What’s the best way to tell area residents about plans for a new asylum shelter nearby?

The government should tell communities directly about plans for new asylum shelters, some activists and politicians say.

Carl Hickey lurks with a camera, recording images he’ll later commit to canvas: men with traffic cones on their heads, Spiderman brawling, a khaki-clad crowd.

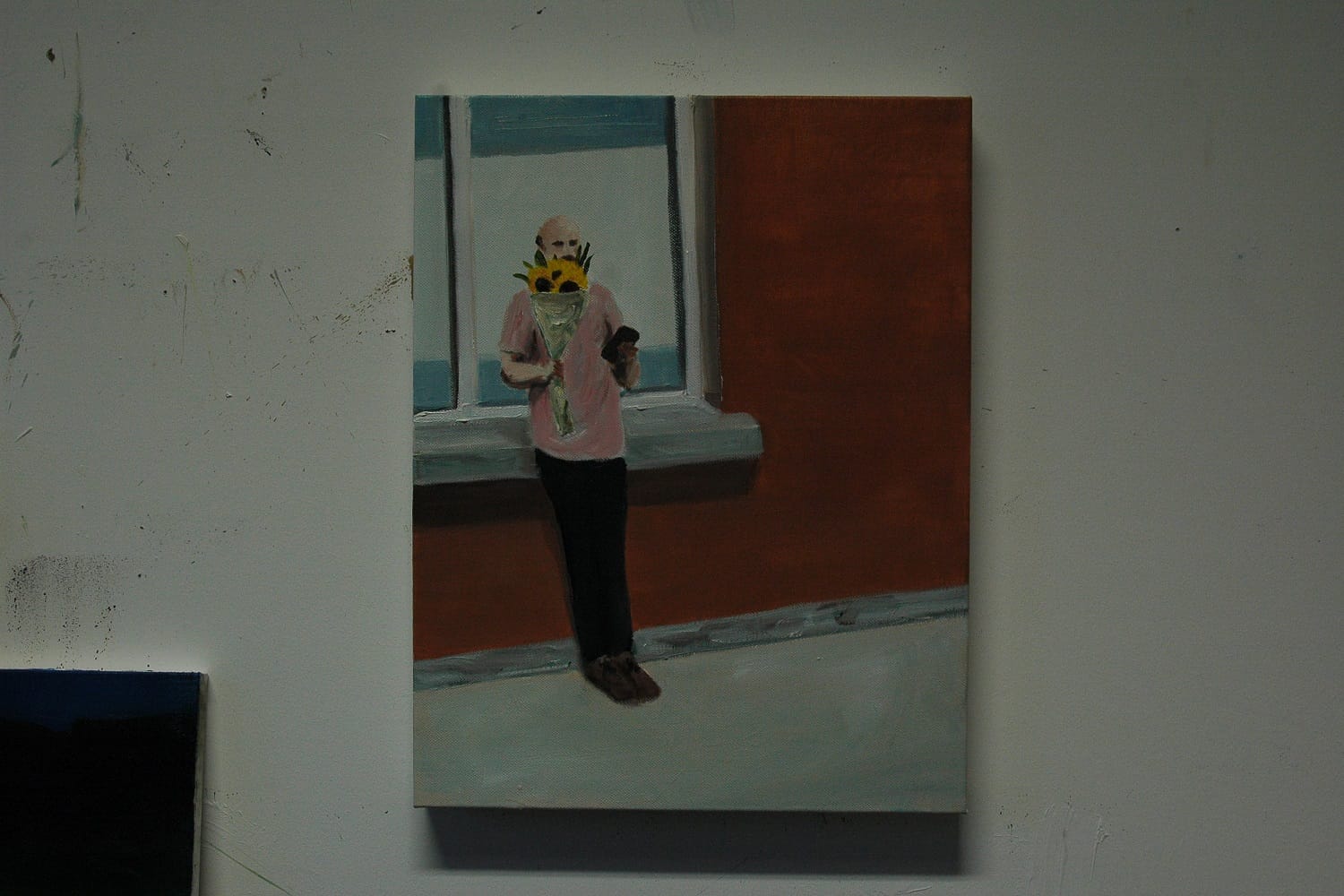

Carl Hickey has hung an oil painting in the corner of his studio by the door.

It shows a man leaning against the window sill of a red-brick building, staring off into space and clutching a bouquet of sunflowers.

The figure appears oblivious to the fact that he is being observed. Titled Flower Boy, the work is an impressionistic recreation of a video that Hickey took one day.

To accompany the portrait, the artist wrote a short text, jotted down on a sheet of paper, torn from a notepad. “A bloke with flowers is usually really guilty or really in love – or both,” it says.

The painting is one of several that decorate Hickey’s studio, a utilitarian space, filled with few non-work related objects, among them a single potted plant, which sits in the open window, overlooking the bars and cafes along Chatham Row.

Each painting offers a brief glimpse into the life of one of Dublin’s inhabitants as they go about their day, unaware that these transient moments will be committed to canvas.

Resting against the wall next to the door is a garda running towards something outside the frame. Hung above that is a landscape. There is a boy in the foreground, his back turned away as he watches a car veering off a road onto a stretch of grass in Tallaght at night.

From among a trove of smaller pieces, Hickey picks out a work depicting a man holding a big white dog in his arms outside the Centra on Dame Street. At first, people often mistake the dog for a sheep, he says, laughing.

