What’s the best way to tell area residents about plans for a new asylum shelter nearby?

The government should tell communities directly about plans for new asylum shelters, some activists and politicians say.

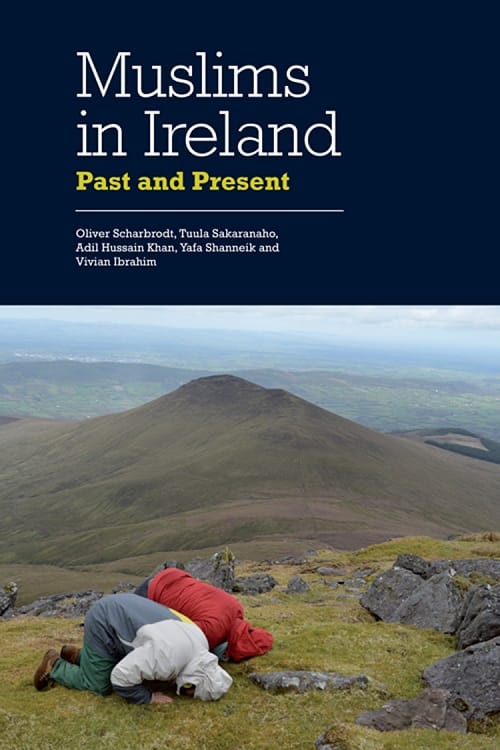

If you want to understand the complex identities, origins, and beliefs of Ireland’s Muslims, and their contributions to the country throughout history, start with this book.

There’s a good chance that someday a Muslim person is going to do something violent and horrible in Ireland. There are extremists among Ireland’s Muslims, just as there are extremists among every other group in the country, from Catholics to baristas.

Dublin imam Dr Umar al-Qadri told the Irish Times in July that when some of his fellow members of the Irish Muslim Peace and Integration Council (IMPIC) were passing out flyers at a mosque as part of an anti-ISIS protest, they were rebuked by three people who he quoted as having said, “We are ISIS, are you going to protest against us?”

They could have been teenagers messing around, or they could have been for real. Either way, al-Qadri seemed worried there are Muslim extremists in our midst, and the reports that several people have left here to go fight in Syria seem to support that.

We need to prepare ourselves for this future violent act by learning to see the so-called “Muslim community” in Ireland in all its diversity, and, in fact, as a constellation of communities from different countries, social classes and political backgrounds all lumped together because their faiths fit under the broad umbrella term “Islam”.

There is no person or organisation represents all of these people — neither your Sudanese doctor, nor your halal grocer, nor al-Qadri’s IMPIC, nor the Irish Council of Imams, nor your architect, nor your daughter’s school friend, nor the person who commits this eventual act of violence — any more than there is a person or organisation that represents all of Ireland’s Christians.

A good start to understanding the diversity of Muslims in Ireland would be reading Muslims in Ireland: Past and Present by Oliver Scharbrodt, Tuula Sakaranaho, Adil Hussain Khan, Yafa Shanneik and Vivian Ibrahim (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2015). If, that is, you can afford its £70 cover price. At 266 pages, that’s, like, €0.37 a page.

It begins at the beginning, going all the way back to the Sack of Baltimore by a group of “Turks” in 1631, and the donation of ships full food to Ireland during the Famine by the Ottoman Sultan Abdül-Mecid I, over in Istanbul.

It tells the stories of some of the colourful early arrivals, such as Mir Aulad, who moved from India to London and then to Dublin, where he was appointed to Trinity College in 1861. He was apparently “known as ‘The Mir’ in the cloisters of the university”, where he taught for decades.

Aulad was probably a Shia Muslim from what is now the Indian state of Uttar Pradesh. He joined the Society for the Preservation of the Irish Language, married an “Englishwoman”, and had his son Arthur baptised at the Church of Ireland in Rathmines.

In 1894, the “Araby” bazaar arrived in Dublin. It was some kind of fair or travelling market. The book tells us that, “While little can be said of the actual religion of [those involved], we know that Egyptians, ‘Moors’, Ottomans and Arabians were part of the bazaar.” And that in 1905, James Joyce included it in a short story called “Araby”, which was later published as part of his collection Dubliners.

