What’s the best way to tell area residents about plans for a new asylum shelter nearby?

The government should tell communities directly about plans for new asylum shelters, some activists and politicians say.

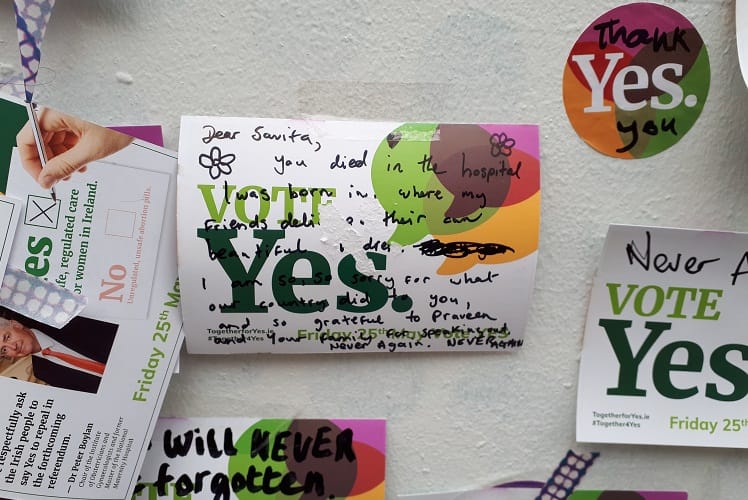

The speedy reaction by Dublin City Archives to collect messages left at the memorial to Savita Halappanavar in the south inner-city shows a new effort to value items from the here and now.

As the notes and tributes spread across the wall alongside the Savita Halappanavar mural on South Richmond Street recently, some librarians realised they were pieces of history that needed to be kept.

“We recognised that the cards and their content were within our collection policies […] worthy of permanent preservation,” said Acting City Librarian Brendan Teeling, by email.

The idea that museums and libraries should recognise objects of historical significance and grab them in the now – known as “rapid-response collecting” – has been catching on here, and overseas.

It’s a newish idea, says Emily Mark-Fitzgerald, an associate professor in the School of Art History and Cultural Policy at University College Dublin (UCD).

But it “would certainly be exciting to see in our museums”, she says.

Rapid-response collecting is an approach that the Victoria and Albert Museum in London has been taking for some time.

The focus there is on how designed objects enable us to understand the world we live in, says Corinna Gardner, senior curator at the museum’s Design, Architecture and Digital Department.

“It’s those objects that we seek to bring into the museum at the time when they are the subject of public and popular conversational debate,” she says.

Gardner and a colleague started with “a modest display” in 2013 to test what people thought of rapid-response collection. They’ve now got 30 objects that way.

One is a pink, knitted Pussyhat, widely worn at the women’s march in Washington DC in January 2017, following the inauguration of Donald Trump as president. That came from one of the founders of the Pussyhat Project, she says.

They’ve also got a virtual-reality Oculus Rift headset, developed by a division of Facebook, Inc. And KONE UltraRope, made with lightweight carbon-fibre, which has transformed how elevators operate.

Another acquisition is the mobile-phone game Flappy Bird, which developer Dong Nguyen removed from app stores after it took off. “The consequences from the addiction of the game became too much for him,” says Gardner.

While the V&A’s focus is on design, it doesn’t have to be, says Gardner. “As an approach, [rapid-response collecting] does translate and, I think, does have opportunity to work with social and historical change,” she says.

It works best if an object “enables us to ask difficult questions”, says Gardner. Her department sought objects around the Scottish independence referendum in 2014 and the Brexit vote in 2016.

The collecting should be democratic, too, says Gardner. She and her colleagues put out lots of public call-outs.

For recording Brexit, they settled on a Leave campaign booklet that adopted similar graphics to an official NHS handbook. “So that is where design is enacting our contemporary reality,” she says.

Gardner recently spoke about rapid-response collection at the Irish Museums Association’s annual conference.

Her talk was well received, says Mark-Fitzgerald of University College Dublin, who is a co-director at the association. “Lots of conversation provoked afterwards.”

Dublin City Archives began to collect material about the 8th Amendment referendum from both sides last week, prompted by the messages stuck alongside the Savita Halappanavar mural.

Council libraries were also worried that items might be lost or destroyed. So Teeling, the acting city librarian, commissioned a photography project to capture the content.

“Our overarching aim is to ensure that the images are accessible not just in the immediate future but also in 100 years’ time,” said Teeling.

The National Library of Ireland has also started to archive websites and other online material about elections and referenda, said a spokesperson by email.

That includes tweets, YouTube videos, and websites. Archivists are already working to collect leaflets and flyers, as well as newspapers, they said.

It’s too soon to say which Irish museums might pick up on rapid-response collecting, says Mark-Fitzgerald. “But it’s an easily adoptable and scaleable approach.”

The Little Museum of Dublin is a good example of “an indie that rapidly develops exhibitions of contemporary interest”, she says.

Trevor White, director of the Little Museum of Dublin, says curators there think hard about how to collect and display contemporary items, too.

It has Brian O’Driscoll’s rugby jersey from 2009 when Ireland won the Grand Slam, and a 2015 marriage-equality badge. That last item was donated.

They asked for objects, says Labour Senator Aodhán Ó Riordáin. “So I gave them my pin.”

Ó Riordáin says he has noticed a push among the public to collect the contemporary and preserve the present. “It is very important this week when we’re dumping all the posters.”

When he asked on Twitter whether anyone wanted referendum posters, he was “swamped with people from all over the world who wanted a YES poster”, he says.