Look at converting some social homes in city-centre flats into cost-rentals, says Taoiseach’s group

No decision has been made on whether that will happen, a Dublin City Council spokesperson has said. But it hasn’t been ruled out.

The current development plan sets an aim of doubling allotments, caveated, with “if feasibly possible”.

Steve Rawson had waited 10 years before he finally, in 2021, got his hands into the dirt of his own allotment, his own plot in St Anne’s Park in Raheny.

Now, Rawson is the chair of St Anne’s Allotment and heavily involved in a vibrant community that has grown from the garden, alongside the carrots and cabbages, he said by phone on Tuesday.

It’s the tremendous spirit of meitheal and the regular social and fundraising events that Rawson really loves, he says. “Say if a member is ill, we'll come together and look after the plot for them until they overcome their illness, or whatever it might be.”

Some of the allotment has been reworked as a community garden, a larger shared space for growing rather than a plot for an individual to work on alone.

Now, more groups can get involved, he says.

There’s ecological benefits to allotment and community gardening too, says Aaron Foley of Dublin Community Growers.

So much of Ireland’s food supply is imported, leaving the country vulnerable to food insecurity, said Foley. “The community growing movement came about because people started to get really worried about this.”

Indeed, Dublin City Council’s current development plan seems to recognise these benefits, committing the city to supporting urban farming – and even sets a goal of doubling the provision of allotments in the city.

It’s unclear how much progress has been made on that, though. Dublin City Council hasn’t responded to queries about that sent on Wednesday morning.

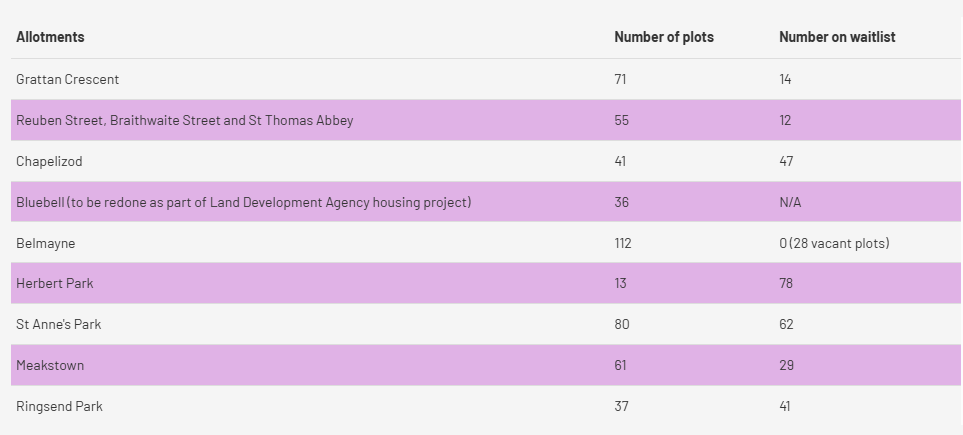

Demand for Dublin’s allotments remains high, show official figures. Just one city council allotment in Belmayne doesn’t have a waiting list and has vacant plots.

An allotment becoming available to someone waiting for one depends on an existing plot holder giving theirs up, a council spokesperson said by email on 8 July.

In other words, it is one in, one out. But few surrender their allotments each year, they said.

Allotments in the city are managed by either the council’s Parks, Biodiversity & Landscape Services section, or its area offices.

The longest wait list is for Herbert Park, where there are 13 allotments and a waiting list of 78 applicants.

There are 62 people waiting for one of the 80 allotment spots in St Anne’s Park – where Rawson managed to score one four years ago.

In Chapelizod, there are 41 allotments, with 47 on the waiting list. That waiting list is currently closed to new applicants – so demand could be even higher.

Donal McCormack, co-chair of Community Gardens Ireland (CGI), says the way that councils handle wait lists makes it difficult to actually gauge demand.

