’d always catch eels and we’d eat the eels we’d bring home. We’d cut them up and fry them in butter,” he says. “It was just delicious but you don’t see that anymore.”

Meanwhile, dogfish, also known as rock salmon, was close to a staple, too. “A rock and chips was really common. You’d find it in every chipper in Dublin,” he says.

Bringing some of those sustainable lesser-eaten fish back is a big part of the projects’ aim, he says.

“We used to always eat within seasons,” he says. “And eat locally as well. So I’m trying to do that, to keep everything within a 30-mile radius and everything that’s really in season.”

Sabongi has a wholesale company so he sources everything from small boats and fisherman, he says. “Everywhere really from Waterford, to Donegal, to Sligo, to Cork to Galway. All around,” he says.

Scherer says she wants to try to address the question of how normal people can source different fish and sea vegetables, if they aren’t so well-connected.

Says Sabongi: “I think it’s asking. You know, people will start seeing that there is a demand for it, and with demand comes commercial viability and all that.”

Sabongi gets down a folder of printed out old recipes from a high shelf near the restaurant door, and flicks through it, as he talks.

There are printed pages from Maria Rundell’s A New System of Domestic Cookery, from the early 1800s.

He has plans to try to use periwinkles, cribbing from an old French recipe for roasted bone marrow that uses snails in garlic butter, he says. “It’ll be nice actually, tasty.”

A turbot recipe has caught his eye, too: poached turbot in a lobster sauce. But, in his version, it’ll be with velvet crab and anchovy butter, he says. “It’s going to be really nice.”

Scherer says that eventually they’ll have tasters of the dishes they create, too. “To collect data, to see how people respond to all these different tastes.”

[CORRECTION: This article was updated on 13 November at 12.22pm, to correct the name of the Trinity Centre for Environmental Humanities.]