What’s the best way to tell area residents about plans for a new asylum shelter nearby?

The government should tell communities directly about plans for new asylum shelters, some activists and politicians say.

The pandemic and city’s housing crisis have meant that artists aren’t so often in the same place, and can’t so easily drop in to each other’s studios to chat.

Olivia Normile hadn’t seen the box, sitting innocently on the table in the centre of a table in her studio in the Complex on Arran Street East, since last summer.

Last Saturday, she gingerly lifted the cardboard flaps and peered inside.

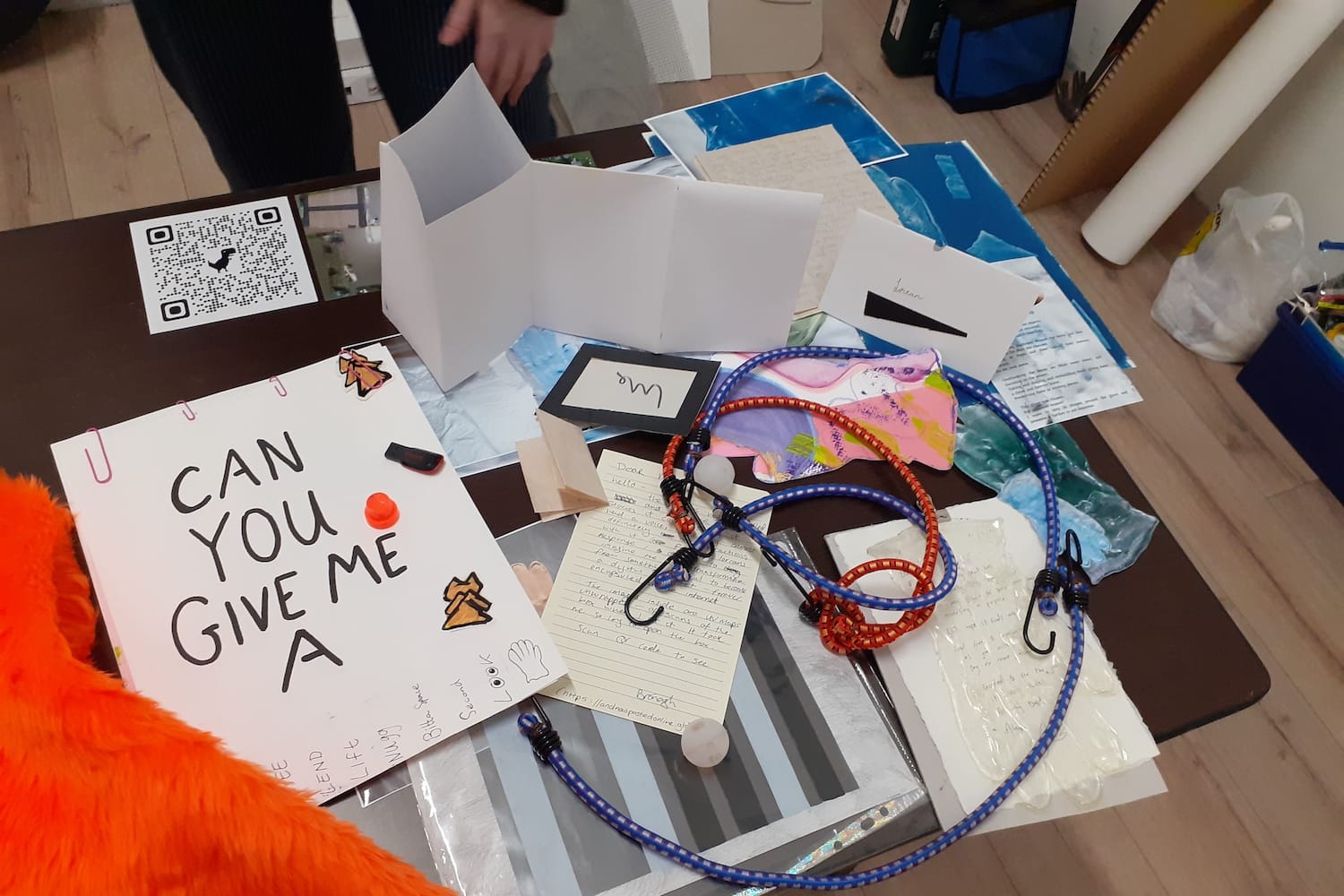

She pulls our scraps of folded paper, a ping-pong ball, neon-orange fuzzy fabric, two aerial photographs, a handful of cable ties looped together, and a see-through resin glove stapled to a clipboard.

