What’s the best way to tell area residents about plans for a new asylum shelter nearby?

The government should tell communities directly about plans for new asylum shelters, some activists and politicians say.

All over the city, there are unexplained features like this one, and Carmen Quigley loves to try to fill in the gaps around what they are, she says.

Carmen Quigley was wandering along Upper Abbey Street one night last year when a glowing beacon above the glassy cylindrical entrance to the Jervis Shopping Centre caught her eye.

“It was lit up in all of its glory,” the illustrator says, while crossing the road at Westmoreland Street on Monday evening.

It was a small round tower with glassy windows at the corner of an inaccessible balcony that wraps around the shopping centre’s car park.

She decided it was a lighthouse, and what ensued was an exchange of emails between herself and one of the centre’s managers, she says while veering into Temple Bar. “The reply I got back was, ‘It’s an empty space. There’s nothing there.’”

“But the mystery is better than the answer,” she says, laughing.

She likes to dwell on sights like these. “You walk past them, and they just become a part of your direction, but you don’t know what they are,” says Quigley.

As she walks by Eustace Street, she points to St Winifred’s Well. “I remember for the longest time not knowing that this was a holy well right here, and there’s even a plaque that says it,” she says.

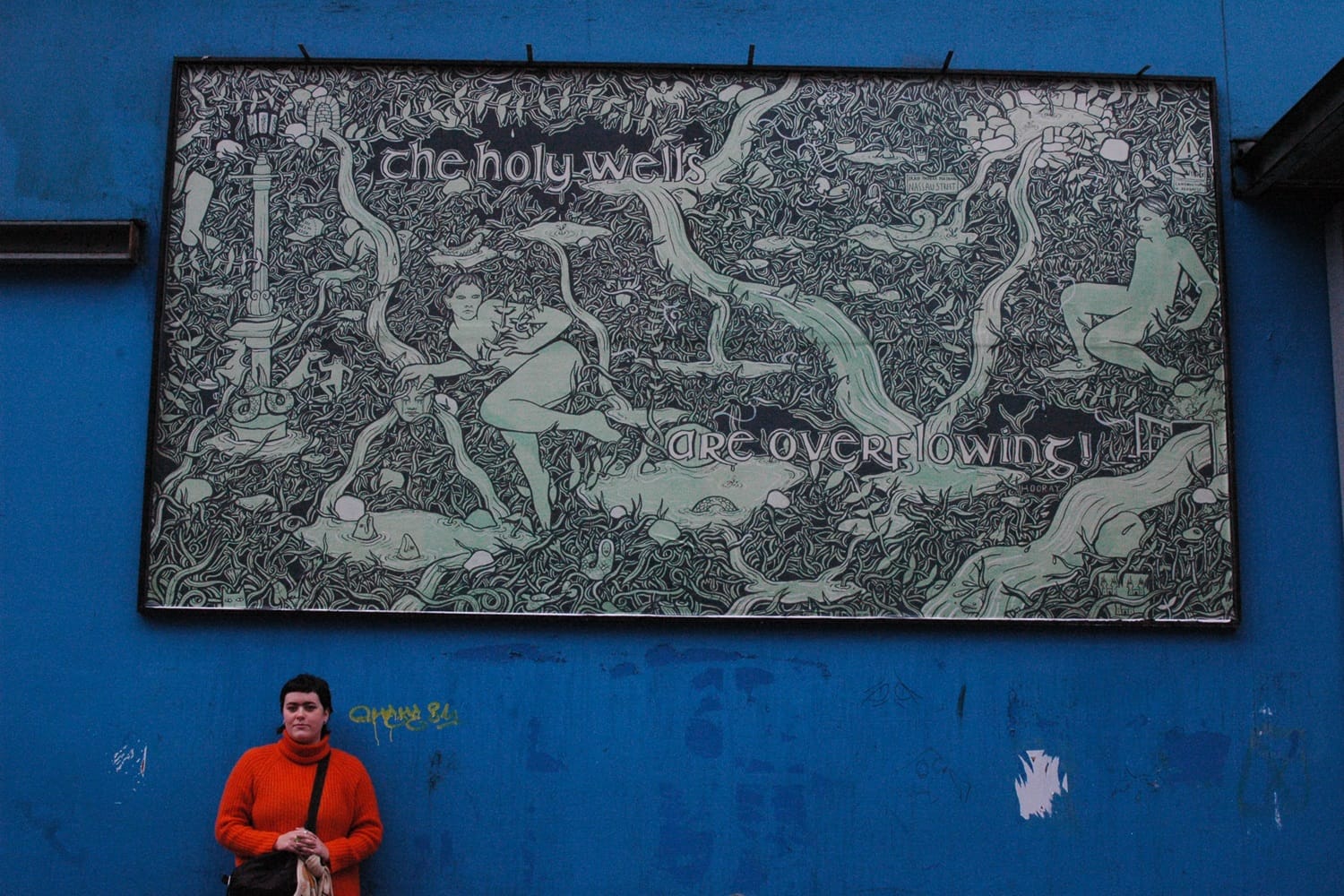

Once she rounds the cobbled bend, Quigley stops outside Project Arts Centre. Plastered across the billboard outside the blue building is her latest work, titled “The Holy Wells Are Overflowing”.

