What’s the best way to tell area residents about plans for a new asylum shelter nearby?

The government should tell communities directly about plans for new asylum shelters, some activists and politicians say.

Architect Marion Mahony Griffin “thought very deeply about things” – from the human relationship with nature, to community planning.

The new gallery in the Irish Architecture Foundation building on Bachelors Walk has been transformed into a mind map of the unconventional and accomplished female architect Marion Mahony Griffin.

Influenced by spirituality, nature, and a democratic approach to community planning, Mahony Griffin left behind a large volume of work from the early 20th century.

“She was somebody not to be messed with,” says Sarah Sheridan, an architect and curator-in-residence at the foundation. “She thought very deeply about things, and she was willing to stand up for herself and put herself out there.”

Born to an Irish father and American mother in Chicago in 1871, Mahony Griffin would become an influential delineator – a technical artist – working alongside her architect and city-planner husband Walter Burley Griffin in the United States, Australia, and India.

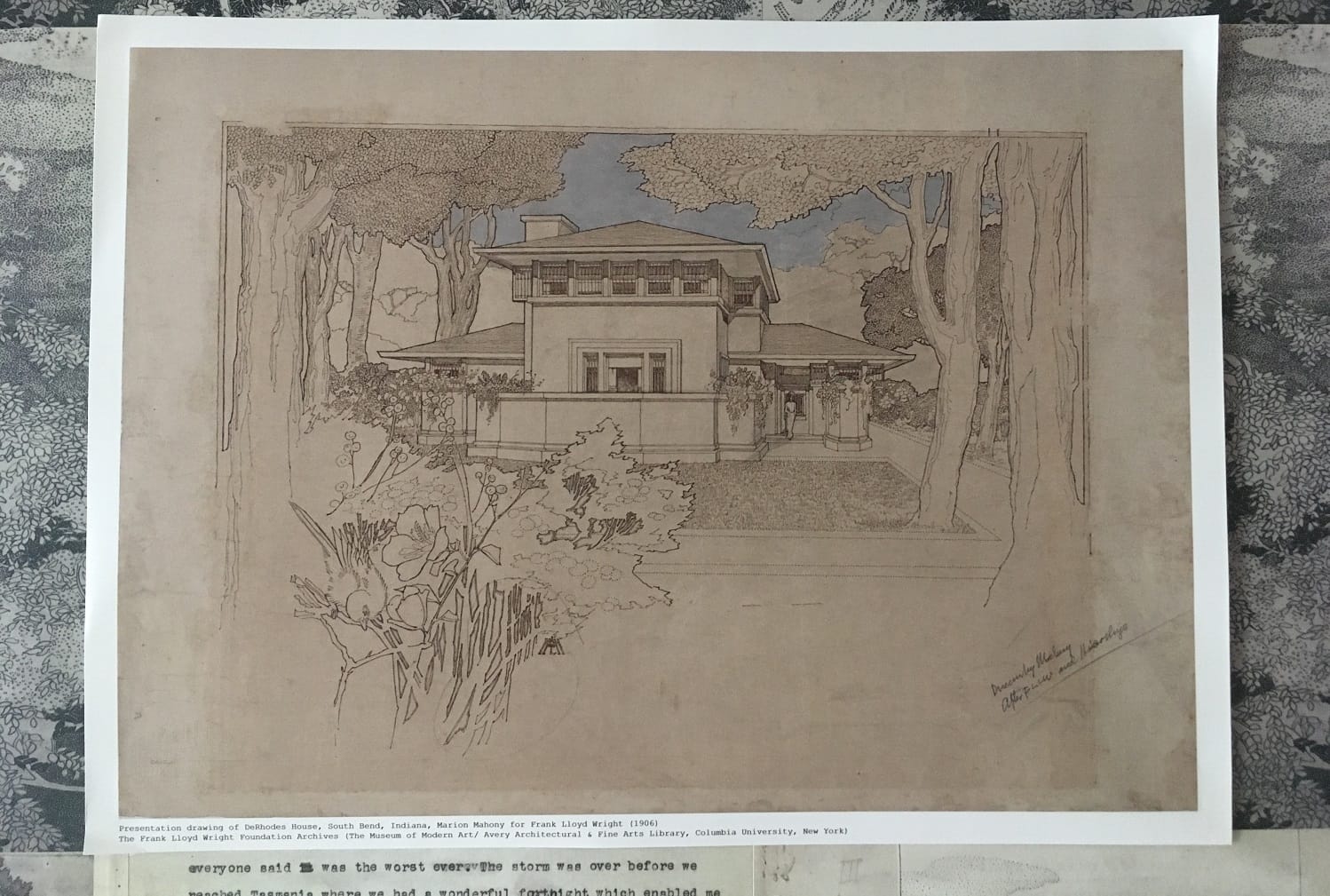

Although she worked for legendary architect Frank Lloyd Wright and drew designs that would shape the Australian capital, Canberra, she isn’t as widely recognised as her male peers.

“We were trying to see why she was pushed aside,” says Sheridan.

Mahony Griffin worked for Lloyd Wright’s studio in Chicago and was one of the founding members of the Prairie School style of architecture, which emerged in the late 19th century.

This style is characterised by horizontal lines, minimal ornamentation, and open floor plans.

