What’s the best way to tell area residents about plans for a new asylum shelter nearby?

The government should tell communities directly about plans for new asylum shelters, some activists and politicians say.

In their latest take on foodie regeneration, the Redrawing Dublin team visit Wuff and note the locked park just a short stroll from the restaurant. They argue that there’s a lack of publicly accessible greenspace in the inner city.

In their Feeding Regeneration series, Redrawing Dublin explore how restaurants can help to regenerate areas, with articles that review restaurants and also the challenges facing their neighbourhoods. There’s more on the idea behind the project here.

We are back in Dublin 7 in the northwest inner city this week for our Feeding Regeneration review. The location: Wuff.

Wuff was a trailblazer and has driven foodie regeneration in Dublin’s inner city since it opened in 2012. Just under four years and a change of ownership later, it’s still going strong. Bookings are essential most weekend evenings. It is closed from Sunday to Wednesday in the evenings.

Walking down Benburb Street from the direction of city you very quickly notice Wuff with its bold red signage above its industrial chic, metal mesh façade.

The restaurant occupies a quaint Victorian red-brick building on a busy corner of Benburb Street. On one side of the restaurant, directly outside the front door, the Red Luas whizzes by every 10 to 15 minutes. On the other, heavy traffic and double-decker buses trundle along Blackhall Place.

Yet as soon you settle in, you discover that this place is surprisingly quiet and a beautiful calm space.

We arrived while they were still offering the early bird menu (€19.50). Early bird menus can generate slight anxiety for some people, but we decided to take the risk.

For the first course, we took the crumbed goat’s cheese and herb salad, which included sundried tomatoes, pesto, mixed leaves, black olives, artichokes and red onions, and the battered king prawns with rice and a lemony herb salad.

With mouth-watering descriptions, we had high

expectations.

The pickled artichoke seemed to have been taken out of a jar. The goat’s cheese was unfortunately reminiscent of an M&S dinner for two. It looked good, tasted good, but gave the sense that it was half cooked elsewhere.

It was not much different with the prawns. Both dishes were tasty, but didn’t excel beyond the ordinary. To be fair, it is what you would expect from an early bird menu.

For the main course we ordered the pan-fried fillet of hake served with wilted baby spinach, pan-fried baby potatoes, sour cream and chives and rougail sauce. We also got the vegetable and nut tagine, which had mixed vegetables with almonds, dates and raisins in a spicy sauce served with bulgur seeds and chilli yogurt.

The hake was done precisely how you should pan-fry hake. It was soft inside but carefully not undercooked, the skin remaining intact with the right crunch sound when you peeled it away. It was delicious.

The surprise in the dish was the inspired, sprinkled spiced tomato that contrasted with the plain potato and spinach sitting under the fish. Is this what they meant by rougail?

The vegetarian Moroccan tagine was a little hesitant and unadventurous, conservatively subtle, as if the chef didn’t want to risk challenging anyone’s palate.

It was on the edge of spicy, with a slight sweetness from the carrots that dominated the dish. The nuts were there, but could have played a bigger role in the dish. Somehow the dish tasted more like a type of ragu rather than a tagine.

Rounding It Off

For dessert, we opted out of the early bird menu and selected the chocolate fondant with pistachio ice cream and almond biscuit. This was a wonderful dish.

The chocolate fudge was creamy and delightfully mucky in colour and texture, all muddy, melted, and milky. The pistachio ice cream was smooth and creamy but had a slight icy taste, which usually comes from refreezing. The pistachio flavour shone through, and the taste didn’t bamboozle with sugar.

The almond biscuit had beautiful crunch but a slightly residual doughy aftertaste. Perhaps from baking powder?

Overall the presentation of the dishes was classic with a high aesthetic awareness. One suggestion though to the chef: perhaps trust people’s palate to take greater risks with the flavours of the tagine.

The service was friendly, attentive and wonderfully unintrusive. In a small restaurant that’s important and not always easy to pull off. The acoustics and ambient music were equally good.

This is an intimate restaurant, with tables quite close together, but you manage to feel cosy and private.

Wuff is a charming restaurant, a significant and wonderful contribution to the street and immediate neighbourhood. It is a beacon of hopeful regeneration in the evenings.

Apparently President Michael D. Higgins pops by occasionally for breakfast.

Benburb Street has long since lost its red-light trade. It is home to one of the state’s most beautiful museums, at Collins Barracks. And directly across the road from Wuff is the wonderful Old Butchers Studio and the Wool Felt Shop, a relatively recent arrival to the street.

