What’s the best way to tell area residents about plans for a new asylum shelter nearby?

The government should tell communities directly about plans for new asylum shelters, some activists and politicians say.

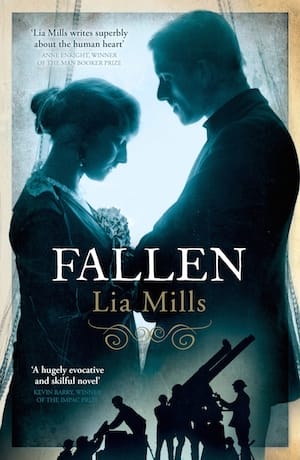

Chosen as this year’s One City, One Book selection for both Dublin and Belfast, this novel follows everywoman Katie and her everyman twin brother Liam through the Rising.

“If we lose our memory, how do we know who we are?”

This is the rhetoric put to Fallen’s narrator, Katie Crilly, as she embarks on a project documenting the history and meaning of Dublin’s monuments in the year 1914.

Lia Mills’ 1916-centenary book follows Katie through her next two years of early adulthood as her twin brother sets off to war, leaving her to become a bewildered witness of the Rising.

Fallen was the chosen book for this year’s One City One Book festival – an event held every April, aimed at encouraging us, the public, to read the promoted book and engage with themed activities held in Dublin city.

This year, explains director of Dublin UNESCO City of Literature Jane Alger, the festival partnered with Libraries Northern Ireland, “in honour of the 1916/2016 commemorations”, to become Two Cities One Book.

Amongst the funding bodies were UNESCO, Dublin City Council and the Department of Foreign Affairs’ Peace and Reconciliation Fund. What kind of 1916 commemorations can these bodies openly “honour”? Recent European events have rendered ludicrous all glorification of the lethal relationship between sacrifice and religiously sanctioned political violence.

If the 1916 Rising is the pivotal moment by which the republic is to know itself, what kind of memory should we make of it? Much as we may cherish Irish independence, the terms of our pride must today negotiate with a more complex narrative than the messianic, single-minded versions once taught in our classrooms.

Amidst Ireland’s 1916 commemorations, Irish Times articles by Mary Condren and Patsy Mac Garry, along with the child-victim profiles and Francis Sheehy-Skeffington’s 1915 open letter, called for the currency of blood sacrifice to be scrutinised. For the London Review of Books, Colm Tóibín provided an unflinching analysis of the personalities of the time, using the writings of Yeats, Joyce and Pearse, and avoiding any exaltation of the ideologies at play.

Amongst The Stinging Fly’s collection of Rising-themed writings, was a contribution from young poet, Aisling Fahey, about the collateral death of a two-year-old: “Whose job was it to peel her body off the pavement?/Did they have to peel the mother from her fading figure first?”

It is in this spirit that the book chosen for the centenary One Book Two Cities event is narrated by a character who is neither Anglophobic nor imperialist. Katie is caught in the tangle of 1916 politics but remains as close to contemporary political correctness as possible.

Fallen opens within some well-oiled conventions – a fictional character positioned at a juncture of history, Katie is the child of some Bennett-like parents: an anti-feminist, superficial, hysterical mother; and a sensible, sensitive, supportive father.

The scope of the book does not stray too far from that of historical fiction written for the purpose of “bringing history alive” for readers. And there is a degree to which the One Book Two Cities event, and the general push behind Fallen, feels like parental pedagogy – here is something easy for the masses, to teach them a bit about our past . . .

But Fallen never claims to be a challenging read, and Lia Mills’ talent for creating an interior landscape, and identifying the subtle shifts that take place in the mind and body carry the story through with skillful elegance.

When she loses her twin, Katie’s “mind couldn’t fit itself around the shape of his absence”, and watching her brother’s lover with a child, she is struck by a sudden revelation: “In that moment I saw that she’d meet someone, marry, have children. But the children would not be Liam’s. It was as though she’d tugged a plug lose in my chest.”

The book has been carefully researched, and contains a number of cameos and references to famous figures of the time – Bennet, Kettle, the Sheehy-Skeffingtons, Yeats, Connolly, with a noble effort to include important members of the feminist movement: “No one worked harder than Mary (Hayden) to bring that about for women.”

Yet it is peopled with so many stock characters – Annie the pimpled maid-with-a-man-in-the-kitchen, Nan and Lockie, the affectionate, plain and dutiful housekeepers who know (and seem to relish) their place in society, the drunken nursemaid, the angelic sickly sister – that at times the scenes lack the depth to be engaging.

Mills’ keen eye for the tiny details and moments that comprise experience, make the second half of the book the most engaging: “It was the first time I’d heard my name from his mouth. It felt like a touch . . . I gathered my own clothes and got dressed. Every hook and eye sealed the rich, strange smell of him against my skin.”

Katie’s sexual awakening coincides with the height of the rising, and the title is a play on the double meaning of the fallen women of Catholic Ireland and the fallen men of war. It’s a great idea – conjuring all the sexualised bloodiness of martyrdom and notions of female purity that were inwrought with the nationalist ideology of the time.

The Crilly twins “fall” in starkly contrasting ways, but, by the title’s implication, the death-fall of the male and the sex-fall of the female twin, might be two sides of the same coin. It is a pity that the metaphor was not drawn out further in the novel itself, where Katie’s experience, though beautifully and convincingly written, reads more like an appendix to the action of the book, with no real attempt to interrogate the ideological relationship between sex and death in 1916 Ireland.

Katie is, by her own admission, “very dull”, but she serves as a half-understanding witness to the mess of violence surrounding her. Through her lover and her brother, we hear despatches of World War I, and while they may not add much to a body of war writing, they are certainly engaging, convincing, and moving accounts.

Katie reflects: “Every one of them someone’s brother, son, father, loving and loved, trying to kill men just like themselves.” These are, of course, the kind of laments so often made, but when dealing with a phenomenon as time-old as war, creating a description that is both original and authentic can only be a next-to-impossible task.

In any case, Katie makes no claims to be a singular or complex thinker. Her function in the story is rather to play Everywoman to her absent brother’s Everyman – each the plaything of history. Through her eyes we see the suffering of the injured in 1916, hear the justification for the Rising, and experience the shock of the locals as well as the cruelty of some of the British soldiers.

Katie begins a job as a historical researcher, and this occupation encourages her to reflect on Dublin’s monuments, geography and history in detail:

“Narrower streets stretched off to the left and right of me, leading through the markets and past smaller, meaner shops to the tenements. Women in shawls and full skirts who sold fruit and potatoes from barrels were already setting out their wares . . . Crossing the river, I glanced upstream at the Ha’penny Bridge, which would have been replaced by the Lutyens Gallery, if we’d had the money to build it . . . ’

Although Katie’s unusual attention to the layout of her city can be explained, and the historical detail is often interesting, their incorporation into her narrative often feels a little contrived.

Fallen shies away from the soapbox, concentrating instead on the pedestrian experience of political conflict.

The prose is sometimes a little repetitive – there are a lot of thoughts echoing in “hollow chambers”, noise and crowds tend to “boil” and too much of the light is “pearled”, but there are also some lovely single-use descriptions: “the crown of Dad’s head glowed, like the fragile shell of a burnished egg”.

At its best, Mills’ writing is insightful and haunting. “Overhead”, observes Katie, “the clouds were the colour of bone.”

This book fitted the Two Cities One Book festival comfortably, and it is a welcome addition to an increasingly considered approach to Irish identity.

Fallen by Lia Mills (Dublin: Penguin Ireland, 2016)