What’s the best way to tell area residents about plans for a new asylum shelter nearby?

The government should tell communities directly about plans for new asylum shelters, some activists and politicians say.

Included are books, pamphlets and posters of all kinds – some funny, some serious. Each is the only known surviving copy of that particular text left in the world.

On a recent Monday afternoon in Marsh’s Library, Jason McElligott lifts a heavy, leather-bound, embossed tome off a shelf and heaves it open.

“A lot of the time, people will associate a library like this, with something like this,” says McElligott, the library’s director, book in hand. “It’s a Latin, church text, but really, what is there to say about it?”

As McElligott shows off the book, a quiet stream of visitors filters through the Sole Survivors exhibition at this three-century old library in the Liberties.

When staff are putting together an exhibition at Marsh’s Library, there’s always a worry that it’s going to be “a load of little brown books”, says McElligott.

“So it’s little brown book after little brown book, and oh God, another little brown book,” he says, laughing.

With Sole Survivors, McElligott says the staff were conscious of putting together something that would appeal to more than just academics.

The exhibition spans from the 16th century to the 18th century, and includes books, pamphlets and posters of all kinds – some funny, some serious, and some concealed within the pages of larger and more mundane volumes.

The one thing they all have in common is that each one is the only known surviving copy of that particular text left in the world.

When staff began looking through the library’s collection, they discovered almost 400 items that don’t exist anywhere else in the world, says McElligott.

Sole Survivors is made up of smaller books “very ephemeral and read to death,” says McElligott, while most rare book collections are dominated by larger, more decorative, barely touched tomes.

Many of the smaller items survive because somebody hid them within another book, he says. “Sometimes, the most interesting thing in a book isn’t the text.”

Centuries-old schoolbooks turn up a lot, some of them from St Patrick’s Grammar School across the road. Music books were hard to print and are rare, and posters, pamphlets, and flyers are generally lost to the ages.

Among the Cromwellian tax orders, posters detailing Holland’s secret weapon in their 16th-century war with England, and a 65-verse poem to a Dutch bride on her wedding day, there are some gems: snapshots of life in Dublin at the time.

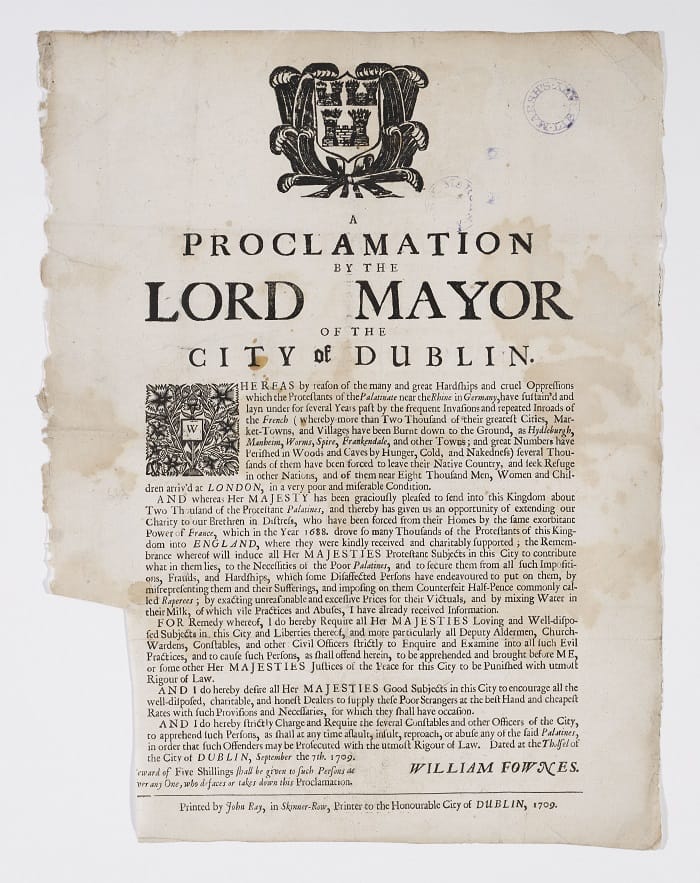

McElligott indicates a poster, dated 1709: “A Proclamation by the Lord Mayor of the City of Dublin”. It urges people to treat “Palatine” refugees well, he says.

William Fownes, an 18th-century Lord Mayor of Dublin, lists the hardships of the Protestants of the Rhineland, where “great numbers have perished in woods and caves by hunger, cold and nakedness”, and “several thousand have been forced to leave their native country and seek refuge in other nations”.

The proclamation warns against “imposing on them counterfeit half-pence”, against mixing water in their milk, and against other vile practices.

This was one of the items that really engaged the staff, says McElligott. “We just wanted to show that in the past, many of the big questions about how to live with each other have been dealt with, and maybe if we take a little time we can learn from how people did it in the past.”

McElligott’s own favourite is a broadsheet from 1743, “for the amusement and entertainment of Ladies, as Well as Gentlemen”, where the advertiser promises “a course of curious experiments”, and “things beyond nature”, including a miniature volcano, and milk that turns to the colour of blood with some special chemistry.

“The guy was a bit of a charlatan, and a showman,” says McElligott, but what’s interesting is that the ladies are listed first.

It’s a turning point, he says, when you start to see women appear more in notices like this, more prominently in the “Ladies’ Answer to the Gentlemen’s Apology” of 1746, following riots at the Smock Alley theatre, when a patron was thrown out for assaulting an actress, and later brought his friends back to trash the place.

“It’s one of the first times in Dublin you get something specifically in a woman’s voice, especially commenting on something men had done,” says McElligott, which he says they call the first #metoo movement in Irish theatre.

“It was important to us to show life going on at the time. Real people living in Dublin. The city could be quite lawless in the 18th century,” says McElligott.

He hopes that visitors will be intrigued that these items exist in one of the most unlikely places you could imagine.

“The library is made up of four scholars’ collections,” he says, and they’re all old, dead white men who were also clerics. But, he says, the exhibition is about looking at them in a different way: as book lovers.

“You come in and it looks like a museum of books, but it was a living collection once, and still is a reading library,” says McElligott. What it says about Dublin is that it was part of a European culture and exchange of knowledge, he says.

McElligot’s main wish for the exhibition, is for people to come away with a favourite item that speaks to them in some way, “a human story from the past that really strikes them. People were more complicated in the past than we give them credit for.”

Sole Survivors runs until the end of the year.