Through the resin is a note signed by artist Alex Keatinge.

“We all wrote each other little notes,” says Normile, lightly lifting another letter out of the box and placing it to the side.

The resin glove was the first artwork in Deliverables, a collaboration-chain project that Normile and five other artists dreamt up in April last year.

Collaboration can strengthen and further the work of an artist, stopping them from staying in one place, says Normile.

But the pandemic and city’s housing crisis have meant that artists aren’t so often in the same place, and can’t so easily drop in to each other’s studios and stumble into conversations about working together.

“It can be isolating,” says Normile, which is why the group came together to start Deliverables.

The see-through resin glove was the first whisper of her own art practice, one that the artists could reflect on and send responses to, in a chain throughout the project, says Keatinge, in a text on Monday.

The project was a first step for the artists to get a sense of each other’s current work, materials, themes and ideas, she says. “What is catching our eye at the moment.”

A glove had been lying around her studio, she says, but it felt like it could be like a sense of touch. “It felt right to send it out to other artists to find its meaning or interpret it in their own way.”

In April, she posted the resin hand on the clipboard with the note to Montreal, where it reached artist Ellen O’Connor.

“Feel free to manipulate it as you wish,” Keatinge had scrawled under the resin.

In her studio in The Complex, Normile pulls from the box a long series of paintings, scans, prints and sketches of gloves. The others in the group, whenever they’d received the box, had mimicked the helping hand.

Normile had been the fourth in line to get the box. She created an audio file, and a squiggly line on a square piece of cardboard.

“I was thinking about the lack of physical gesture, and you know, what is that without a hand, maybe it looks like that, maybe it’s the motion,” she says, tracing her finger along the line, which could also say “we” or “me”.

It’s an unfinished idea – as the entire contents of the box is, she says. “This was an exercise for us. These are more tools rather than finished works.”

Normile hadn’t met any of the other Deliverables members until she collected the box from Daire McEvoy on a hot summer’s day.

When she got home, she didn’t open the box straight away. “I was kind of staring at it for a while,” she says, remembering.

She wanted to be in the right headspace to see the work of her fellow artists, she says. “Really make sure I was soaking it in.”

Before, Normile collaborated with others because she shared a studio with them or they were friends already, she says.

Those small collaborations are so essential, she says. “Let’s make a little print book together, let’s work on a drawing together.”

Art in isolation is tough, she says. “It’s so hard to get any sort of perspective on your own practice, to push your work, to show anyone your work.”

But “for so many people that you know, might not have a studio space, might not be able to see people in the city centre, because wherever they live might be isolated”, she says.

McEvoy says that in art college, lecturers encouraged him and other students to engage in one another’s work. To chat, get a fresh view, he says.

Now, working in a garden shed-turned-studio in Balbriggan, he sometimes misses working in a communal studio space. “Not that it’s lonely, but you can get lost down rabbit hole.”

Since graduating, he’s found there isn’t much studio space to rent and applying for grants can be difficult, he says. “You’re basically fighting other artists in applications in order to get a space.”

Normile says the box, in a way, reflected that experience that had been heightened by the pandemic.

“A lot of us were thinking about the journey, the silent, lonely journey that the box would have made,” she says. “It has such a presence as well, which kept coming up for all of us too.”

The Deliverables group is plotting an exhibition in Pallas Studios in The Coombe on 14 April, exactly a year since they started.

Although it won’t contain the work of the box, it has been the starting point for many of them in creating a cohesive collection, having spent so much time thinking about the work of five other artists, says Normile.

Once the box was finished, full of their scraps of art, their weekly discussions became more intense as they were more comfortable with critique, she says. “Pulling things out of each other, pushing each other.”

Normile says that, for an artist, working collaboratively and by yourself is like speaking two different languages.

“I really have to pay equal attention to their work,” she says, “because some of it is coming from me as well, and some of their work is in mine.”