What’s the best way to tell area residents about plans for a new asylum shelter nearby?

The government should tell communities directly about plans for new asylum shelters, some activists and politicians say.

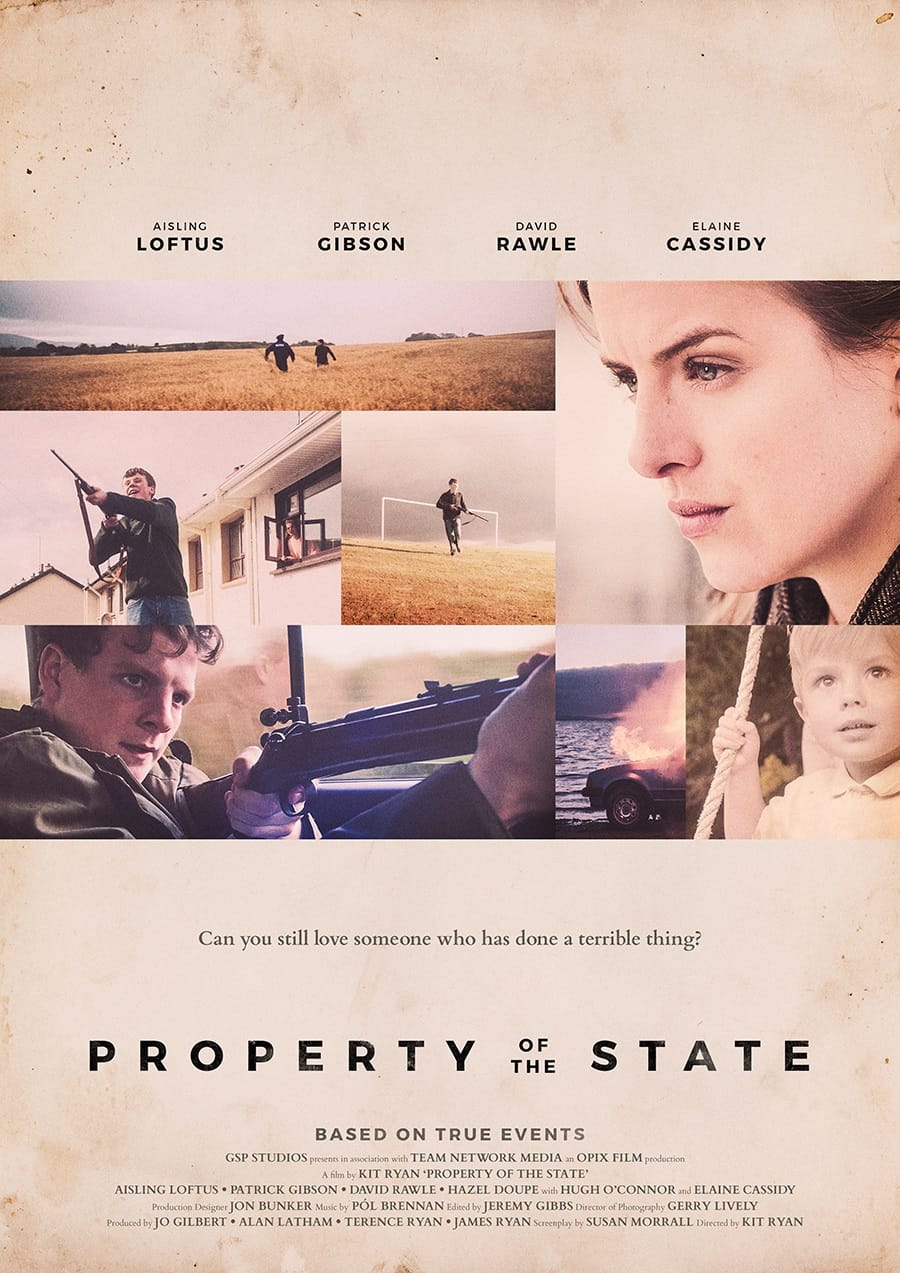

Mixing the social-problem and horror genres, this new film explores one of Ireland’s most notorious murder cases, and its effects on those it left behind.

Property of the State explores one of Ireland’s most notorious murder cases, and its effects on those it left behind.

We open with tranquility, a riverbed distorted by the gentle shimmering of water. This calming scene is soon disrupted by footsteps, as two figures move at pace through the water. They’re shot out of focus. One of them appears to be carrying a gun.

We will not see the full picture or grasp the significance of this sequence until later in the film.

The contrast between these barely visible soft-focus individuals and the clarity of the nature photography, captured as it is, with perfect focus, foregrounds a running tension in Property of the State: the blurry line between truth and fiction and the difficulty in dramatizing a crime that still hangs in the Irish consciousness.

