What’s the best way to tell area residents about plans for a new asylum shelter nearby?

The government should tell communities directly about plans for new asylum shelters, some activists and politicians say.

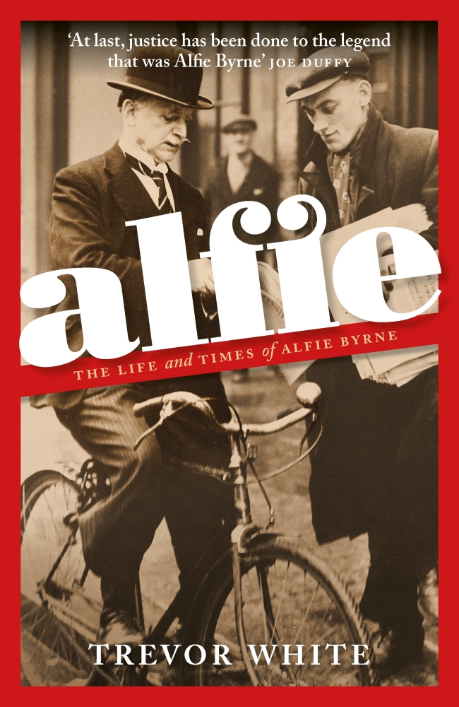

Trevor White’s new biography of Alfred Byrne tells the story of “the most popular Dublin-born politician of the twentieth century”, in all his complexity, writes historian Donal Fallon.

The office of lord mayor of Dublin has been held by figures as politically diverse as Daniel O’Connell, Benjamin Lee Guinness and trade unionist Joseph Nanetti (who made an appearance in James Joyce’s Ulysses).

There have been trailblazers (none more so than Kathleen Clarke, the veteran republican activist who became Dublin’s first female lord mayor) and the occasional villain.

Yet in the long annals of the position, only one person has held the office on ten occasions, nine of them consecutively. Alfred Byrne, known in his day to Dubliners young and old as just “Alfie”, is rightly described in Trevor White’s biography as “the most popular Dublin-born politician of the twentieth century”.

This new work, which draws extensively from Byrne’s archival papers, is an important and not uncritical biography of a politician who appeared to be an unsurpassable opponent to others in Dublin municipal politics.

It would be wrong to suggest that Byrne was universally popular, but what politician is? Take Eamon Dunphy’s autobiography, The Rocky Road, in which Byrne is described as “a small man dressed in Edwardian clothes, who doled out sweets and pennies to the children of Jackeens … My mother and father despised him. In their view, the sweets and the pennies were no substitute for proper representation.”

In a similar vein, he is remembered in one Bureau of Military History Witness Statement as a “tin god”, a glorious old insult meaning “a person, especially a minor official, who is pompous and self-important”.

Still, a political career that included stints as a Westminster parliamentarian, a TD, a senator and such a lengthy stint as first citizen of Dublin required the support of the masses, something Byrne had in abundance.

Byrne became synonymous with his rather distinct style, with White noting that “the top hat lent height, while a cane is always a useful symbol of authority. Costume and charm were essential assets in the seduction of Dublin.”

Despite appearances, Byrne was a product of working-class Dublin, the son of a docker raised amidst streets that Sean O’Casey described as “long haggard corridors of rottenness and ruin”.

Leaving formal education at a young age, he learned everything he knew about the city and its people from his stints in public houses, firstly as a young barman and later as a bar owner. A teetotal publican was sometimes a source of amusement in the press.

For the most part, Byrne enjoyed a positive relationship with the fourth estate, making seven appearances on the front of the influential Dublin Opinion magazine.

As a politician, Byrne masterfully presented himself as being free of any ideological bent. Of course, there is no such thing as an “apolitical politician”, and Byrne’s politics could best be described as a mix of constitutional nationalism and social conservatism.

First elected as an MP in 1915, he was swept aside in the 1918 general election, which was dominated by the Sinn Féin party, and which became something of a referendum on the question of Irish nationhood, following on from the Easter Rising.

