What’s happened with Manna’s plan to expand its drone delivery service across Dublin?

It still only has one base, in Dublin 15, with planning permission – and that’s due to expire this year.

The City Centre Crime Victim Survey was commissioned by Dublin Inquirer with fieldwork and data preparation carried out by Amarách Research

A new survey commissioned by Dublin Inquirer, with fieldwork and data preparation carried out by Amarách Research, offers insights into levels of crime in Dublin city centre.

This City Centre Crime Victim Survey includes responses from 600 people, aged 18 and over, who visit or live in the area.

Twelve percent of respondents (72) indicated that they’d fallen victim to some form of theft in the city centre in the 12 months up to September.

Meanwhile 9 percent (54) of people said that they had been threatened in a public place, and 3 percent (17) said that they had been threatened with a weapon.

Two percent (13) said that they had been “deliberately hit with fists or kicked”, and 1 percent (6) said that they had been injured with a weapon.

And 19 percent (116) said that they had been insulted or verbally abused while in a public place – such as the street, public transport, a bar or cafe.

The survey was carried out online over a week in September, and has a margin of error of 3.9 percent, according to Amarách.

Debate around rates of crime in Dublin city centre has heightened over the last five years – driving talk of “rejuvenation”, with changes in policy through the Dublin City Centre Taskforce, and high-visibility policing by Gardaí.

But there is little solid data to anchor debate.

There’s no evidence basis behind policy regarding safety in the city centre, says Gary Gannon, a Social Democrats TD and party spokesperson for justice. “It’s based on almost a humpty-dumpty approach.”

Something high-profile happens, Garda statistics are thrown about, but those aren’t that helpful, he says.

Police data has its limitations. Reported crimes are a better indicator of police activity than of crime rates, save for higher-harm crimes such as murder.

A 5 October press release from An Garda Siochana pointed to changes in trends in reported crimes as a result of its high-visibility policing initiative in the city, and targeted operations.

Thefts and robberies “from the person” are down by about 30 percent, and thefts from shops are up 6 percent, says the release – although which period this is compared to isn’t totally clear.

Crime victim surveys, meanwhile, are an attempt to capture rates not just of crimes that are reported to Gardaí, but also the “dark figures” of unreported crimes.

Although, crime victim surveys too have their limitations, such as a more narrow set of questions. For example, after consultation with academics and the Dublin Rape Crisis Centre, our survey omitted questions relating to sexual assault.

We hope to get the funding to repeat and improve this survey annually, which will start to build a picture of trends – and, over time, allow analysis of efforts to reduce crime in the city centre.

Comparing the figures from the Amarách survey with other data sources is tricky – because the geographical areas covered in different datasets can vary, as can time periods, and definitions of crimes.

The Central Statistics Office (CSO) has periodically carried out a thorough crime victimisation survey – but those figures are largely nationwide.

The most recent figures, from 2019, are also marked “under reservation” currently – although the CSO hasn’t yet answered queries sent on Monday as to why that is.