There is currently no legal requirement for local authorities to keep waiting lists for allotments or community growing spaces, he says. So, there’s no reliable data available on demand and for future planning.

Many local authorities have closed their waiting lists entirely, he says.

Others cap them, like Fingal County Council – which manages 900 allotments across four sites – and limits its waiting lists to 100 people.

In February 2024, McCormack says that Pippa Hackett, then a Green Party TD and Minister for Agriculture, Food and the Marine, issued a survey to all local authorities, asking for the numbers of community gardens and allotments.

Only 16 of 31 local authorities responded to the survey, McCormack says. None of the Dublin councils did.

In May, CGI wrote to Minister for Housing, Local Government and Heritage James Browne calling for the survey to be reissued to local authorities.

“We have yet to receive any response from the Minister to our request,” says McCormack.

A previous survey issued in 2018, he says, found that there were only about 2,500 allotments and community gardens in Ireland.

Meanwhile, in England, the Small Holdings and Allotments Act 1908 provides that if six people petition for a growing space, one must be provided.

That is, if the council does not already provide any allotments within its boundaries, says Tyler Harris, a legal adviser for England’s National Allotment Society (NAS).

If there is already a site, the council considers whether demand is significant enough to add another, he said.

“It would not be enough that there are simply six more people making a request for a plot than there are total plots in the council’s area,” Harris said, by email on Tuesday.

But to help measure demand, the NAS does recommend having 20 plots per 1,000 households, he says.

There were 225,685 private households in the Dublin City Council area at the 2022 census, according to the Central Statistics Office. So that would mean, following the NAS’s recommendation, there should be 4,500 plots in the city.

Catherine Bromhead lives equidistant between the Grattan Crescent and Chapelizod allotment sites. She has applied to join both waiting lists, she says.

Plots are available in Belmayne, an hour or more away by bus, according to Google Maps. But it wouldn’t suit her to travel such a distance by bus to garden, she says.

Better would be to have more, smaller sites scattered across the city, she says.

“We have all these derelict sites or fields that are just not being used for anything, and it just feels like, why can't we use them for something like an allotment?” Bromhead says.

That idea is, actually, an objective in the Dublin City Development plan 2022–2028.

The council aims to “support the provision of urban farming and food production initiatives, where feasible”, it says.

“And in particular, on the roofs of buildings, as temporary uses on vacant, under-utilised or derelict sites in the city and in peripheral urban areas / near M50, and in residential developments,” says the plan.

Other objectives, it states, are “to commit to increase the provision of allotments in the city by at least 100% if feasibly possible”, and to “carry out a survey of underutilised open spaces for community gardens with a view to identifying areas in the city appropriate and suitable for community gardens”.

Dublin City Council hasn’t responded to queries sent Wednesday morning asking how many meanwhile-use sites are currently earmarked for allotments, what plans are to meet the expansion target, and whether it has surveyed open spaces.

It was awareness of high demand that led allotment holders in St Anne’s Park to cede some of their plots to make a more accessible community garden, says Rawson.

There used to be 90 allotment plots in St Anne’s, but now there are 80, he said.

Members felt it was the right move, though, he says. Other local groups can now also enjoy the amenity – like the Central Remedial Clinic (CRC), Suaimhneas, the local mental health service, and the St Anne’s City Farm.

McCormack says there remains great confusion surrounding legislation for such spaces and the roles of councils.

Some local authorities have been quoting laws long after they were repealed, he says.

Still, Section 48 of the recent Planning and Development Act 2024 does offer a definition of community gardens that was not in previous legislation which, McCormack says, is a good step forward.

But, he says, there needs to be a strategy that each local authority has to build towards sustainable communities – and allotments and community gardens must be part of that.

He points to Scotland’s example.

There the government recently improved the guidance and laws around community growing, he says.

Councils now have to keep a waiting list and have a duty to provide sufficient allotments to keep that list at no more than half of the authority's current number of allotments, he says.

Funded by the Local Democracy Reporting Scheme.