This was a departure from “stuffy”, Victorian-style homes, says Brian Ward, an architecture lecturer at TU Dublin, who worked with Sheridan on the exhibition.

“They started to think of a home that was open to nature and its surroundings,” he says.

Among the exhibits at the gallery on Bachelors Walk is one of her tree-planting plans, an intricate and stunning drawing with meticulous indexing of more than a hundred different species of trees.

For Mahony Griffin, it was important that people had a reciprocal relationship with nature, instead of just taking from it, says Sheridan.

Sheridan points to one of Mahony Griffin’s drawings of Mason City, Iowa from 1912. It shows a wide river flowing past scattered houses.

“The roads weave around with the topography,” she says. “The most important thing is the view of the river and to the other side of the ravine.”

The Griffins both believed in a democratic approach to architecture and community planning.

Her buildings would have flat roofs because she wouldn’t want one person to take away the view from a neighbour in the house behind, says Sheridan.

After the couple moved to Australia in 1914, the Griffins designed the recently reopened Capitol Theatre in Melbourne.

Inspired by German expressionism, Mahony Griffin was responsible for the geometric ceiling, which features prismatic plasterwork, lit by coloured lights.

To become experts in Mahony Griffin, Ward and Sheridan – who had a curatorial residency at the IAF – had to think like her.

Mahony Griffin often mentioned idea-sharing in her writing, says Ward. “That’s how she gathered knowledge, and we wanted to replicate that. She was always trying to gather knowledge outside of the realm of architecture.”

They invited artists, botanists, florists, and historians to meet in the gallery space from March to May to discuss Mahony Griffin under different themes, like feminism, nature, and drawing.

“We wanted to make the gallery look like a home studio,” Sheridan says. They took one of her drawings of a gum tree and abstracted it, making it into a wallpaper that runs along the gallery walls.

The exhibition looks at each stage of her life, drawing on Mahony Griffin’s extensive biography of her husband, The Magic of America.

The book is more than 1,400 pages long. Excerpts are mounted along the gallery walls. “We wanted to start with that layer so that everything would be founded on her words,” says Ward.

There are prints of her intricate designs and drawings of Prairie School homes surrounded by trees. There are photos of her husband and of herself, always shot in profile.

The prints are stacked upon the different layers, so it feels like you’re looking at a scrapbook. It’s like how The Magic of America looks, says Sheridan.

Mahony Griffin was the second woman to graduate from Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and the first woman in the state of Illinois to be licensed as an architect.

She was employed by legendary architect and interior designer Frank Lloyd Wright in 1895 to do watercolour renderings.

Her first drawings of Prairie School-style homes were seminal in the school, Ward says, and other architects followed suit.

In an architect’s office, everything is done collaboratively, says Sheridan. He points to one of her drawings of a home. Someone might trace over, then another person might come along and trace over that.

Half of the drawings from Lloyd Wright’s famous Wasmuth Portfolio – a two-volume collection of lithographs – came from Mahony Griffin. “The recognition wasn’t always there,” says Sheridan.

Lloyd Wright would sign his name on her drawings, as he did with other architects in his studio. But, Sheridan says, Lloyd Wright supported women, giving Mahony an opportunity she might not have had elsewhere.

Mahony Griffin worked from Lloyd Wright’s home-based studio, she says. “She might not have been accepted in the corporate offices in Chicago, which were very male-dominated.”

When the government of Australia opened a competition for the design and planning of a new city, between Sydney and Melbourne, the Griffins entered.

The couple drafted plans for the national capital, Canberra, in 1911 and sent them by post to Australia.

Walter was a town planning expert, and Marion used her artistic skills to create the competition-winning technical drawings.

In 1914, the Griffins moved to Australia. There, the couple faced some hostility as outsiders.

For this reason, Sheridan says they believe Mahony Griffin withdrew from engaging with the government, and her husband took the helm on building sites.

“They also didn’t want a woman telling them what to do. It was enough to say that she was an American,” she says.

Some of Mahony Griffin’s beliefs may have caused her to not be taken seriously, says Sheridan.

She said she saw fairies and believed in the spiritual realm. Like several artists in the late 19th and early 20th century, Mahony Griffin was influenced by spiritual thinking.

She was a follower of anthroposophy, a philosophical movement founded by Rudolf Steiner that attempted to make the spiritual world comprehensible from an intellectual perspective.

“Rather than trying to dismiss it, we thought there must be something more to it,” says Sheridan. “It was too easy to write her off as being mad.”

Sheridan and Ward got in touch with the Anthroposophical Society in Ireland to understand the spiritual and “vegetable” realm that Mahony Griffin references.

She wasn’t alone in these interests. W.B. Yeats had a great interest in mythology, publishing the Fairy and Folk Tales of the Irish Peasantry in 1888 and Fairy and Folk Tales of Ireland in 1892.

Sheridan and Ward don’t think Mahony Griffin would have minded that she didn’t become a superstar in her lifetime.

“She was not a victim,” says Sheridan. “It’s not her fault she wasn’t written into history. It was down to things that were out of her control. It makes her even more potent.”

“Marion Mahony Griffin: Discuss” is on until the end of July at the Irish Architecture Foundation’s gallery on Bachelors Walk.