In 1919, six Egyptian doctors arrived in Dublin “to take up training posts and medical positions” at Dublin hospitals including Rotunda, Coombe and Trinity. Five had names that indicated they were likely of Muslim origin (the fifth was, perhaps, a Coptic Christian, the book tells us).

Still, it wasn’t until the 1930s that the Irish Times began to carry reports of “Dublin’s first Muslims”. “These men, ‘30 or 40 of them in the Free State’, were all silk merchants”, it reported. In fact, Muslims in Ireland concludes, these were British subjects from Punjab, and “it is unclear whether all of the men were Muslim . . . some may have been Hindu”.

Soon, the government had noticed. In 1935, it brought in legislation accommodating halal (and kosher) slaughter practices. “We know that there was a thriving and substantial Jewish population in south Dublin, and it appears that early Muslim migrants may have settled in the same neighbourhood,” the book tells us.

I live on the edge of this neighbourhood, and, judging by the several halal shops and the Syrian, Palestinian, Lebanese and Indian/Pakistani restaurants, it seems like it still hosts a significant Muslim population, all these years later.

Although Muslims had been visiting Dublin for centuries, it wasn’t until after the Second World War that a “permanent presence of Muslims in Ireland” was established, according to Muslims in Ireland.

Apartheid in South Africa was the catalyst.

South Africa had (and has) a significant population of people of Indian ancestry, many of whom were transported there by the British as indentured labourers to work in the sugarcane plantations. Many of them were Muslim.

Under apartheid, they faced discrimination and restrictions on access to higher education. A political activist raised this issue with the Aga Khan, the spiritual head of the Ismaili Shia community, when he visited South Africa in 1945.

The Aga Khan, in turn, knew Eamon de Valera. Both were former presidents of the Assembly of the League of Nations. Soon, de Valera had secured a half-dozen places per year at University College Dublin (UCD) for South African medical students.

From 1952, the Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland (RCSI) also set aside a certain number of seats. By the 1960s, South Africans of Indian descent, some of whom were Muslim, formed one of the biggest contingents of foreign students at RCSI.

There are no official statistics on the number of Muslim people living in Ireland before the 1991 Census, when the government started counting.

But Muslims in Ireland cites the Islamic Foundation of Ireland as putting the count at about 300 in 1969. As more students — in medicine and various scientific and technical fields — came, graduated and stayed, these numbers grew.

This pattern persisted through the early 1990s.

With the economic boom came a surge in immigration, which brought “a massive increase in the Muslim population in Ireland, similar to the increase of other faith communities made up of immigrants such as Hindus, Buddhists, Pentecostals and Orthodox Christians.”

In the 1991 Census, 3,875 people identified themselves as Muslims. By 2002, this had increased to 19,147. By 2011, it had hit 49,204.

The new arrivals came from countries including Pakistan (6,662), Bangladesh (2,319), Nigeria (2,088), Sudan (1,470), Malaysia (1,373), Somalia (1,178), Iraq (1,081), Egypt (1,055), Algeria (1,047), Saudi Arabia (1,029), Turkey (1,029) and Bosnia and Kosovo (800).

Many were not the middle- and upper-class doctors and medical students Ireland was used to; they came from a broader range of backgrounds, and some were asylum seekers fleeing trouble at home. They were often lower skilled, lower paid, and some — while waiting for years for a decision on their asylum application — did not even have the right to work here.

Muslims in Ireland twice mentions members of the first wave of immigration complaining that members of this newer wave were ruining the reputations of Muslims in Ireland. “There is a sense that negative stereotypes and fears about the rise of radical Islam in Ireland are a result of the growing numbers of Muslim asylum seekers tarnishing the earlier positive image of Muslims in Ireland as a well-respected and integrated community,” it says.

Of course, not all the Muslims counted by the 2011 Census were immigrants. A large share of them were Irish: 37 percent (18,223) were citizens, most of whom (13,618) had been born here.

This is likely, the book suggests, to lead to “a trend similar to that seen in Western European countries with a more established Muslim presence: the appearance of a generation of Muslims not acquiescing to a position of marginality of migrants but claiming its place in Irish society.”

