What’s the best way to tell area residents about plans for a new asylum shelter nearby?

The government should tell communities directly about plans for new asylum shelters, some activists and politicians say.

Ami Hope Jackson and Eileen Sealy have work at the College Lane Gallery in Howth, and a group show coming at Draiocht in Blanchardstown.

The College Lane Gallery lives inside a small white extension, part of the Old College Building on Main Street in Howth.

On a windy Tuesday afternoon, light though its shop-front windows hit a giant canvas on one of the walls, a work showing a pair of dead dogs, one with its abdomen sliced down the middle.

Artists Ami Hope Jackson and Eileen Sealy were sitting nearby, both wearing scarves and baggy jumpers.

The dogs were created by Sealy, and on the walls alongside were more canvases, big and small.

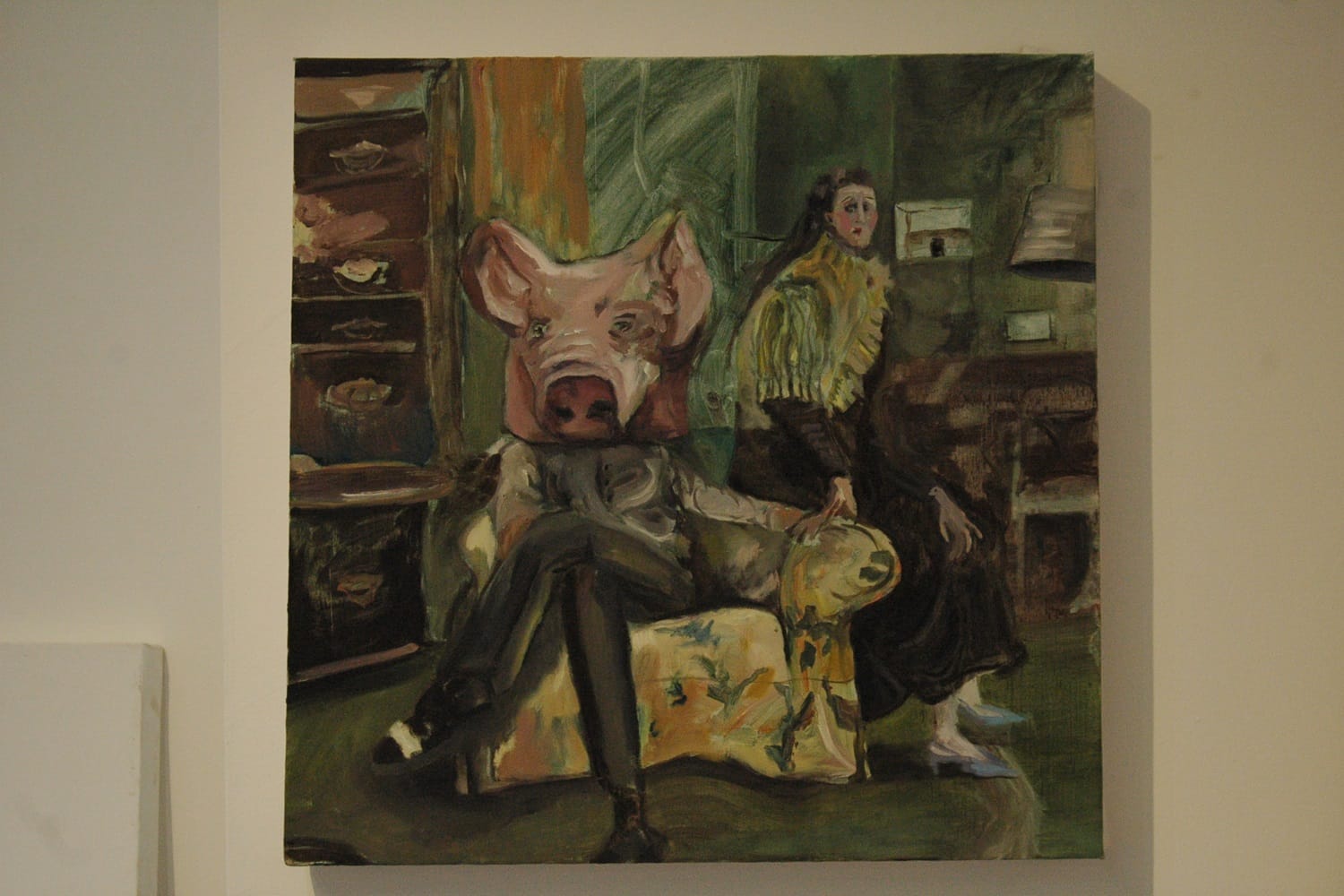

Among them, was a square portrait of a figure in an armchair, with the body of a besuited woman and the head of a pig. Beside the figure, a blonde woman leant against the armrest.

That was a piece that Jackson and Sealy painted together, while they are sharing a residency in the gallery, Sealy says. “It can be a fun thing, this intermingling of two painters, but also really irritating.”

“It’s the way friendships can end,” Jackson said, laughing.

As they speak, they are three days away from a group show, one involving both of them, in Draiocht, the arts venue in Blanchardstown.

They hadn’t submitted their works together, Jackson says, but their trajectories seem to be entwined. “It has always been a case of, let’s just go about doing what we’re doing. We share this parallel play, and then wait to see if a collaboration happens.”

“Like that,” she says, gesturing to the painting of the pig-person they worked on together. “Because usually it does.”

The duo grew up in Howth together, Jackson says.

Jackson moved to the peninsula at the age of nine from Nagoya, a port city in Japan, she says. “Coming from Japan to Howth had this culture shock, and in the middle of this I met Eileen, who was this weird local.”

