What’s the best way to tell area residents about plans for a new asylum shelter nearby?

The government should tell communities directly about plans for new asylum shelters, some activists and politicians say.

One of curator Paul Maher’s jobs has been to track the timing of the bud-bursts and autumn colours each year, feeding his data into a European network.

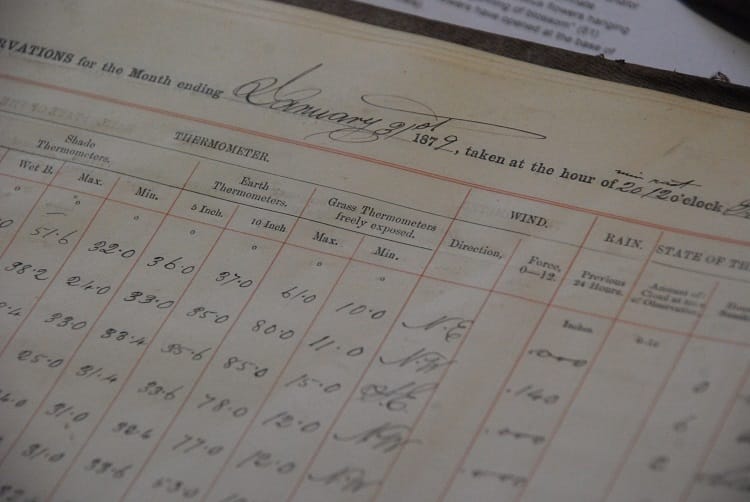

“We record everything here,” says Paul Maher, pointing to volumes and tomes dating back to 1875.

In his stately office at the National Botanic Gardens in Glasnevin, where he been curator for 14 years, he digs out his phenology sheets, the meticulous records of how the patterns and behaviours of plant species have varied over his tenure.

Maher has several duties at the gardens. As curator, he promotes them, designs the bedding and landscaping, and manages staff.

But he is also charged with conducting the garden’s phenological readings every spring and every winter, a task he carries out alone.

The data collected and observed over time can help track climate change at a local level, but it is far from straightforward, says Maher.

The Botanic Gardens is a city garden, so pollution and other factors such as street lighting and traffic can make it difficult to spot meaningful patterns.

Maher gathers his data in different seasons.

He tracks autumn colouring and leaf-fall for the most part in November. The bud-burst readings happen in April.

Each spring Maher takes his list of 11 species – from alpine currant, to Norway spruce, eared willow and grey poplar – that are dotted around the gardens and records if and when their buds are flowering.

“Phenology is ancient. It’s goes back, probably, about 3,000 years,” says Maher. “But cities are notoriously difficult to gauge what’s happening with your climate.”

Maher explains how the front and back garden of a Dublin house could have distinctly different climates. “You could grow a different range of plants in the front as you can in the back,” he says. “It’s down to traffic, it’s down to street lighting, pollution.”

“If you look at Robinia (black locust), for example, you can only grow it in a front garden in Dublin that’s on the street,” says Maher. “Can we grow it here at Glasnevin? No, we can’t. It’s extremely curious. Cities are fascinating.”

Ireland’s first four phenological gardens – in Valentia in Co. Kerry, the John F. Kennedy Arboretum and Johnstown Castle in Co. Wexford, and the National Botanic Gardens in Dublin – were set up in the 1960s by former director of the Irish Meteorological Service Austin Burke, in partnership with the Botanic Gardens.

The data gathered at these four sites was only properly considered and processed from 2001 onwards, accordingto the Environmental Protection Agency.

Now each year, the data collected is sent to Berlin, where the International Phenological Gardens is based. It’s there that averages are examined and conclusions about climate change are drawn, says Maher.

But at the Botanic Gardens the patterns aren’t what people often expect.

“People who come to talk to me, usually students, are expecting to find me saying to them, ‘Every year there is an extra day or two earlier for our leaves sprouting,’” says Maher. “That doesn’t happen and that’s not the case.”

Instead, the data records singular instances – a late bud leaf or early autumn colouring – rather than cyclical events, in Maher’s experience. In other words, there aren’t many patterns.

Other data gathered in tandem proves a stronger indicator of climate change. “What I’d say is I can show you proof of climate change,” he says. “I can show you our flooding events. I can show you our storm events.”

He could also show you the garden’s horse-chestnut trees, their leaves now blotched with fungus. “A lot of the reason these pests and diseases are now landing on our doorstep is that the cold winters aren’t there to kill them off,” says Maher. “It’s not killing the tree but it’s killing off the leaves.”

Maher points up to the shelves lining his office.

From across the room he lugs over a great, leather-bound ledger dating from 1879. The yellowed pages are lined with carefully hand-written figures recording the temperatures, wind speeds and tidal movements in and around Dublin.

Underneath the Victorian record is Maher’s own handwritten data, dating back to 2003.

He picks up a small, mauve copybook from 1968 with “The Department of Transport and Power” inscribed on the front.

Take Ribes alpinum (alpine currant), for instance. In 1968, its buds burst on 16 April. In 2016 its buds burst on 7 April. That’s expected, says Maher.

But then take Salix aurita (eared willow). It burst its buds on 17 April in 1964, but in 2016 burst its buds on 12 May.

“When you’re collecting and examining data like that you’re always working with averages, but these throw your averages hugely.” Cities are tricky.

Ireland’s National Phenology Network recommended in 2013 that the phenological network should be expanded “across the country”, and that the general public should get involved more.

But for the National Botanic Gardens, there are bigger issues, says Maher. “We’re desperately short of funding. But we’re very conscious that in Ireland today you really can’t be shouting for funding when you’ve people lying on hospital trolleys.”

The Aquatic House, built in 1854, has sat derelict for nearly a decade. And only one scientific expert, Colin Kelleher, is currently employed to undertake research. “We would have had four botanists, six botanical assistants and so we’re down to one,” says Maher.

“As a scientific institution you think, ‘Well, we’re not functioning are we?’ and the answer is no. We’re not functioning scientifically. It’s something we’re waiting with bated to breath to be improved.”

[Correction: Due to an editing error, Maher’s tenure at the Botanic Gardens was misrepresented. It was corrected in the second paragraph on 7 April 2017.]