What would become of the Civic Offices on Wood Quay if the council relocates?

After The Currency reported the idea of the council moving its HQ, councillors were talking about and thinking through the pros and cons and implications.

Lynch stood up to pimps and gardaí, fought stigma and campaigned, calling for respect, equality and safety for sex workers. She was murdered in 1983.

In a city cemetery, a blank monolith sits between two gravestones.

On Friday morning, two burnt-out candles, a vase filled with yellow leaves, and a tiny winged-angel sculpture rested in front of the monolith.

This is the grave of Dolores Lynch and her mum, Kathleen.

Dolores Lynch worked for herself selling sex in Dublin city for about 15 years, never for a pimp, she told journalist Geraldine Kennedy in 1979.

She stood up to other women’s violent pimps and hostile gardaí, fought stigma and campaigned, calling for respect, equality and safety for sex workers.

In May 1976, Lynch’s evidence in court had landed John Cullen, a city pimp known for his violent temper, in jail for three years for assaulting her and other women.

Cullen’s dad had died when he was nine, causing him to unravel, according to a memoir by his ex-girlfriend, Lyn Madden.

His mum put him in Upton Industrial School in Co. Cork to set him straight, where he faced physical abuse from members of the religious order who ran it, the book says.

When Lynch was due to testify in court against Cullen and another guy, Cullen beat her up at a restaurant on Baggot Street and told her he’d kill her if she did, according to Lynch’s testimony to the Gardaí, quoted in a book by former chief superintendent John Courtney.

Cullen ended up in jail. “Dolores had been brave to stand up to a vicious, dangerous man, but he never forgot or forgave what she had done and swore he would kill her for ‘squealing’ on him,” Courtney wrote.

On 16 January 1983, Cullen slid a firebomb through the window into Lynch’s home in Blackpitts, 15 Hammond Street. Lynch’s mother Kathleen (61) and aunt Hannah (67), died in the fire. Lynch herself, severely burned, was taken to the hospital.

At that point she worked as a cleaner at St James Hospital. She told a priest to let her boss know she couldn’t clock in for Monday just hours before she died from her wounds, wrote the priest, Fr. Pat Mulcahy, in the Evening Herald at the time. She was 34.

Cullen was done for murder and sentenced to life after Madden, his lover, who also worked for him, told the court that she watched him set Lynch’s home on fire and quickly went into a witness protection programme. She eventually left Ireland.

Forty-two years after Lynch’s murder, some campaigners for sex workers’ rights say Lynch’s hopes of wiping stigma and safer sex work are still unfulfilled.

“Here we are in 2025, and it’s not that different,” said former politician and civil rights campaigner Bernadette McAliskey by phone on Friday.

One afternoon in 1979, Lynch turned up to the Irish Times offices with a petition to the then-Minister for Justice, Fianna Fáil TD Gerry Collins.

It was signed by most of the 70 sex workers in Dublin at the time, wrote Geraldine Kennedy, the newspaper’s former reporter and future editor, in a 1983 Sunday Press article.

“She wore a black velvet jacket, black patent high-heeled shoes and a red dress,” Kennedy wrote.

They went to Bewley’s café. Lynch carried the mark of 26 stitches on her face, traces of an attack by another woman’s pimp, she told Kennedy. “The scars made her look at least 10 years older.”

She met Kennedy as a spokesperson for Dublin’s “street girls”.

Her petition was calling for an end to “what they saw as the discrimination and injustice against them in the courts”, wrote Kennedy.

Lynch had said she wanted to spotlight the case of Teresa Maguire, a former sex worker who was violently killed in the city, but the assailant got off without serving jail time, Kennedy wrote. She told Kennedy how routinely women were assaulted.

“We want to stress that it’s not the retributive aspect of the (Maguire) case that concerns us but rather its implications for the safety of the girls who make their living on the streets,” said Lynch’s petition.

“The action we are taking is due to fear for our lives. We have never written to a Minister before,” it said.

She’d tried to meet Collins four years earlier, but he wouldn’t meet her, the article says. She’d written to the President too – at the time Patrick Hillery – who also never replied to her, the article says.

Then-TD John Horgan of Labour had raised the issue at the Dáil, but the minister had told him he couldn’t comment because Maguire’s case was ongoing at the court, it says.