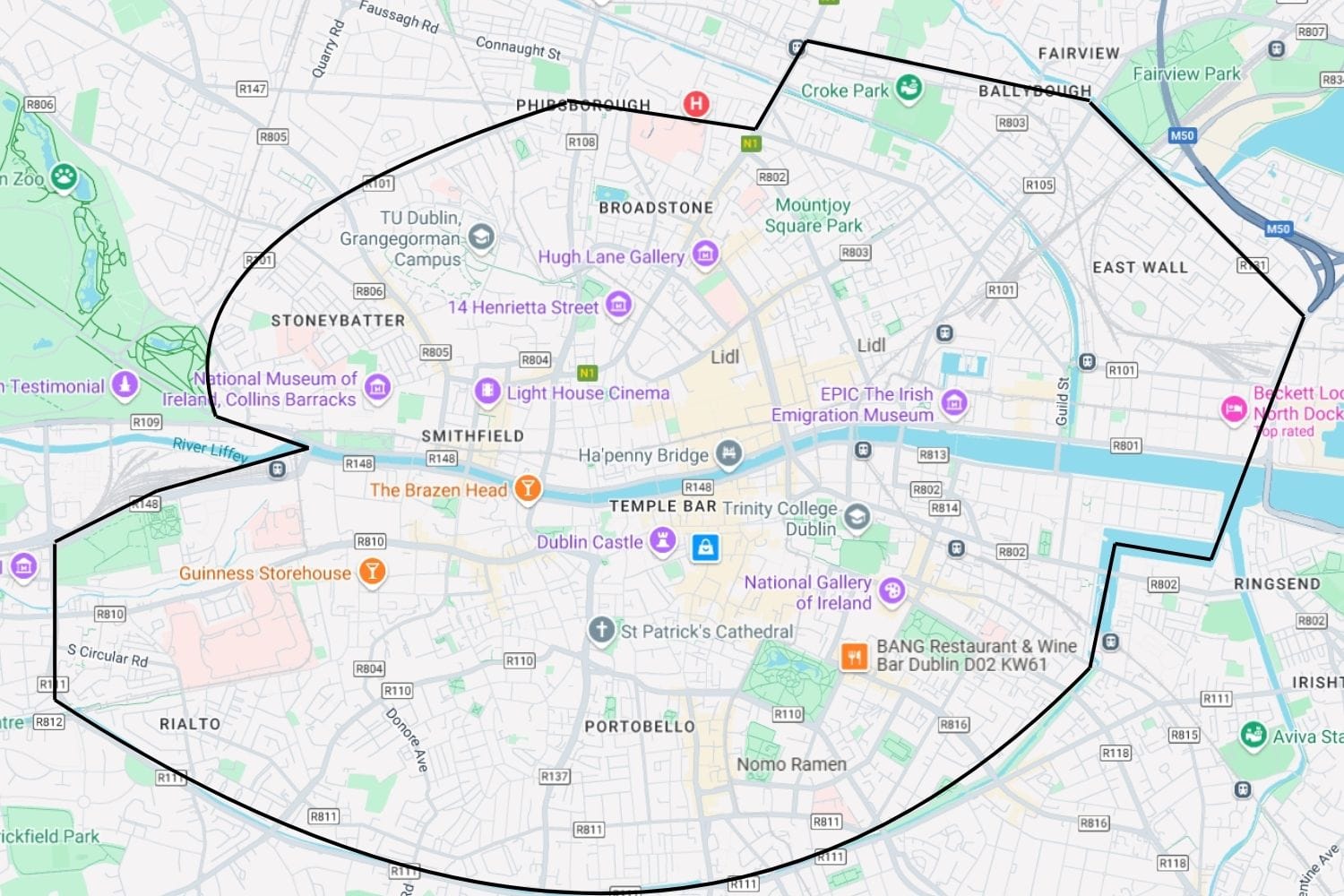

For our survey this year, Amarách showed respondents a map that defined Dublin city centre – after much debate in the Dublin Inquirer office – as roughly the area between the canals.

Six garda stations in the city have operational areas that largely, although not exactly, overlap with that area – Bridewell, Fitzgibbon Street, Kevin Street, Mountjoy, Pearse Street, and Store Street.

Neither the CSO, nor An Garda Síochána could provide exact population data for those Garda station areas, for those aged 18 years and over.

But small area data from the CSO’s 2022 national census suggests that the combined population, aged 20 years and over, of those areas is roughly 132,100.

Reported crime data for those six Garda stations for 2024 therefore suggest that the equivalent of 11 percent of residents 20 years old or older had been the victim of “theft and related offences”.

Meanwhile, 0.8 percent have been the victim of “burglary and related offences”, and 0.5 percent were victims of a robbery, extortion, or hijacking, that data shows.

Our survey’s headline figure for theft wasn’t that different – with 12 percent of adult respondents saying they had been subject to some kind of theft. But those figures were broken down further.

They show that the most commonly experienced types of theft were having something “stolen from your hands or pockets or bags”, and having a bicycle, electric bicycle, or electric scooter stolen.

