What’s the best way to tell area residents about plans for a new asylum shelter nearby?

The government should tell communities directly about plans for new asylum shelters, some activists and politicians say.

Researchers studying fabrics in Ethiopian books from the 1400s to the 1900s found they had come from as far west as England and as far east as China.

The upstairs gallery at the Chester Beatty Library is dark and cool and calm on Friday, speakers quietly playing what sound like religious chants.

This Sacred Traditions exhibition is showing off “sacred texts, illuminated manuscripts and miniature paintings from the world’s great religions and systems of belief”.

In a row of display cases – deep-purple, glass-fronted nooks – sit a series of Christian treasures from Ethiopia, two scrolls and three books. The books, from the 18th and 19th centuries, feature not only covers, spines, and pages – but also fabrics.

One is labelled “The Homilies of SS Michael, Gabriel and Raphael, and the Miracles of St Raphael”. A big, heavy-looking volume, it is open to the middle, and a gauzy “curtain” hangs between the pages to keep its colourful illustrations and carefully formed writing separate and safe.

Two others – a prayer book and a psalter – are closed, their exteriors wrapped in cloth. These fabrics are beautiful in themselves, still colourful after all these years: one with a red and white pattern, the other with stripes of marigold, purple and green.

But, also, studying fabrics in Ethiopian religious books can help to reveal the trade routes, and the ways in which Ethiopia has been linked for centuries into global trading networks that reached from England to China.

That’s according to a panel of experts who spoke at a talk last Wednesday put on by the Chester Beatty, titled “Ethiopian Manuscripts and the Early International Circulation of Textiles”.

“At the end of the day, what this is giving us is a kind of a bird’s-eye view of the trade in textiles for the last 600 years,” said Michael Gervers, on a video call after the talk.

During the talk, the researchers focused on swatches of fabric pasted into the inside covers of Ethiopian religious books, between the 1400s and 1900s.

None of these swatches are on display at the Chester Beatty right now, but there are some among its collection, which can be viewed online.

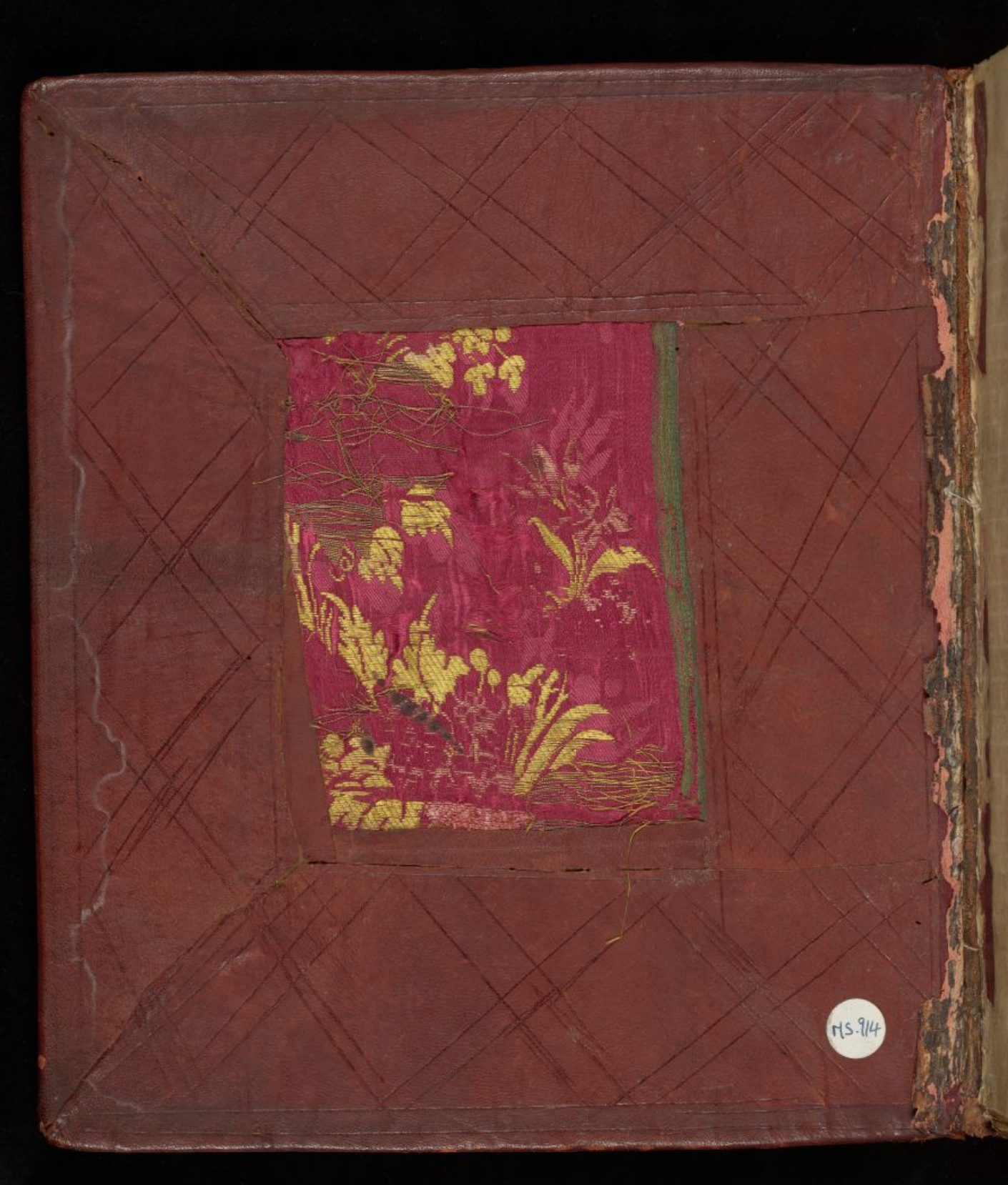

The Chester Beatty has seven manuscripts with fabric swatches inside their front covers, said Rosemary Crill, a specialist in South Asian textiles. Like this 18th-century manuscript, with a swatch of red and yellow fabric inside its front cover (above).