It was 2007. They attended the same primary school, she says. “And right from the get go, we just started doing these little projects together.”

They loved to invent fictional characters, Sealy says. “We made this creature for the Chipper Fish, who became our mascot for years and years.”

“We made a big cloak out of chips,” she says.

The chips were sourced from the local Beshoff Bros takeaway, Jackson says. “We were obsessed with how seagulls attacked tourists coming and eating chips, and so we brought the cloak down to the pier and let the seagulls eat them off us.”

In 2018, Jackson moved to London to do a foundation year in art. Then, they both enrolled at the National College of Art and Design, she says. “Eileen was in paint, and I was in printmaking.”

Both would develop their own distinctive practices. But even after secondary school, they continued to collaborate, Sealy says. “Mostly it would be sculptural, or video or photography-based.”

One recent work, carrying on the seaside theme, was a short video of a staged picnic on a stoney-grey floating board in the sea.

While people swim around them, Jackson, Sealy and artist Faye Bronwyn Kinsella wade into the waters, fully clothed and covered in red and white face paint, to eat a lumpy cake with pink candles.

Their ideas always stemmed from conversations egging each other on, Sealy says. “You allow yourself to get carried away until the logical conclusion is sheer madness.”

On Tuesday afternoon, by a small staircase leading into the Old College, Jackson sat in a chair with red upholstered cushions and wooden armrests facing the windows.

Sealy was perched a couple of strides away inside the front window, next to several torn strips of paper, with biro sketches.

The works around the room diverged in style, but shared somehow a dark atmospheric sensibility.

Jackson’s pieces were mostly abstractions – with collage, and borrowings from both Irish and Japanese mythology, she says. “I’m looking at Celtic knots a lot, and trees and roots, very fluid forms.”

“And I feel like there is an overlap in the work with Japanese woodblock prints and calligraphy,” she says.

One work, hanging in the window, resembles flowers made from muddy green and pale blues, painted into a canvas with heavy brushstrokes.

Fixed to the leaves blooming from a stem is a small yellowing square of newspaper. It shows the lower portion of a man’s face, which she clipped from a Japanese newspaper.

Another shows a brown horse-type figure galloping away from a pinkish-grey nebulous creature, partially defined by swooshing black lines.

Jackson used artificial intelligence to generate a reference image that was eventually captured on canvas, she says. “It’s familiar and uncanny.”

Sealy’s practice, meanwhile, leans more towards the figurative, toeing a line between surrealism and realism.

Ferns grow from beneath the mattress of a woman’s bed. Children’s television icon Dustin the Turkey is given a human body, which he towels off in a bathroom.

In College Lane, her work has focused on her recent study of burial rituals, she says. “This was off the back of having worked in natural burial grounds in the Netherlands.”

She took up an artist’s residency in Groningen in the Netherlands, which involved studying natural cemeteries in forests, she says.

“Then in August, I left for Sulawesi in Indonesia where I went to research burial customs, and how different cultures deal with grief and mourning,” she says.

She looks up, at a Francis Bacon-esque image of deceased dogs lying supine with their teeth bared.

The painting of the dogs can be unpleasant to see, she says.“It is a meditation on something that can be uncomfortable.”

Another work in progress shows a burial that she photographed in Sulawesi. There, she says, people don’t typically bury loved ones.

The bodies are placed in a crypt, which is then opened every few years, she says. “They unwrap the bodies and leave them in the sun, like a social ritual,” she says.

There is a feeling of isolation in Howth that informs the work both of them do, Sealy says. “The entrance to the island is one Dart line, so there is this feeling of seclusion that is spooky and foggy, and it all feels like a weird theatre set here some days.”

“So that’s always been the backdrop for any weird project we’ve done,” Jackson says.

As Sealy and Jackson enter their second week of their residency in College Lane, their next outing is set for the Draíocht arts centre in Blanchardstown.

Organised by the artist collective Shell/Ter, the show, titled “The ladder is always there”, runs from 8 December to 3 February.

Featuring the five founding members of Shell/Ter and 10 emerging artists, the exhibition focuses on the collective’s role as a shelter for supporting those who are early in their careers, says Sharon Murphy of Shell/Ter. “We are looking at this idea from an emotional, psychological and philosophical perspective.”

“But also, we are looking at what it is from the point of view of an emerging artist,” Murphy says.

The show was one instance in which Jackson and Sealy didn’t knowingly join forces, Jackson says. “We both applied. But we were both really scared to tell the other if we had gotten in.”

Jackson’s entries, titled “bighug” and “bubble” are a pair of almost oceanic abstract works. Once again, they contain subtle collages clipped from Japanese newspapers, which are obscured beneath waves of greyish green, viridian and white paint.

Her colour palette is almost muted, says Murphy. “There is a quietness and confidence with white.

Sealy’s works are a self-portrait in a derelict bedroom, and a diptych of tin cans containing peaches and a fruit salad from the 1970s.

She found them in an abandoned hotel in Donegal, she says. “One looked beautiful and fruity, kitschy and frightening, and the other was completely dilapidated.”

“There’s something just hilariously enticing about tin cans, forever preserving the grimmest foods,” she says.

Jackson says it’s nice to be in a space now where they are working on distinct and separate ideas, because inevitably they always come back around to collaborating in some shape or form. “It’s how we approached this residency.”

She looks up at the portrait of the anthropomorphic pig and the woman, which bridges the gap between their styles.

Generally, their work visually, Sealy says. But what they share is an attitude, cultivated by their surroundings. “We both make from the same place.”