What’s the best way to tell area residents about plans for a new asylum shelter nearby?

The government should tell communities directly about plans for new asylum shelters, some activists and politicians say.

Some argue that Iveagh Gardens should remain cloistered and quiet. Others say that making it more accessible would benefit Dubliners and restore it to the original vision.

They met at the Iveagh Gardens in the early afternoon, pushing through the holly bushes and undergrowth to a patch of land by the tall boundary wall.

Pom Boyd started the campaign last week. It was a couple of days after she heard of plans to knock down part of the old wall that divides the gardens from the National Concert Hall.

For those who live in the south inner city, the gardens are one of the few secluded open spaces that they have, she said on Saturday. “The point is, this is unique,” Boyd says.

They put up signs on trees: “Save the Iveagh Gardens”. Or laid them on the leaves on the ground.

“We would have called it the Secret Garden,” said another of the protestors, Tina Robinson. For her and her children, the walls surrounding it make it a special place, one to be discovered.

Robinson, like others, was unsure of the details of the planned changes. “But I don’t think it’s a good idea to open this up,” she said, pointing towards the giant wall.

The Office of Public Works got permission for the development on the other side of the wall more than a year ago from Dublin City Council.

The plans show the refurbishment of empty parts of the National Concert Hall and the real tennis building, to create a National Children’s Science Centre to host exhibits and interactive areas.

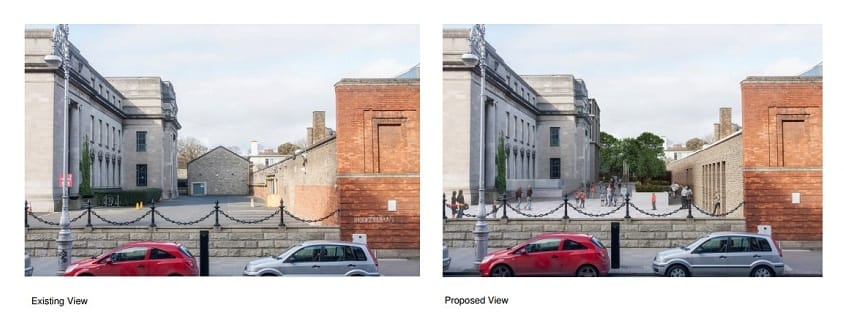

They also show a new four-storey extension with a planetarium dome to the west of the north wing, on the boundary with Iveagh Gardens.

To make room for this extension, the plans include demolishing an old workshop, maintenance shed, and part of the boundary wall along the Iveagh Gardens, “allowing for a new access ramp and steps into the Iveagh Gardens”.

When the plans were making their way through the planning process, there were a flurry of objections from around the world from real-tennis enthusiasts, who said that they wanted the court to come back into use. It would bring groups to the city for the tennis and “craic”, or even for good, said one.

The Irish Real Tennis Association appealed to An Bord Pleanála the council’s decision to grant permissionfor the changes. The board set some conditions, but approved the development. That was in September 2016.

Those who gathered on Saturday didn’t mention the old tennis court, though. They were more worried about the removal of part of the boundary wall, and how the gardens would be opened up.

There is a still a bit of confusion as to what is going where, said Dairne O’Sullivan, one of the earliest to arrive.

Regulars in the gardens, many of whom have dogs, said they didn’t really register what was going on at the earlier stage of the planning process.

So they missed the windows to make submissions to the planning process, which now makes opposition difficult.

“A challenge to the courts has to be lodged within weeks of the appeal decision. There is therefore no provision for challenging the decision at this stage,” said a spokesperson for Dublin City Council.

The Office of Public Works Press Office didn’t respond to queries about the timeline for the project, or protestors’ concerns.

In its planning report, the Office of Public Work pitches the design of the development as one that will reinvigorate Iveagh Gardens, and reconnect it with the National Concert Hall complex. That’s how it was when it was built.