Hickey likens his output to a kind of artistic surveillance, he says, while sat at his desk, on which a laptop and a printer sit. Blu-tacked to the walls above it are A4 print-outs of candid stills of his subjects.

“I like to make work from what I’m surrounded by, because it makes you feel content with what’s around. Every day is like a new possibility that something can happen out of a normal thing.”

Reaching up to a cork board beside these sheets of paper, he unpinned another of his notes, written in biro. “Do they know they crossed my mind, the odd time, questioning their existence?” it reads. “Am I on some stranger’s mind?”

As 24-year-old Hickey sat in his studio, last Friday evening, he brimmed with energy, his legs bouncing on the balls of his feet. He wore a blue shirt, short-sleeved and caked in layers of dried oil paints.

All of his focus was on preparing for an upcoming solo exhibition at the Atelier Now gallery, opening on 16 March, he says. By the printer on his desk was a can of Red Bull.

Taped to the surface of another tabletop was an A1 sheet of paper he used for mixing colours. In the windowsill was a Cadbury’s Creme Egg mug loaded with paint brushes.

Hickey had been stowed away in here for days on the top floor of the Dean Studios, he says. Nights are spent priming canvases for the morning after.

The show is highly personal, he says. “It’s more personal than any work I’ve ever made, and I’m hoping not all of this resonates with people, because then it’s not all me.”

He nodded to a work-in-progress by the window, which is a self-portrait of sorts, he says. Two figures approach a house, wearing a pair of wigs, one blue, one pink.

It is Hickey and a friend of his, recorded as they are knocking on a front door, he says. “I don’t really paint myself, because it’s usually my footage. But it’s us just messing around. I’m thinking about my past a lot at the moment, and that’s just an example of one good moment.”

While he rarely uses his own image as a reference, Hickey says, increasingly he has begun to see in other subjects parts of himself.

He refers back to the landscape of the car as it races across the parklands outside Tallaght, leaving a trail of skid marks. It has become an almost autobiographical scene by proxy, he says.

The young boy in its foreground isn’t Hickey. But he sees himself in the character, he says. Scenes like this used to occur where he grew up in Clondalkin. “It doesn’t really happen in my area now because the fields were dug up.”

“I was that kid once, looking at that,” he says. “I can’t watch it anymore, but the kid still can, because nothing was added to his own area.”

Growing up in Clondalkin, Hickey had not intended to pursue art, he says. “In school, English would’ve been my favourite thing because I was into writing, and I was really into hip hop, reading into those words.”

After secondary school, he enrolled in the National College of Art and Design. But “I thought it was going to be a flaky thing”, he says.

His first thought was to train as a sculptor because he had experience in woodwork and construction, he says.

But two or three weeks in, he decided he wanted to paint, he says. “And as soon as I picked up a paintbrush, I decided that I wanna do this.”

He first experimented with reimagining digitally manipulated photographs as paintings. Later, he gravitated towards crime scenes as a subject. “When you Google where I’m from, all those images were the first results you’d get.”

During the pandemic, his gaze shifted again. He depicted scenes from arrests and evictions. But he branched out, capturing many of the stranger-than-fiction aspects of city life.

He painted men wandering about with traffic cones on their heads. Someone brawling with a person dressed as Spiderman. Seven lads on Dame Street, all dressed in blue shirts and khaki pants. A guy stuck to the bonnet of a car as it sped onto the Custom House Quay.

An avid skateboarder for years, his creative output began to take shape as a fine-art reimagining of the chaotic, prankster-ish videos prevalent within the subculture.

“Growing up around town, we’d film our whole lives on camera, filming kids skating alongside this kind of crazy stuff,” Hickey says. “Looking back on those old videos, we were just as nuts as the people I’m recording now.”

Phili Halton, editor of the skateboarding magazine _Goblin, _says that many of the city’s skateboarders have branched out into different forms of creative expression. “Carl was one who went down the artistic route.”

Hickey’s work, Halton says, contains a lot of documentary realism. “Doing an activity like skateboarding brings you into the street, so you’re exposed to a lot of weird situations that Carl would capture.”

The work is unpretentious, Halton says. “I feel like he is good at finding something artistic in the day-to-day, even if it’s a guy holding a dog.”

His paintings are playful, says poet Chinedum Muotto. “It’s almost non-serious, but very colloquial, quotidian, this idea of daily life. It’s nothing out of the ordinary, but how he paints it makes it very out of the ordinary.”

The narrative of everyday life is what appeals to Hickey, he says. “I’m always writing in notebooks, writing down things what people would say, overhearing conversations on the streets.”

Hickey says his imagined audience isn’t the usual gallery-going crowd. So he has honed his own distinct kind of meme-like presentation, showing the finished works alongside handwritten notes and the videos from which the paintings derived.

The fleeting moments, when paired with Hickey’s own wandering thoughts, immerse the viewer in the artist’s journey through everyday Dublin, seeing what he encounters, and being guided by fragmentary musings extracted from his own inner monologue.

As humorous as it can be unsettling, at heart, Hickey’s work expresses a deep love for the city itself, he says. “I want to live and die here. I might fuck off for a year. But I want to be here, and raise kids here, because everywhere else … I can’t stand it.”