What’s the best way to tell area residents about plans for a new asylum shelter nearby?

The government should tell communities directly about plans for new asylum shelters, some activists and politicians say.

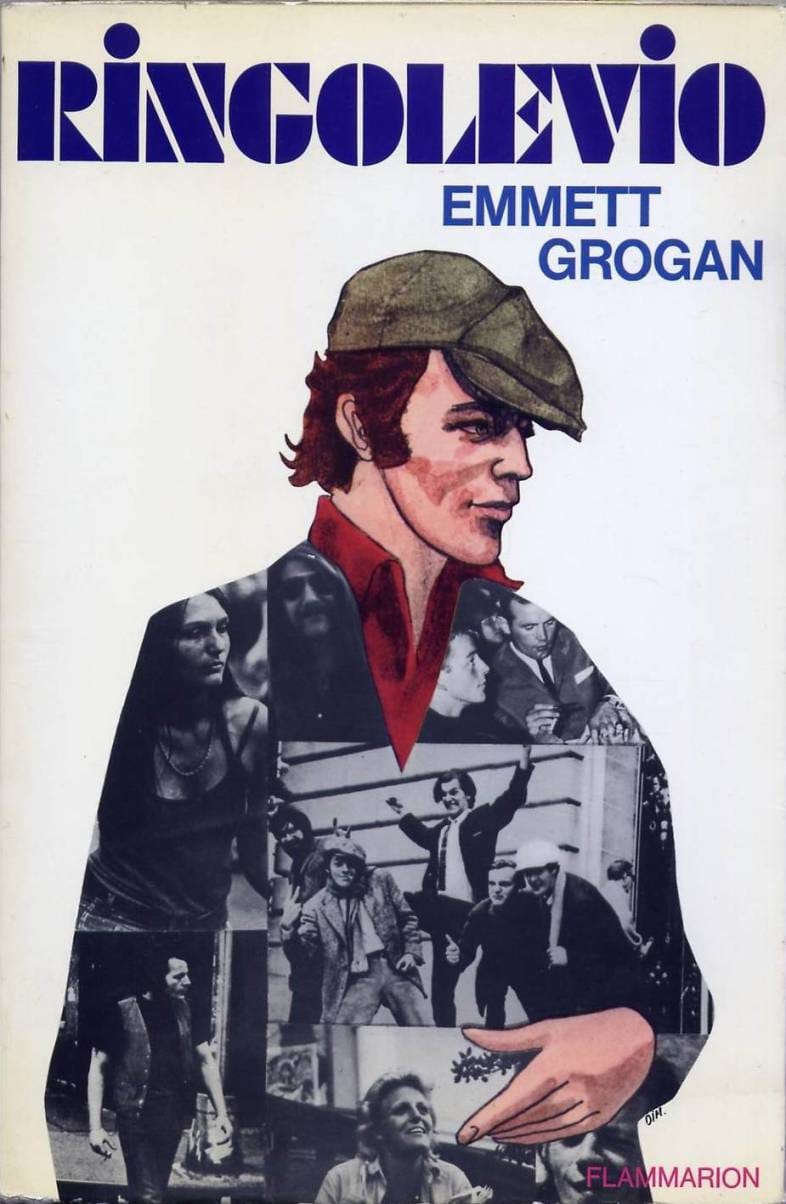

In his monthly column, Donal Fallon of “Come Here to Me!” takes a look at the life of Emmett Grogan, Irish American wild child and original hippy, who visited Dublin in the 1960s.

Emmett Grogan was a lot of things. One of the leading figures of the hippy movement that exploded in the United States in the sixties, he was an Irish American wild child from Brooklyn who rejected any kind of conformity.

He was central to setting up a free-spirited political society known as The Diggers, who were at the heart of the San Francisco scene of the 1960s. Grogan sang on Bob Dylan’s Mr Tambourine Man and knocked around with bands like The Grateful Dead, but he never let the facts get in the way of a good story.

There are more questions than answers around his life, even now. His memoir, Ringolevio, includes some fascinating insights on the Dublin of the 1960s, though if they should be believed is another matter entirely.

Writing about Emmett Grogan, Ian McGillis noted that “in 1978, when Bob Dylan dedicated his Street Legal album to the late Emmett Grogan, it was more than just a salute from a counterculture icon to a far less famous fellow traveller. It was one master of self-reinvention recognizing another.”

Given his clear influence on Dylan and others, it is remarkable just how little is known about the origins of Grogan.

He was born Eugene Grogan in November 1942, and his contemporary Peter Coyote remembered that “as the son of a clerk who served wealthy clients, Emmett felt consigned to an obscure future, to viewing wealth and power from the wrong side of the counter.”

By a young age he was dabbling in drugs on the streets of New York, and also dabbling in a spot of crime to feed such addictions.

His memoir is in many ways the tale of a young man who refuses a conventional existence. Travelling the European continent, Grogan chronicles Paris, Amsterdam, Rome, London and other great cities which had long attracted American backpackers with a degree of wanderlust.

From Italy, he made for Ireland, writing that he withdrew his last five hundred dollars from the bank, packed one bag full of clothes and another full of books, and then “boarded a plane for Dublin, Ireland, to see if he could get himself straight into the Auld Sod of his forefathers”.

Of the Dublin of 1964, Grogan thought little of Neary’s public house, believing it to be full of “neatly dressed middle class people, talking about the theatre”.

Instead, he felt much more at home in the nearby McDaid’s, remembering how “it was a big, funky room and the only decor was the people in it.” He claims to have encountered IRA activists who took him under their wings, and “invited him to be a man of action as well as letters, and to go North with them”.

The young American claims to have taken part in a frantic border raid, which “blew the wall out of a tiny post on the border of Armagh near a place called Forkill late one Saturday night, and they were back in Dublin when the pubs opened for the Sunday afternoon session”.

Grogan says he lodged at the Brazen Head, the oldest pub in the city, and mingled there among men he described as “short changed by de Valera and his pack of cronies… condemned to bitterness, a meagre pension and a glass of booze or two at places like the Brazen Head”.

After a few months, Grogan left Dublin, on the basis that “he had enough goofs and that he was sick of eating fish and chips all the time and taking wages for a living. Besides, he hadn’t been laid since he’d been in Dublin, because women weren’t allowed in the rooms at the Brazen Head and he didn’t like to pay hookers for the clap.” He eventually found sex in Dublin too, something he took the time to vividly recall.

Yet Ringolevio isn’t just the story of a backpacker travelling Europe; indeed, it could be argued the story of Grogan was only beginning. Back in America, and still in his twenties, he became the driving force behind The Diggers movement in San Francisco, right there during the Summer of Love.

They were all about freedom – keeping things free and staying free. From free food the focus turned to clothes, education and even recreational drugs. Grogan and The Diggers refused cash donations, and he sometimes burnt cash to make the point.

In the words of Vanity Fair, Grogan and his people “created the poverty-is-sexy ideology for young panhandlers”. This all sounds like madness (because it was madness) but in the San Francisco of the 1960s it was perfectly normal. “Freedom Means Everything Free” was Grogan’s rallying cry.

Abbie Hoffman remembered that “Emmett Grogan was the hippie warrior par excellence. He was also a junkie, a maniac, a gifted actor and a rebel hero.” Grogan died in April 1978, his body discovered on a New York subway train. One contemporary said that when “Emmett Grogan died of a heroin overdose, the dreams of the ’60s were starting to fade”.

How much of his Dublin memoir was true? When it comes to Grogan, we’ll never know.