If only Dublin City Council could do something about the dreary dereliction and open Croppies Acre park.

Our local regeneration angle for Wuff is the local park at Croppies Acre just 200m further up the road along Benburb Street.

The obvious choice is the dereliction on Benburb Street, which is all too visible and unfortunately all too common, but we discussed the challenges of dereliction to inner-city regeneration last week.

Croppies Acre is the largest park, or local green space in the north-west inner city. It has been closed and locked, for some four of five years now.

Apparently the park was closed because of antisocial behaviour. Why is this considered a reasonable explanation for the closure of the largest green park in the north-west inner city?

Ironically, now that the park is closed to local residents and tourists — who can often be seen, perplexed, rattling the locked gate — it has become an even greater magnet for all sorts of antisocial behaviour.

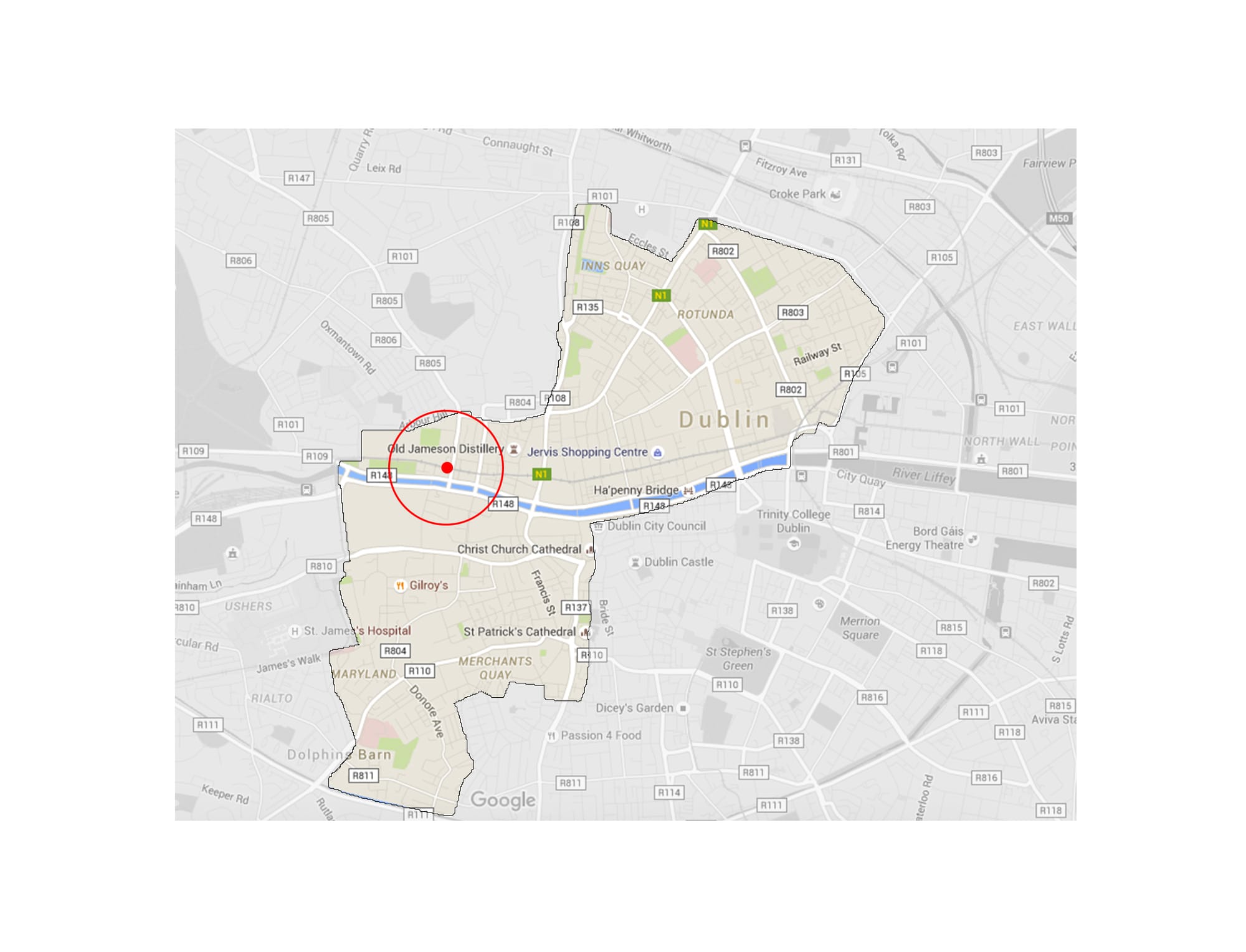

The four- or five-year closure of the park is all the more remarkable given that the inner city, which we have marked out in our map, has an acute deficit of green, publicly accessible open space.

