What’s the best way to tell area residents about plans for a new asylum shelter nearby?

The government should tell communities directly about plans for new asylum shelters, some activists and politicians say.

Not everybody is in a position to resume normality, artist Aine O’Hara says, and with “Sick Cards”, she hopes those overlooked have a chance to be seen.

When the first national lockdown was declared in March 2020, artist Aine O’Hara was struck by its paradoxical nature.

She recognised the universality of her experience. “Everyone was going through this,” she says.

But she also saw its flipside. “Because we had to stay so far away from each other, it also felt like this really solitary experience.”

In late February 2022, after the majority of public health measures were lifted, that sense of unity evaporated, while her own feelings of loneliness persisted.

She was in no position to relax yet. Diagnosed with both fibromyalgia and endometriosis, O’Hara was among those classified as highly vulnerable to Covid-19.

Worried that she and others with underlying conditions were becoming invisible to the rest of society, her response was to re-launch a lockdown art project titled Sick Cards.

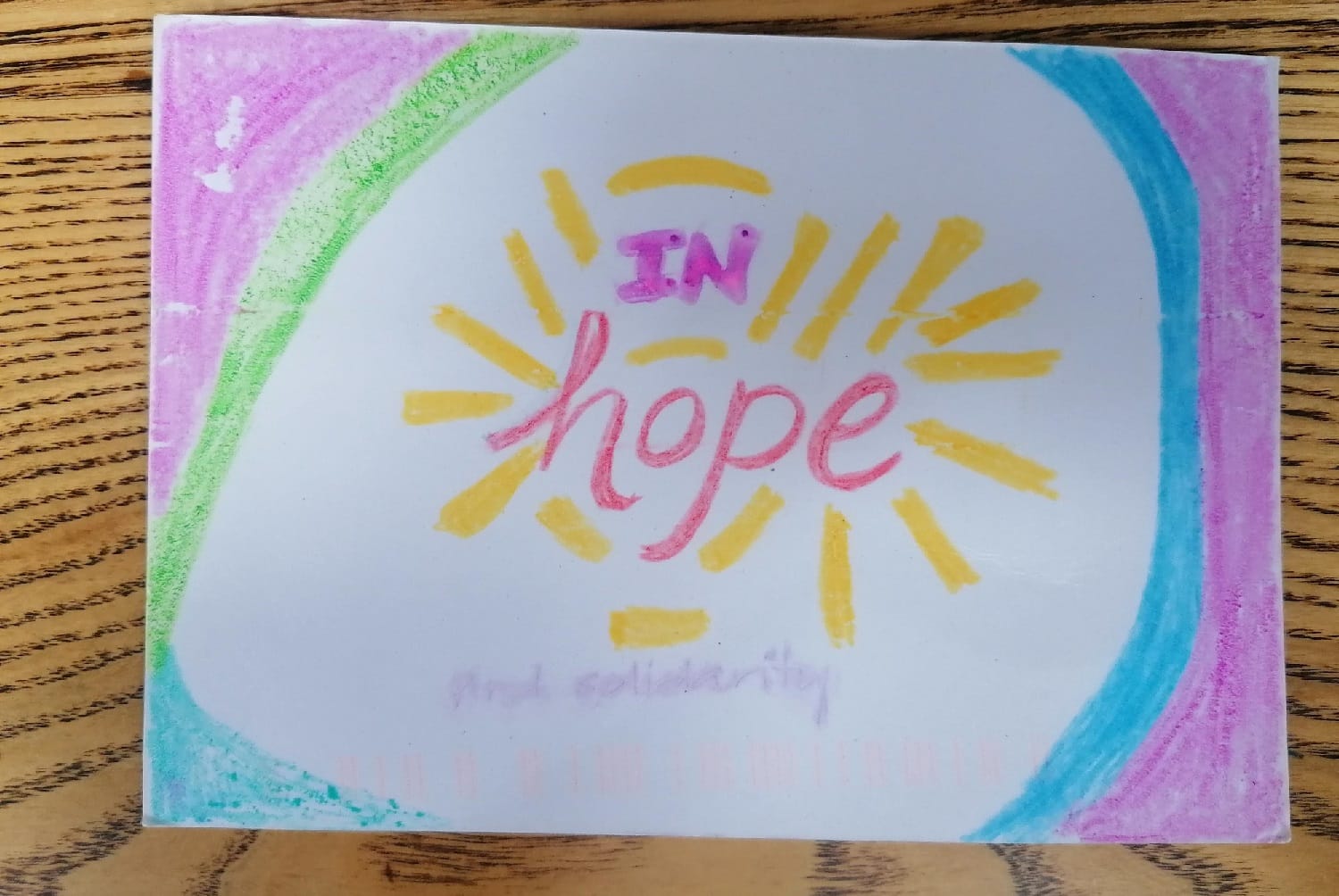

Sick Cards invited people with chronic illnesses and disabilities to connect via the tangible medium of postcards.

Participants were encouraged to express their feelings, whether through creative writing or the visual arts.