Among the speakers was Michael Gervers, a professor of history at the University of Toronto, and the principal investigator of the Textiles in Ethiopian Manuscripts project.

As a graduate student in the 1960s at the University of Poitiers, he helped excavate a rock-hewn church in France, he said during a Zoom interview Friday.

On the dig, he met a professional archaeologist from Hungary, who he later married, Veronika Gervers-Molnár. She moved to Toronto and got a job at Royal Ontario Museum in the textile department.

She died in 1979, but Gervers maintained an interest in both textiles and rock-hewn churches, which naturally took him to Ethiopia. “Ethiopia has the most incredible rock churches of any country in the world,” he said.

He visited in 1982, meaning to visit some of them, but with the Derg – a Marxist-Leninist military dictatorship – in power, he wasn’t able to, Gervers said. Instead, he spent his time there studying Ethiopian textile manufacturing, he said.

In 1993, he went back to Ethiopia with a small team and digitised and photographed manuscripts and ecclesiastical antiquities, he said. These are now available to researchers in an online database.

“So both interests have been going on together,” Gervers said.

While he’d been studying both textiles and manuscripts, though, Gervers hadn’t been studying textiles in manuscripts.

That changes through contacts with colleagues studying books and the Silk Roads, he says.

And at a 2021 workshop, Gervers and Eyob Derillo of the British Library gave a talk on textiles in Ethiopian manuscripts – alongside talks on Syriac, Armenian, Kashmiri, Chinese and other manuscripts.

When Gervers’ research assistant, Carolina Almenara-Melis, searched the web and the database of Ethiopian manuscripts Gervers and others had digitised, she quickly found almost 1,000 examples of textile swatches in front covers.

“It was very clear from the results of her work that we were looking at something important,” Gervers said.

They realised that the examples she found went back as far as book bindings, leather-wrapped wooden boards sandwiching manuscript pages, Gervers said. “The earliest we found so far is the late 15th century.”

And “they’re still doing it – less, much less particularly since the Second World War, when more modernisation reached the country – but the scribal tradition has continued”, he said.

So where did these fabric scraps come from, and why did people take the trouble to paste them inside the covers of books?

“These textiles are coming from as far east as China and as far north as England,” Gervers said Friday. “I’m not sure that we’ve identified anything that has been particularly Irish, but it’s not without possibility.”

It shouldn’t be a surprise that Ethiopians were getting fabrics from all over the world, said Sarah Fee, a senior curator of global fashion and textiles at the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto.

Even 2,000 years ago the kingdom of Aksum, based in what is now northern Ethiopia and Eritrea, was tied into major trade routes reaching Europe, South Asia, and other parts of Africa, Fee said.

In the period the talk last Wednesday focused on, there was a dense network of trade routes connecting the entire world, including Ethiopia, Fee said.

During the talk last Wednesday, Philip Sykas, a visiting research fellow at Manchester Metropolitan University, spoke about how English printed cottons got from Lancashire to highland Ethiopia.

For the most part, they were sent to Bombay first, Sykas said. After the Napoleonic Wars ended and it was safer for merchants to sail the seas, English merchants sold to India cheaper printed versions of India’s own famous cotton textiles, Sykas said.

From Bombay – now Mumbai – local merchants with long-established connections to Arabia and East Africa would have brought these Lancashire fabrics to ports within reach of Ethiopia, Sykas said.

Traders brought textiles by ship to ports on the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden: along the coast not too far from Ethiopia, basically, Fee said.

From there, camels and mules carried goods up into the highlands, through a system of warehouses, fairs and markets, Fee said. Caravans might include up to 700 men and 3,000 camels, she said.

Not only did merchants bring fabrics to Ethiopia to sell, but Ethiopian elites sent agents abroad to bring back fabrics they wanted, Fee said.

They sent agents to Egypt, India, Greece, and Persia, Fee said. They traded things like ivory, gold and horses in payment, she said.

Beyond commercial trade, ambassadors might have brought fabrics to Ethiopia as gifts from foreign rulers, Fee said. Ethiopian rulers both received and sent ambassadors.

Between 1400 and the late 1520s, the Ethiopian court sent ambassadors to places like Rome, Valencia, Naples and Lisbon, she said.

In Ethiopia, these imported fabrics were mostly for elites, said Gervers.

“The wearing of cotton cloth was probably reserved to the upper classes for quite a long time,” he said Friday. “Meanwhile, the rest of the population would be wearing leather.”

So how did these fabrics get from China or Manchester to East African ports to books in Ethiopian churches?

One possibility is that they first went to court, where they were made into clothing and then used, Gervers said Friday. “And then somebody took a snip out from the clothing when it was worn out, or when the person died, and put it into the manuscript,” he said.

There are several examples of swatches with seams in them that are pasted into books, indicating that they had been used for something else first, Gervers said.

Another possibility is that the fabrics might be related to holy figures, he said. “We wonder if they’re not relics,” he said.

Whatever the case, it is relatively rare that fabric swatches were pasted into books at all in Ethiopia, Gervers said. “It only occurs 15 percent of the time, so 85 percent of the time, people didn’t bother to put them or there was no cause to put them there,” he said.

The researchers aren’t sure yet on what basis the makers decided to put swatches into some books and not others, Gervers said. But they’re working on it.