Of all the Muslims in Ireland, both immigrant and Irish-born, more than half (25,471) lived in Dublin at the time of the 2011 Census.

The next census is planned for 2016. It’s likely to report an even larger number of Muslims in Ireland, and in Dublin, and even more diversity.

Along with more Muslims have come variety of Muslim organisations, mosques and schools.

In Dublin, the first mosque was built at 7 Harrington Street. The Dublin Islamic Society bought the property in 1974, after having received a substantial grant from King Faisal of Saudi Arabia, according to Muslims in Ireland. In 1981, the government of Kuwait pledged financial support for a full-time imam. This mosque later moved over to South Circular Road.

In 1992, an Emirati medical student studying at RCSI approached the Maktoum family of the United Arab Emirates for support for a new, purpose-built mosque in Clonskeagh. The family had connections to Ireland; having invested “hundreds of millions of dollars in the international horse racing industry”, they own stables around County Kildare.

They agreed to support the project, and in 1996, Irish President Mary Robinson and the deputy ruler of Dubai, Sheikh Hamdan bin Rashid Al-Maktoum, inaugurated the Islamic Cultural Centre of Ireland (ICCI), also known as the Clonskeagh mosque.

Today, there are many more mosques: about 15 in Dublin alone, according to Muslims in Ireland.

There’s the mosque in Blackpitts Road, set up to cater to Pakistanis, who spoke Urdu, not Arabic, and “did not identify with Middle Eastern cultures”. There’s the Anwar e-Madina Mosque on Talbot Street, which also caters to South Asians, but has more of a Sufi bent. There’s the Clondalkin mosque, which serves largely Bangladeshi Muslims.

There’s the Al-Mustafa Islamic Centre in Blanchardstown, which caters to a multi-ethnic congregation including a contingent of Nigerians, and also has a “Sufi orientation”, the book tells us. There are mosques in Tallaght, East Wall and Coolmine that are frequented by Nigerians.

There’s the Ahlul-Bayt Islamic Centre in Milltown, which is the main centre for Shiis in Dublin. There’s also a small Ismaili community, and an Ahmadi community.

When the book was written, the Maktoum Foundation was financially supporting the Clonskeagh mosque and five others. It was also supporting meetings of the European Council for Fatwa and Research (ECFR), a Muslim Brotherhood-connected organisation based at the Clonskeagh mosque.

Amidst all the different mosques and all their ethnic and religious diversity, the Clonskeagh mosque and its leaders take a leading role.

They are connected with the Muslim Brotherhood, bankrolled by the Maktoum Foundation, and legitimised by the Irish government, which turns to them when it wants to communicate with Ireland’s “Muslim community”.

Sheikh Hussein Halawa, from Egypt, is the central figure in all this: he is imam of the Clonskeagh mosque, the chair of the Irish Council of Imams and the general secretary of the ECFR. You might have heard of him as the most prominent Muslim cleric in Ireland, but you might also have heard of him in connection with his son, Ibrahim.

Halawa’s son Ibrahim and three daughters were detained in Cairo during the demonstrations following the military coup of July 2013, which ousted Muslim Brotherhood-backed Egyptian President Mohamed Morsi. Halawa’s daughters were released after three months, but Ibrahim, an Irish citizen, has been held in Egypt now for more than two years without being charged.

Muslims in Ireland raises the question (gently) several times of whether Halawa and Clonskeagh should be the go-to voice of Muslims in Ireland — not because of the Muslim Brotherhood connection, but simply because they perhaps do not represent most Muslims in Ireland.

Many Muslims don’t go to services at all, and aren’t even affiliated with any particular mosque. Of those who do go to a mosque, most don’t go to Clonskeagh or follow Halawa.

So how does this Egyptian cleric come to represent so many Irish-born Muslims, Nigerian-born Muslims, Malaysian-born Muslims?

How does this specific Sunni cleric represent other strains of Sunnis, despite doctrinal differences — as well as Shiis, Ismailis and Ahmadis?