Its largest green space is the grounds of King’s Inns. It is neither a public park nor ordinarily opened to the public at weekends.

Another significant green space, the Incorporated Law Society sports grounds at Blackhall Place, which is just around the corner from Wuff, is practically invisible and not ordinarily accessible to the public at all.

Along with Croppies Acre, these three green spaces make up roughly a third of all the open space in our inner city, Northside and Southside.

Now for some geeky but revealing hard facts. Brace yourself for the data avalanche. It’s actually kind of important.

Just 3.5 percent of the total surface area of the inner city as we define it is zoned green open space by Dublin City Council. This compares to 25 percent of all zoned land for the city as a whole.

A closer look, which considers density too, uncovers an even greater deficit. Some 48,000 people, or one in twelve (9.1 percent) of the city’s population live in our inner city.

This 9.1 percent live on less than 4 percent of the land area of the city, yet these high-density dwellers enjoy a mere 0.56 percent of all designated open space in the city.

Looking at it from another perspective, there is approximately 2,500 hectares of (designated zoned) open space in Dublin city. With a total city population of 527,000, that’s a density of 204 people per hectare of open space. (I’ve rounded here.)

This works out at 49 sqm of municipally designated, mostly green open space for every man, woman and child, the equivalent of a one-bedroom-apartment-sized park for every citizen of the city.

In the inner city, there are just 14.5 hectares of land zoned open space. With a population of 48,000, that works out at 3,296 people per hectare of open space, or just 3 sqm per person, the equivalent of a large dining table of green space per resident.

That’s a staggering 15 times less open space per person in the inner city than for the city as a whole.

This imbalance is all the more remarkable considering the demands on inner-urban areas that do not exist in the suburbs: the daily tide of office workers and the seasonal influx of tourists, and the fact that the local residents are much less likely to have access to a private garden than their suburban cousins.

In addition, people on lower incomes are much more likely to be reliant on public services and public goods. The availability and accessibility of quality public parks is an important public good.

The presence of local parks or accessible public gardens does not tell the whole story. Trees on urban streets are important in how an area is perceived, how it perceives itself, and how it is enjoyed as a desirable place to walk around, live or work.

The pruning and management of trees, and the removal of dead leaves is a direct, but rarely discussed public subsidy of affluent neighbourhoods. Perhaps not surprisingly, the inner city fares poorly in this regard.

Huge swathes of the arc are simply devoid of urban greenery of any kind. Compared to Dublin 2 and 4 or well-established, mature working-class suburbs, the inner city is relatively barren of street trees.

The lack of trees along the Luas Red Line, Summerhill, Seán McDermott Street or Cork Street is as telling as it is noticeable.

Redrawing Dublin recently began a street-tree project with UCD and Workday, a high-tech company in Smithfield in part funded by Dublin City Council.

Our research shows that Ballsbridge-Sandymount has four residents per street tree. Ballybough-Summerhill has 130 residents per street tree.

Using data such as air pollution, population density and walking patterns, Street Tree allows the city to better identify where street trees should be planted. This is part of a bigger bolder project, Mapping Beauty. More about that another time.

The street-tree project aims to help shed light on how city officials make decisions, empower local communities, and help to grow “a greener, more liveable, economically dynamic and socially just inner city”.

We need an ambitious tree-planting and public-space improvement programme in disadvantaged inner-city communities, perhaps funded by ring-fenced local development levies.

Compared to suburban areas with plentiful green space, or the leafy tree-lined streets of Dublin 4 and Dublin 2, does Dublin’s inner city have its fair share of “green expenditure” by Dublin City Council?

It’s happening. It’s great to see a new council park opening on Cork Street. The recently announced plans to reimagine St Audeons Park at Christ Church are also inspiring.

And the new asphalt paving in Croppies Acre would suggest that the council intends to open this Benburb Street park soon. Here’s hoping.

How do we score? We’ve come up with our own super-geeky marking system: 40 percent for food, 30 percent for the experience, 20 percent for the “regeneration impact”, a subjective take on the impact of the restaurant on the immediate area, and 10 percent for value for money.