The film begins with Ann Marie O’Donnell (Aisling Loftus) traveling on a train with her young son. She is a pariah; the other passengers jeer and snipe at her before moving to another carriage. Ann Marie is her brother Brendan O’Donnell’s sister, and lives her life in the shadow of his actions.

Loftus provides voice-over narration that is based on real-life journal entries. A deft visual flourish brings us back to the past; as we enter a tunnel, Ann Marie’s reflection morphs to her younger self. Loftus’s narration guides us through Brendan and Ann Marie’s early life, presenting Brendan as a troubled child and his acting out as a direct result of nurture rather than nature.

The young Brendan is a needy child. He has an extreme bond with his mother, who sits with him at school. His closeness to and reliance on his mother leads to friction with his father.

The O’Donnell patriarch is never shown to us head-on. He is filmed at angles or obscured by obstacles. We hear his fury and see the results of the beatings he doles out to Brendan and his mother, but he is for the most part a non-entity.

Brendan and Ann Marie’s father is less a man and more a violent force that terrorizes Brendan and, in the film, serves as the first of many harmful authority figures in his life.

Traditionally, social-problem films show figures of authority or institutions as ineffective and at the core of the issues explored within the film. Property of the State adheres to this formula, and shows the audience the many times that Brendan was allowed to slip through the cracks.

Early in the picture we see an aptitude for sport stifled by Brendan’s coach, a priest who sexually abuses him. Brendan leaves school and begins a cycle of anti-social behaviour.

At 13, we see him take shots at gardai with a hunting rifle. Later, in a juvenile detention centre, Brendan is raped by a prison officer. This sequence is one of the film’s most powerful.

An extreme close-up on Brendan’s face makes for extremely uncomfortable viewing. A swinging light bulb flickers on and off, punctuating this harrowing sequence with fleeting moments of respite.

Director Kit Ryan, who has previously worked on horror movies, brings some of the ambience of that genre into many sequences in this film. As the narrative progresses, similar techniques are turned on Brendan as his anti-social tendencies develop into dangerous intent.

Time and time again, we see the institutions and people that are supposed to protect Brendan from himself and others neglect their duties. In a psychiatric-care unit, we see Brendan smash the back of his head against a white wall until it is stained red with blood. The orderlies attending to Brendan take too long to intervene and he ends up in hospital.

Throughout these adolescent years we see Ann Marie growing up all too quickly. She has to forego youthful fun and romantic relationships, focusing instead on looking after her infant son and her troubled younger brother.

Property of the State’s casting is strong throughout, and attention to detail and convincing ageing of characters allows the film to move through time effortlessly. The gradual hardening of Brendan through his experience carries over from one actor to another, creating a continuity that is rarely pulled off as well as it is here.

As the narrative develops, our sympathy for Brendan is tested. He lashes out at Ann Marie and her baby in a sequence that’s certain to have many audience members covering their eyes in horror. For me, this was the turning point in the film’s narrative.

It’s at this point in the film that the narration begins to let up, and the events feel more speculative, with Loftus chiming in now and then to express regret. The film never really feels like it’s telling Ann Marie’s story, and perhaps this is an impossibility, as her life collides with Brendan again and again.

Patrick Gibson’s Brendan is chaos incarnate, much as his father was a signifier of violence. It’s harder to feel for Gibson’s older, violent Brendan than it is for Brendan the mistreated and misunderstood child, or Brendan the abused and troubled teenager.

Brendan as we see him in the latter part of the film is the result of the prior scenes of abuse and neglect. Although these sequences are put out of mind for the film’s nail-biting final act.

As the film draws to a close, Brendan’s actions become more extreme. He engages in a number of kidnappings at gunpoint. This eventually leads to the killing of a young mother and her son. Brendan also abducts and kills a young priest.

At gunpoint, Father Joe Walsh drives Brendan to a woodland. The camera cuts between Walsh glancing up at his rear-view mirror and Brendan sitting in the back of the car, gun in hand.

Brendan’s crazed look and the foreboding nature of the scene made me think of the final shots of Taxi Driver, when Robert De Niro gives Cybill Shepherd a look somewhere between love and menace. Brendan has that same look, as though he’s still a scared child living the only life he’s ever known, wanting something more, but never knowing what it is, or how to get it.

The film quite literally marches the audience toward its grim conclusion. Brendan’s trial and sentencing is shown as an injustice. Another final failing on the part of institutions that are supposed to help men like Brendan.

Ryan does attempt to bring the story back to Ann Marie, who struggles to get by and rebuild her life even years after her brother’s sentencing. The closing quotation taken from O’Donnell’s diary plays on Francis Xavier’s famous “give me the child” promise.

Property of the State is an admirable picture. The mingling of the social-problem and horror genres stops it from feeling typical. However, the promise of the film’s premise is never quite met: this is not Ann Marie’s story.

She serves as something of a bookend helping to stress the film’s core message, one that’s worthwhile even if it sometimes gets lost in the shuffle.