What’s the best way to tell area residents about plans for a new asylum shelter nearby?

The government should tell communities directly about plans for new asylum shelters, some activists and politicians say.

There is perhaps nobody as significant to the story of collecting Ireland’s oral folk tradition as Séamus Ennis, who was born a hundred years ago this May.

In recent years, Dublin has witnessed something of a renaissance of traditional and folk music, which has even propelled acts like Lankum to international attention.

Central to all of this is the oral tradition, as songs and reels make their way through the generations and find new audiences. There is perhaps nobody as significant to the story of collecting that oral tradition as the great Séamus Ennis, born a hundred years ago this May.

From Fingal in north County Dublin, Ennis was a legendary uilleann piper and collector of songs and tunes, travelling all over Ireland on a trusty bicycle in search of ceol dúchasach (native Irish music), against the backdrop of the hungry 1940s and ’50s. His collections are today deposited in the National Folklore Collection, capturing an Ireland that could well have vanished in his absence.

The life of Séamus Ennis would have been very different were it not for his father, civil servant James Ennis, chancing to enter a pawn shop in London.

Drawn immediately to a set of uilleann pipes on display and for sale, he purchased them without hesitation, discovering later that they had been made on Thomas Street in Dublin. Beginning at the age of 13, Séamus learned the complex instrument from his father.

In time, the younger Ennis developed a keen appreciation for the need to capture Ireland’s rapidly vanishing disappearing oral tradition.

At the age of 23, in 1943, with Europe at war and rationing a feature of Irish life, Séamus Ennis took off on an amazing journey through Ireland. Giving him “pen, paper and pushbike”, the Irish Folklore Commission entrusted this young Gael with the task of recording and documenting the oral and music traditions of rural Ireland.

As Ríonach uí Ógáin notes in the introductory essay accompanying Ennis’s diaries, by the 1940s modernisation and emigration appeared to threaten a rich heritage, heralding “a speedy decline in many aspects of a hitherto relatively unchanged lifestyle and its associated traditions, especially in storytelling in Irish”.

Ennis was paid almost £3 a week, and it was difficult work – the rural communities that he visited were sometimes insular places, and he cut a funny shape, one account remembering him as “long in the leg, famished looking, thin-shouldered and nervous”.

Reading Ennis’s diaries from his years travelling Ireland in search of songs and stories, it is evident that the Dubliner cherished each moment.

Take his account of visiting Carna in Connemara in July 1944, where “a few lads and girls gathered in and we had a great night’s music and dancing in a house. The man of the house – Breathnach – is one of the great old-style dancers. We left the house at 5.30am after a great night’s sport and music and dancing. Went to bed at eight o’clock.”

In time, Ennis went from being the curator and gatherer of oral traditions to the subject of another collector.

In 1951, the famed American folklorist, oral historian and archivist Alan Lomax arrived in Ireland, in the company of folk singer Jean Ritchie. Lomax, keen to capture the musical traditions of all cultures, believed Ireland’s heritage particularly worthy of recording, as “the last notes of the old, high and beautiful Irish civilization are dying away. A civilization which produced an epic, lyrical and musical literature as noble as any in the world.”

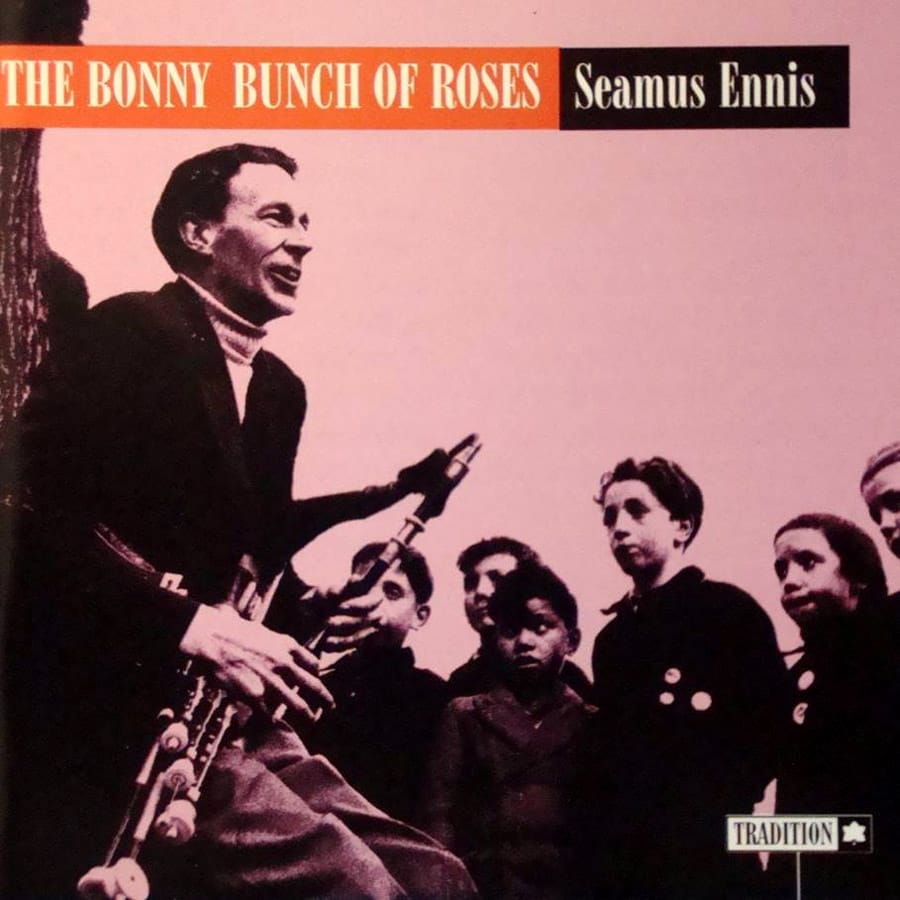

The images of Ennis captured on that trip are beautiful, including him playing his uilleann pipes before an audience of curious children in Dublin’s Phoenix Park.

Ennis had a pivotal influence on a generation of young Irish musicians, including both Liam Óg O’Flynn and Christy Moore of the pioneering group Planxty. Liam Óg, a piper himself who inherited the pipes of Ennis, remembered that it was his love for capturing tradition that set Séamus apart, as “he was this incredible musician, but most incredible musicians like that don’t tend to go into the background of things in any sort of academic or structured way…Ennis combined the two”.

As a recognised expert of his field, Ennis presented As I Roved Out for the BBC, an important moment in the history of folk-music broadcasting, bringing Irish voices into thousands of British homes.

Ennis played before packed halls in the UK’s thriving folk-music scene too, with Bob Davenport remembering the electric effect of his playing of audiences, as “like watching a cowboy film where the marshal walks in and everybody looks round. When he played, there was nobody ever comes close. It stood your hair on end. It was just absolutely devastating.”

As the folk- and traditional-music revival of the day began, Ennis was a respected elder around younger musicians, performing at events like the Newport Folk Festival and Lisdoonvarna.

Ennis died in October 1982, having lived out the later years of his life in the familiar surroundings of north County Dublin, in a caravan he christened Easter Snow. In a song of the same name dedicated to his memory, Christy Moore recalled how “He called up lost verses again”.

And yet, the verses were not lost. It was Ennis who captured them, ensuring their place in the archives and the continuation of ancient tradition.

A statue at the Naul honours his memory, and the Séamus Ennis Cultural Centre continues to host live music. His abiding legacy, however, is his recordings, which retain their power.

In the words of traditional musician Tony MacMahon, “He made me realise music is magic and a spiritual experience. It cannot be taught in any university. It is beyond that.”