It is a pale green landscape, with vines and streams of water that cascade from a well in the top right corner. Fish poke their heads above the surface, and a pair of nude androgynous figures lie within the tangle.

It could be read as a scene from mythology. But closer inspection reveals an imagined Dublin many years from now.

Hidden within the sprawling vegetation are features of Dublin today: a street sign from Nassau Street, a lamppost from Phoenix Park, the Three Castles Burning city seal. “It’s Dublin,” she says, “but you’re not really going to see Dublin. There are just little nods.”

Quigley calls it a prediction of Dublin’s future and a critique of commodification, in which its holy wells spill out, she says. “And they reclaim the city.”

Quigley’s illustrations draw from Irish and Greek mythology and ancient history. But the stories they tell tend to be plucked from her own imagination rather than any canon.

From Rathmines, Quigley studied fine arts, archaeology and classics.

She found it exciting, she says. “But also I was so bad at knowing the actual facts, because I was more interested in the stories.”

“Like in classics, I would write an essay about the Battle of Gaugamela, Alexander the Great’s fight,” she says. “But I’d just recite it as if it was a story. He had a dream. But I wouldn’t say how many men were in the battle.”

Her works as an artist pursue a similar line. They tell stories that could have appeared in the world of Irish folklore and mythology, she says. “But, it’s as if we couldn’t find any records until now, until I drew them.”

It is grounded in folklore, says painter Juliette Quédec. “But regardless of whether you know the concept behind a piece, everybody who looks at it can come away with their own thing – which mirrors the whole folklore element because folklore is passed from person to person.”

It has evolved into something idiosyncratic, says artist and photographer Garvan Corr. “We shared a studio in our final year at NCAD, and I’ve seen her develop her own language. It’s intricate, and tricky, and it has a real depth.”

Above the desk in her studio off Pearse Street is a small four-panel comic strip in which a long-haired heroic figure emerges from the water, approaching a sword that is trapped in a rock.

But rather than pull it out, they hammer it in deeper, offering a sneaky grin to the reader.

On a canvas hanging from the wall, a moustachioed man pulls the intestines from an alien-like figure with long pointy ears, as it calmly lies among rocks and tangled grass by a pond.

She wants to toe the line between creepy and funny, she says. “I would like to consider it silly, because these are gas. But I don’t know if everyone else finds it to be like that.”

