What’s the best way to tell area residents about plans for a new asylum shelter nearby?

The government should tell communities directly about plans for new asylum shelters, some activists and politicians say.

In 1918, a crowd of perhaps 10,000 rallied at the Mansion House in Dublin to herald the birth of the new “Russian Republic”, following the Russian Revolution.

Not everybody was happy with the news in January that Dublin City Council had set aside €30,000 to mark the centenary of Russia’s Bolshevik Revolution.

Young Fine Gael called on the council to “abandon its plans to commemorate the October 1917 tragedy, and to put the money it has set aside for the commemoration to better use elsewhere within the arts budget”.

The Times gave space to opposing views on the matter, in an article entitled, “Dublin keeps the red flag flying”.

Yet regardless of what one thinks of Vladimir Lenin’s seizure of power, the influence of events in Russia on revolutionary Ireland was enormous.

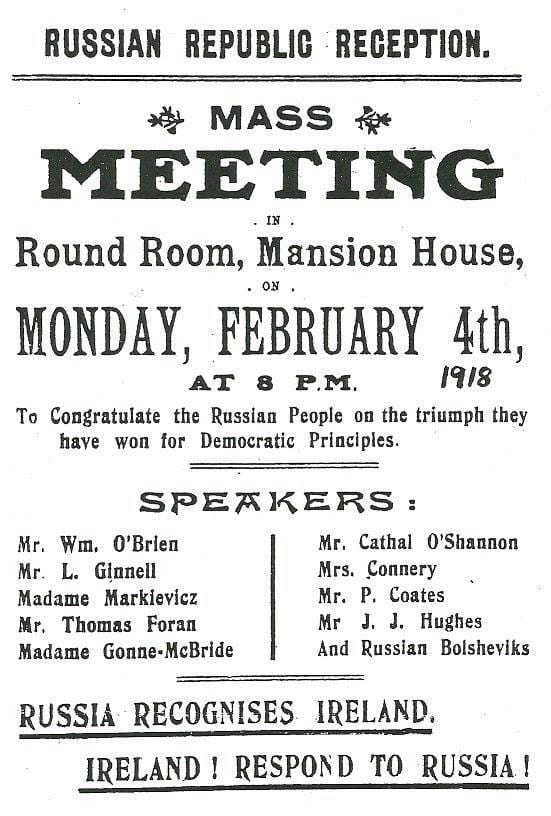

On 4 February 1918, thousands rallied at the Mansion House on Dawson Street to herald the birth of the new “Russian Republic”, and to “congratulate the Russian People on the triumph they have won for Democratic Principles”.

With a crowd estimated to be in the region of 10,000 people, the Irish Independent proclaimed that “the scene in the Round Room was an extraordinary one. The passage up the centre of the spacious and crowded floor was occupied by a dense body of men standing.”

The gathering had all the trappings of a socialist meeting, as “near the front of this body was borne aloft a red flag, and during an interval in proceedings … the song ‘The Red Flag’ was sung”.

Among those to address the crowd were Maud Gonne and Countess Markievicz. The latter congratulated the Bolsheviks on behalf of the Irish Citizen Army, which less than two years earlier had taken part in the Easter Rising.

Recent archival releases suggest that the Bolsheviks took a keen interest in the events that played out on the streets of Dublin during the insurrection.

Patrick Little, a prominent nationalist and journalist, would claim in his witness statement to the Bureau of Military History that exiled revolutionary Russians arrived in Dublin in the immediate aftermath of the Rising, and that “they knew former revolutions had been carried out, by manning the barricades in the street, but the Irish strategy was new. The taking of houses, in key positions, interested them greatly.”

Dublin’s unusual visitors were said to include Ivan Maisky, later the Soviet Union’s ambassador to Britain.

Maurice Casey, a historian with an interest in the intersections of Irish and Soviet history, has suggested that these men most likely arrived from Britain, as “at the time, a community of Russian political exiles existed in London. The delegates were almost certainly self-selected from amongst this coterie.”

Certainly, the 1916 Rising did impact on Lenin’s political thinking. Watching from afar, he said that “a blow delivered against the power of the English imperialist bourgeoisie by a rebellion in Ireland is a hundred times more significant politically than a blow of equal force delivered in Asia or in Africa.”

Against the slaughter of the First World War, Lenin believed such nationalist uprisings deserved support.

Not all Russian radicals shared his positive outlook of events in Dublin. G.V. Plekhanov described the rising as “positively harmful”, while Karl Radek, later a victim of Stalin’s purges, said that “although it caused considerable commotion, it had little social backing”.

Just what of the Bolshevik Revolution appealed to Irish nationalists, and how did they mange to fill the Mansion House to celebrate it?

Undoubtedly, the desire of the revolutionary forces in Russia to withdraw from the First World War was viewed as a serious body blow to the British empire.

Indeed, Frank Robbins of the Irish Citizen Army would recall that he and his comrades regarded events in Russia “as being the end of Russian participation in the war, and we visualised Britain’s defeat as almost certain, and our independence as a nation in sight”.

There was some diplomatic engagement between the two “republics” throughout the revolutionary period.

Patrick McCartan, essentially Sinn Féin’s Ambassador in the United States during that period, even spent time in Bolshevik Russia in the early freezing months of 1921, seeking recognition for the Irish Republic, and, recent research suggests, arms as well. He thought little of society there, remarking in correspondence to Dublin that “the idea of whether or not the present regime represents the will of the people is openly laughed at”.

By 1919, hysteric denunciations of Russia were appearing in some Irish newspapers, in particular the Irish Independent. They repeated the claims of a Catholic bishop that “it had been a matter of notoriety that Connolly was in touch with Russian Socialists … What these people were trying to do in Ireland was to bring about the same kind of disorder and revolution as in Russia.”

If the sight of 10,000 people at the Mansion House in February 1918 was anything to go by, maybe some Dublin workers had wished that were true.