“It didn’t necessarily have to do with, like, feeling isolated either,” she says.

For the second round however, which is currently underway, O’Hara’s objective is much more pointed.

In her own postcard, sent out to all potential new contributors, she wrote: “It’s been a terrifying few years and now I feel like we are being totally left behind. (Even more than usual).”

Says O’Hara, “Everybody is in this collective denial where we are all like, ‘No, it’s normal, there’s no more virus, it’s fine’.”

Not everybody is in a position to resume normality, she emphasises, and with Sick Cards, her hope is that those overlooked have a chance to be seen.

O’Hara came up with the Sick Cards project during her residency at the Axis Ballymun centre in 2020.

The residency was specifically for artists with a disability and she had applied before the outbreak of Covid-19.

A multi-disciplinary artist who travels between Dublin and Mayo, O’Hara had initially planned to develop a theatre show around the Irish healthcare system, she says.

“I was already thinking about how disabled people and sick people are treated in this country, and whether or not they have access to adequate care,” she says.

The sense of isolation that stemmed from issues of access, she says, was the throughline between her original vision and the eventual postcards concept.

What changed however, was her focus on community. “When I went into the residency, it became much more about community building and what we can do for each other.”

In April 2021, she launched the first round of Sick Cards, with the open call garnering a large and eclectic response.

“People were writing poetry about living in care homes, writing about their fear in those spaces, especially during the height of the pandemic.”

Contributors submitted postcard collages and simple messages, such as “Keep Well”.

Some fell back on humour, she says. “There were doodles and jokes, or people would write one word like ‘rest’.”

Mairéad Folan, the creative director of the NoRopes Theatre Company in Galway, sent in a poem.

It was told from the perspective of an empty theatre’s ghost. “They [the audience] rarely see me, but they know I’m there,” she wrote.

“My memories alone occupy the space/ And I wait/ The allure will bring them back/ It always does.”

Folan couldn’t run any theatrical productions during the first lockdown, she says.

What inspired her was a collaborator, Little John Nee, who prolifically live-streamed productions via Facebook.

A user left a comment on one of the livestreams about theatre ghosts. “With theatres closed at that time, I wondered what would it be like to be a ghost who cannot see anyone, not even the technicians?” says Folan.

Folan wrote the poem to get it out of her system, she says. It wasn’t intended for anyplace at first, until she came across O’Hara’s project.

With Sick Cards, Folan says she appreciated the fact that the artistic angle was secondary to its fundamental purpose.

“If you wanted to draw a picture of a dog, grand, or just say ‘hi’ to Aine, you could do whatever,” she says. “It was about keeping connections to remind people that you are there.”

The call for Sick Cards II was put out in late March 2022.

O’Hara’s aim, she says, is that the submissions from both of these rounds can be exhibited online and in-person at the Axis Centre this October.

“I’m excited to see what comes of this round and compare the two,” she says. “Has the mood changed? Are we more positive?”

Her own perspective has shifted.

In the postcard she sends to new participants, she writes, “I have been feeling extremely isolated recently and I know I am not the only one”.

Her fear is that, as society tumbles towards some semblance of normality, little consideration is being paid towards those who remain socially distanced.

This time around, her message was more political, as she says, presently “we’re experiencing a mass disabling event.”

“My card talks more about how we need to be aware that a lot of the push to return to normal is economic and governments do not necessarily have our best health interests at heart,” she says.

She herself saw an unprecedented rise in opportunities to work and to engage with the art world, during the pandemic.

Remote work opened up more projects, she says. “Things were suddenly accessible. I was able to watch shows from my bedroom.”

Tara Carroll, an artist, curator and collaborator of O’Hara’s agrees. The art world saw a sudden shift in accessibility, she says.

“That includes people who are chronically ill and disabled, but also people who live in rural areas or have no access to public transport, and can’t go to the city for art events,” she says.

Carroll says hybrid events – simultaneously staged online and offline – are the way forward.

“Aine and I will be doing a lot of events over the summer, and we’re going to do every one of them as hybrids,” Caroll says.

Such aspects of the pandemic are important to hold onto, Carroll says. “Because they included so many more people, and we can’t just go back to the way things were.”

Carroll didn’t have a chance to partake in the first round of Sick Cards. But, she is stewing on a couple of ideas for the second batch.

Her current thought is to create a response to a type of waiting-list letter that has come through her postbox more regularly in the last six months.

Invariably, she explains while laughing, these letters ask if she wants to remain on a waiting list, which she has been signed up to for sometimes two or three years.

“I think I would like to respond to that with a message like, ‘still waiting’, ‘constantly, still waiting for care’ or ‘still waiting for change to happen’,” she says.

“I want to work around some of the wording that comes in all of those letters and draw on that,” she says.

As O’Hara waits on more postcards to be sent into the Axis, she says so far it has already worked. “It’s made me feel more connected.”

“You’ve been experiencing this event, and it’s just you. But here are 100 people having that same experience,” she says. “It made me feel a little more powerful.”