Another publican, Phil Shanahan, took the Westminster seat on that occasion. Shanahan’s Monto-based pub has been described beautifully by historian Michael Foley as “a playground for adventurers, crooks and acute observers of the human condition”.

Despite losing out to the changing winds in revolutionary Ireland, Byrne managed to salvage and build a political career. He won the respect of many separatists by visiting interned republicans in Frongoch after the Rising, but it was by focusing on the day-to-day issues of Dubliners that he won most appeal in the capital in the years during and after the revolution.

The Belfast Newsletter described him as something of a master local politician: “What he stands for is difficult to say; everybody agrees that he is a ‘decent sort’ and all classes give him their votes.”

Byrne wasn’t merely a showman who wandered the streets of Dublin shaking hands and distributing sweets to the children of the metropolis as some simplistically choose to remember him; White points towards his highlighting of the shameful industrial-school system, something he was vocally critical of.

On one occasion, a man wrote to Byrne of how he “was beaten with the catoninetails for using tobacco, I had scars twelve inches long on my back for three months. I still carry a hunch on my back from that flogging.”

Such reports clearly impacted on the lord mayor, but those who controlled the rotten system merely urged an end to the “Mansion House mummery”, while the Evening Mail insisted that “in an institution they will have a much better chance of growing into useful citizens than if left to run wild through the city and suburbs”.

Any biography of Byrne must acknowledge the unsavoury company he sometimes kept in the 1930s, when a rabid anti-communism swept the city, culminating in Connolly House on Great Strand Street being almost reduced to ruins by mob violence.

White notes that Byrne was “sympathetic to some of the aims of fascist movements that emerged in Europe in the 1930s, because of his Catholicism and his antipathy to communism”, but challenges the idea that Byrne harboured any kind of anti-Semitic feeling.

White is correct that Byrne enjoyed friendly relations with Dublin’s Jewish community, including Louis Elliman, described as “the most prominent Jewish citizen in Dublin”. Byrne’s anti-communism was reflective of the time, and White also acknowledges Byrne’s support for Eoin O’Duffy’s haphazard escapades on Franco’s behalf in the Spanish Civil War.

If it is true that history is written by the victors, the Spanish Civil War is surely an example of the very opposite ringing true, and history has certainly been kinder to those who defended the Spanish republic than those who fought to overthrow it.

All of this is an uncomfortable dimension of the Byrne story, but it is well dealt with here, and is proof that White has not set out to write a hagiography, but rather a biography that gives an idea of the complexities of Byrne’s character.

Byrne’s support for censorship – White calls it an obsession – is also acknowledged. He supported the draconian censorship bill of 1928, a piece of legislation that so infuriated George Bernard Shaw that he thundered, “having broken England’s grip of her, [Ireland] slopes back into the Atlantic as a little grass patch in which a few million moral cowards are not allowed to call their souls their own by a handful of morbid Catholics”.

White writes with great wit and style, but it is his use of the words of others that sometimes bring the text to life, and great credit must go to Paddy Byrne for donating his father’s papers to the Little Museum of Dublin in 2015.

These primary sources add another layer to the story beyond just municipal politics, providing insight into how Dubliners viewed Byrne and his role. He was inundated with letters seeking assistance with employment, as well as Dubliners more than willing to give their opinions on the running of the city. That they felt a connection to the lord mayor is undeniable.

Regardless of how one views Alfie Byrne, his longevity in politics alone makes his obscurity in recent historiography and popular consciousness curious. As White notes, “for thirty years, he was one of the most popular men in the state. In twenty-six public elections, he was elected twenty-five times.”

Few politicians anywhere in the democratic world can boast of such a record. Perhaps some of the forgetfulness around him is due to the image Byrne cultivated of himself, and it is certainly true that “Byrne conspired in the idea that he was jokey figure. It was part of the brand.”

In truth, despite appearances, he was someone who understood the ins and outs of the Irish political system better than most. Whether one chooses to see him as a “tin god” or as a champion of the city, he deserves to be studied, and White’s biography is a very welcome addition to the bookshelves.

Alfie: The Life and Times of Alfie Byrne, by Trevor White (Penguin, 2017)