Michele Puckhaber, chief executive of the Crime Victims Helpline, said that people may dismiss theft as small-fry.

“But what we hear on the helpline is that that can be a significant loss for someone,” she says.

A stolen bike or scooter can hinder somebody’s ability to get to their job, or school, she says. When it happens multiple times, it can leave people feeling very targeted, she says.

Meanwhile, CSO population and reported crime data suggests that the equivalent of 2.2 percent of the people in the area covered by the six Garda stations had reported “attempts/threats to murder, assaults, harassments and related offences” in 2024.

And the equivalent of 4.3 percent of the population reported “public order and other social code offences”, the data suggests.

That would include offences under Section 6 of the Public Order Act, which make it an offence “for any person in a public place to use or engage in any threatening, abusive or insulting words or behaviour with intent to provoke a breach of the peace or being reckless as to whether a breach of the peace may be occasioned”.

Those figures appear much lower than the – differently defined but with overlap – experiences of respondents to our City Centre Crime Victim Survey.

One thing that could help to explain this discrepancy between Garda crime data, and the survey results is that responses to follow-up questions in the survey suggest a low rate of reporting experiences of threat, assault and abuse to Gardaí – although breaking it down significantly complicates that analysis also.

Of those who reported being threatened, with or without a weapon, deliberately hit or kicked, or injured with a weapon, 30 percent (17) said that they reported it to Gardaí while 70 percent (41) said that they didn’t.

Cieran Perry, an independent councillor, said that the crime figures from the survey seem lower than he would have expected. But “perception versus reality is a known problem”, he says.

Just because a group of people may be hanging out on a corner, using drugs or even fighting over them, doesn’t mean that they’re dangerous for passersby, he says.

But it does look frightening to people, he says.

Young guys on scramblers and e-bikes flying up footpaths and all masked up is another complaint that he hears a lot, he says. “That gives a serious impression of lawlessness.”

It’s more of a risk too, he says. It’s an anecdote, he says, but he did hear from someone who had challenged a scooter kid, only to be pursued and threatened and chased into a pub.

“I think that might be a good example of where you might or might not see threats,” he says. Most people just get out of the way but those who challenge it do probably risk being threatened, he says.

Kourtney Kenny, a Sinn Féin councillor, said that to her, the survey figures also sound lower than she would have expected.

One serious issue that she hears regularly about from constituents, particularly living in some of the city centre flat complexes, is intimidation, she says.

In the survey, 1 percent (four people), when asked if they had been a victim of any crime outside of those asked about specifically, said that they had been subject to “intimidation”.

Also, as part of the survey, 80 respondents who live in Dublin city were asked how much of a problem is “intimidation or harassment or threatening behaviour” in their neighbourhood.

Seventy-eight percent of them (63) said that these were a serious problem or somewhat of a problem.

Kenny says that she knows of groups of neighbours transferring out of complexes because of intimidation.

Often, people don’t want to report this to Gardaí, she says. They’d prefer to report it to the council, their landlord.

But in questions to Dublin City Council, she was told that its system doesn’t allow for residents in social housing to report intimidation against them by residents in other social housing complexes, she says.

Efforts to deal with intimidation are slow, she says.

Gannon, the Social Democrats TD, says the figures for those who say they were threatened in the city centre in the 12 months in question stand out to him.

Public representatives often hear by email or in conversations how people feel the city is a threatening place, he says, but that’s something no figures capture as people are unlikely to report it.

But, “we are deliverers of anecdotes”, he says.

Says Gannon: “What we need are evidence-based policy responses operating across departments.”

That was supposed to be the Dublin City Centre Taskforce, he said. But now, he thinks that – as long as there’s no directly elected mayor – there should be a Minister for Urban Affairs responsible.

“Without that, we’re blowing against the wind here,” he says.

Note: If you’d like to explore the data, you can find an array of tables in this spreadsheet. We also have an SPSS file, get in touch if you’d like that: sam@dublininquirer.com.

Funded by the Local Democracy Reporting Scheme.