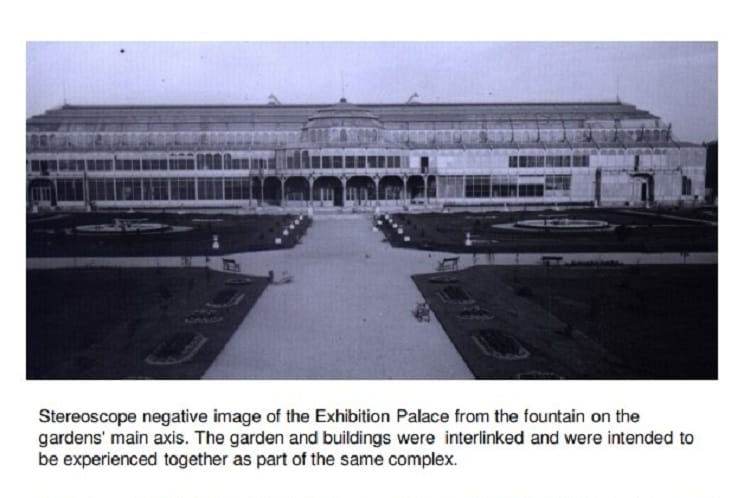

When the Dublin Exhibition Palace and a giant glass, enveloping Winter Garden were erected in the 1860s – long before the exhibition building became the concert hall – the landscaped gardens were part of the vision.

Sometime in the 1880s, though – after Sir Arthur Guinness and his brother Edward Cecil had bought back the buildings and site from the company that owned it, and the elegant Winter Garden was shipped off to London – the concert space was extended to the west and a new external wall was built.

In 1939, Iveagh House, the tennis court and the Iveagh Gardens grounds were granted by Rupert Guinness, the second Earl of Iveagh, as a gift to the state.

In its planning report, the Office of Public Works says that the idea is to create “a new conversation with the old building and a re-connection with an interrupted dialogue with Iveagh Gardens”.

There will be a new colonnaded space, where diners and exhibition visitors can sit on the terrace, and which is “transformed by the potential to make a more unified cohesive public realm bringing all the disparate elements together as a more legible and pleasurable civic experience than exists at present”.

The council’s conservation office okayed the plan, and said that the “demolition has been kept to a minimum”, and is needed to put in a new access ramp and steps into the gardens, and reconnect it to the building.

Labour Councillor Rebecca Moynihan, who is head of the council’s arts, culture and recreation committee, said she thinks that opening out the gardens to make them more accessible is a good move: “I think it’s really welcome. It’s lovely because it’s a hidden park, so to speak.”

The city centre lacks public green spaces, and by connecting the gardens to a big cultural institution, there will a greater sense of public ownership of both, she said.

More people will use the public space, but also realise “that the cultural institution belongs to them, as well”.

“Stephen’s Green is open at a number of entrances and it’s a really pleasant place to be, and a pleasant place to go,” she says.

“I really don’t think that you should limit access to public spaces, or people should think they can keep public spaces to themselves.”

Many of those who went to the protest on Saturday had dogs in tow.

“It’s a really dog friendly park,” said Holly Robinson, who met O’Sullivan through walking the dogs, one sniffing another. Many of the park regulars met that way, she says.

The gardens are more enclosed than St Stephen’s Green, so she has less concern that the dogs are going to run out onto a main road, she said. A little puppy trails along one of the paths, dragging a loose blue lead behind it.

Boyd, the lead organiser, said she also walks her dog there every day. For those who are gardenless in the neighbourhood, this is the closest space that they have to that.

“This part of it would be gone completely,” she said, to a crowd in the copse that swelled to about 40 people and 14 dogs.

“Ten minutes away is Grafton Street, and here we are standing in a wood,” she said. “It’s unique.”

“This is too important to me not to do something about it,” she said. But it’s unclear, as yet, what the next step is.

Others also spoke up from the crowd. “I’m thinking of tying myself to a railing,” said Patricia Hurl, with a sign around her neck that read: “For Dog’s sake, save our park”.

The wall is an old artefact, too, said Sean Miller. “They’re talking about knocking the wall as if it’s nothing.”