Perhaps the most important fault line among Muslims in Ireland is the yawning gap between the early, relatively affluent arrivals who are now doctors and engineers, and the newer arrivals, many of whom have been languishing in poverty in asylum centres for years, unable to work or even to cook their own meals.

If I were them I think I would be seething with rage. Or perhaps, if I had been waiting for enough years in limbo, I would be beyond that, and would have given up hope.

What is certain is this: “The children of a Muslim doctor who grew up in middle-class Milltown, in south Dublin, and who attend university and embark on a professional career develop a different rapport with Irish society from that developed by the children of asylum seekers who are confined to detention centres.”

And the doctor and her children might well be looking down on the asylum seeker and his children. As Muslims in Ireland notes about the results of interviews with several Muslim women from Sudan: “Some express their fear of the changing image of Sudanese people within Irish society as a result of the increasing influx of Sudanese asylum seekers.”

Perhaps the most fascinating part of Muslims in Ireland are the results of the personal interviews with Muslim women here in Ireland, like these Sudanese women mentioned above.

The author of the chapter containing these interviews, Yafa Shenneik, interviewed, for example, a group of Algerian women who, back in Algeria, had been part of the Islamic Salvation Front, known in French as the Front Islamique du Salut (FIS), and are now Irish citizens.

This organisation, Shenneik tells us, had been “established in the late 1980s as a reaction against the secular Francophone postcolonial elite”. After a civil war in the 1990s ended badly for their faction, “FIS activists were jailed or took refuge in European countries such as Ireland”.

Shenneik tells us that the “women blame the West for Algeria’s current socio-political and cultural situation, saying: “They [Europeans] destroyed our country, language, cultural and unity.” Perhaps not surprisingly, they do not seem eager to integrate.

Says one woman: “My children need to know that they are Arabs and Muslims. We are different. We are not Irish or Catholic.” If their children make friends at school with Catholic children, Shenneik tells us, they are told: “These are kuffar. It is as if you are making friendship[s] with the devil and you don’t want to be the devil’s friend, do you my dear?”

This is in stark contrast to the views Shenneik reports from women from Algerian, Libyan or Egyptian who are members or sympathisers of the Muslim Brotherhood. These, she says, “were from middle-class backgrounds and came to Ireland for educational purposes or to work as doctors, university lecturers, nurses or midwives.”

They reportedly see Ireland as a land of opportunity, and particularly appreciate that religion plays a major role in Irish society, which they see as making it a more comfortable place for them to live than a secular society where “people don’t fear God”. Although they want their children to learn about their Muslim heritage and traditions, they are quoted as saying “Catholics are very nice people”.

And then there were the Iraqi women, who were in an entirely different situation. “The majority of the Iraqi women interviewed were forced to leave their families, husbands or children, who were killed in Iraq, imprisoned or received as refugees in another country, and came to Ireland as migrants or refugees on their own,” the book tells us.

Some have since transferred their allegiance from the more traditional Grand Ayatollah Ali Al-Husayni Al-Sistani, to the Grand Ayatollah Sayyid Muhammad Husayn Fadlallah, whose views on gender roles are thought to be more progressive. Explains one woman: “Sistani’s views work well in Iraq when you have the community’s security but here in Ireland we are left alone. We need to be strong and independent.”

These are diverse views and experiences, but all of these women seem to have been Arabs. If Shenneikh had cast the net wider and brought us interviews from women who’d come from Nigeria, Malaysia, Pakistan, Bangladesh and further afield, we would have heard an even broader array of experiences and views.

Muslims in Ireland is perhaps the definitive work on the subject, and it’s filled with great historical anecdotes, like those about The Mir at Trinity, useful research on the histories of institutions, and illuminating interviews with individuals.

It is an academic book, though, and therefore not as accessible in terms of style and price as it could be. It’d be great to see a general-interest version of this book published, sold at a lower price, and distributed a bit more widely.

Everyone in our city could read it. And then, if, among all the violent crimes that happen in Ireland each year, one of them does one day happen to have been committed by a Muslim person, and if that person does shout something about ISIS along the way, we could all remember what we had read.

And we could remember that, on that day, there must be thousands of Irish Muslims baffled and outraged by what had happened, people with no connection to or sympathy with the evil idiot in question.