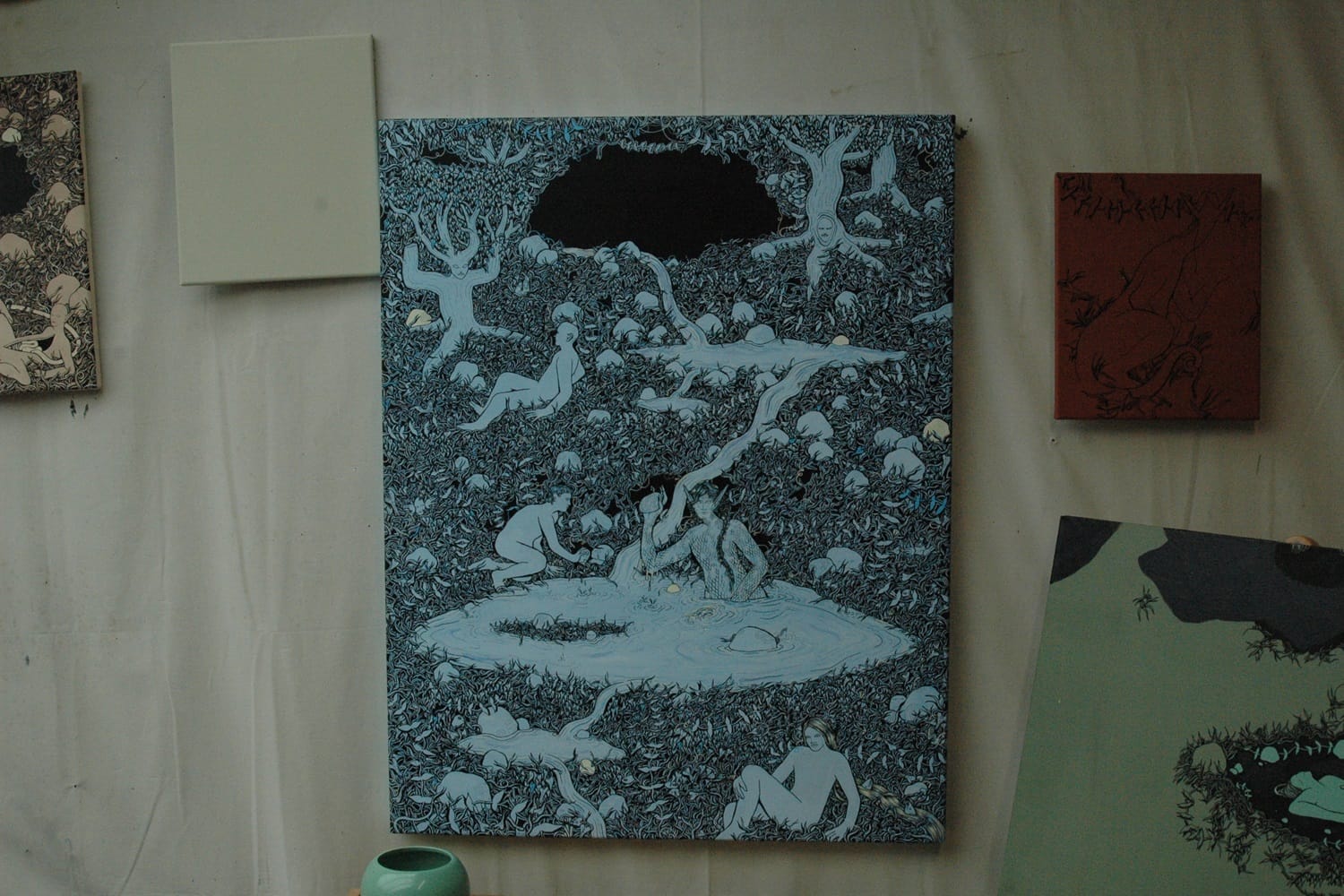

Small critters creep beneath the greenery. Faces appear on trees and rocks, resembling Celtic stone carvings. Abstract patterns akin to pagan triskeles crop up subtly around her main subjects. “They come together like this fever dream,” says Quédec.

In her pottery work, Quigley bridges the gap between folklore and ancient history, says Quédec. “She goes and uses a lot of Ancient Greek motifs.”

That was something she began experimenting with for her graduation show, says Corr. “She started to do vases, and installations around then, testing things out in 3D forms.”

Quigley says she doesn’t make pottery herself. They are found objects, she says. “I pick those pieces up in charity shops.”

Scaly female figures are painted onto small plates. A devil-like sculpture wraps its arm around a miniature vase engulfed in flames.Her choices of subjects include everything from side profiles of Greek emperors, shape-shifting mythic creatures like the selkies and púca, to the cast of The Real Housewives of Beverly Hills.

Quigley steps across the Luas tracks in front of the Jervis Shopping Centre to inspect the “lighthouse” from the busy footpath.

In the two floors below, people work out in a gym. The enigmatic round tower looks empty.

The feature was a late addition to the shopping centre, which opened on the site of the former Jervis Street Hospital.

In 1996, the council granted developer Stamshaw Limited permission to erect a new entrance sign outside the centre on the corner of Upper Abbey and Jervis Street.

Included by Stamshaw in its application was this feature, listed only as a “tower”.

All over the city, there are unexplained features, and Quigley loves to try to fill in the gaps around what they are, she says. “They are these little Dublin mysteries.”

She has labelled a turret on the roof of Noblett’s Corner at the top of Grafton Street, “Dublin’s last town crier’s office”.

She has bothered the National Museum of Ireland on Kildare Street by email asking about an alleged series of mosaics, which she says are obscured by mobility ramps. “I asked if they had photos of them. But they said they didn’t have any in the archives.”

But the truth could spoil the magic of these places, she says, rising in a lift to the first floor of the Jervis car park. “I almost don’t want to know that.”

“If a place like the National Museum sent me back pictures of the mosaics, I probably wouldn’t think about them anymore,” she said.

In her own work, she lets the motives of characters evade her. Take a recent piece, “The Smoothest Stones Are Under The Water”.

A woman’s hair seems to form a pool of water, from which fishes emerge. In the top right, a pale hairless character is entranced by an anthropomorphised tree with a human face and outstretched branches.

“I’m still not sure what is going on with this interaction,” she says.

Quigley ventures deeper into the centre. She wanders up the ramps in the echoing car park as the faint sound of Miley Cyrus’ “Wrecking Ball” plays in the distance.

Everywhere, there are “no access” signs. Somebody has sketched out an electricity circuit on a concrete pillar, and by the keyhole of one door, instructions to use “key twelve” are jotted down in black marker.

Eventually, she reaches a window overlooking the city. It is covered in criss-cross bars. And in the very corner, she laughs upon seeing the “lighthouse”.

It is empty, save for four lights, which are fixed to the ground and pointed upward. There isn’t a clear way out there, she says. “So close.”

For several moments, she appears disappointed. But there is a door into it that she hasn’t yet been through, she says. “I feel reinvigorated by this now.”

There is still the question of why it exists, she says. “Let me see the building plans. Who said let’s put this up there? Why did they put it up there?”