Then Lynch wrote another letter.

Her letter said that the minister was just avoiding them, using the court case as an excuse. “This is typical of the attitude of society in general.”

In December 1974, Lynch had accused Edward Hayes, a garda, of assaulting her and stealing her money at Herbert Place where she usually hung out to sell sex, shows a clipping from a 1975 Irish Independent article.

After just five minutes of deliberation, the jury cleared the garda of the charges, the article says.

The garda had told the court that on the day of the incident, he’d agreed to let Lynch into his car as a “stupid joke” when she kept trying to draw him in as a potential client. That Lynch had then wrongfully accused him of taking her £20, he’d said.

He had used his “closed fist” on her face to push her away, Hayes had told the court.

Peter Maguire, the garda’s lawyer, said it was true Lynch never changed her story “in evidence and in cross-examination”. But he asked the jury to consider that she had prior convictions and framed her as a vindictive woman angry that a guy wasn’t interested.

“This woman saw in the defendant her fourth client and she was raging when he told her he didn’t want anything to do with her,” Maguire said.

Four years after that, in November 1979, Lynch sat before students at what’s now known as the University of Galway to participate in a debate organised by its Political Discussion Society, introduced as “Ms Dolores X”.

She was debating with Bridie O’Flaherty, then a Fianna Fáil councillor. An RTÉ recording of the meeting obtained from its archives says O’Flaherty and others “confront a Dublin prostitute”.

In that meeting, Lynch tries to highlight Gardaí hostility, too.

It all comes to a head when O’Flaherty asks her why she still sells sex if she doesn’t think it’s a great job. Lynch tries to explain that it’s hard to move on.

“I mean, I had a job, but a guard went to my superiors and said I was a prostitute,” Lynch says. She sounds calm.

Her boss told her they didn’t feel the way the guards felt, but she left because she was embarrassed, Lynch said. “I couldn’t face them, so I said, ‘take my notice’. I felt so degraded and so let down.”

Linda Kavanagh, a spokesperson for the Sex Workers Alliance Ireland (SWAI), said last week: “Jesus, I mean, that could be a testimony of a sex worker today.”

Kavanagh says sex workers’ relationship with the Gardaí is still thorny and filled with distrust.

Lucy Smyth, director of UglyMugs, a non-profit with an app for improving the safety of sex workers, says that, consistently, fewer than 1 percent of their users who had submitted reports of assault said they reported them to the Gardaí, too.

Kavanagh says the cops would often book sessions as clients to carry out welfare checks on sex workers, and that further erodes trust. “So, they’re lying to get access to sex workers.”

People’s experiences of the welfare checks are mixed, but that approach freaks some workers out, she said.

A spokesperson for An Garda Síochána said it doesn’t comment on third-party remarks.

During welfare checks, officers provide relevant contact details, including for Garda liaison officers and HSE’s women’s health services to sex workers.

These checks also aid in identifying those “who maybe being sexually exploited or trafficked”, they said.

Though they’re conscious of the fact that it’s not the case for everyone, the spokesperson said.

It “assures any person involved in the sex trade that An Garda Síochána is here to listen, and will treat any report of a crime against them very seriously and sensitively”, they said.

Central to debates around the safety of sex workers and their relationship with the Gardaí is disagreement about current laws regulating sex work and whether they are enough to reduce danger and keep people safe.

Under current laws, it’s not illegal to sell sex, but it’s illegal to buy it.

Some sex workers have long argued that the current approach still criminalises their work and marginalises them.

Under current laws, women can’t legally work together to enhance safety because that counts as brothel-keeping and would be illegal.

There’s evidence pointing to the shortcomings of the current model.

A 2022 report by a researcher at the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE), the upshot of 210 formal interviews with sex workers, found that 96 percent of participants said the Nordic model – which makes the purchase of sex illegal, as in Ireland – made them feel unsafe and vulnerable to exploitation as they try to protect their clients from getting done for buying sex.

It contributes to housing insecurity, making it harder for sex workers to rent because their landlords can be accused of pimping. It can get migrant sex workers on precarious immigration statuses deported, too, it says.

“The findings show that the majority of interviewees … support removing criminal penalties related to the sex trade so that sex sale can be organised without punity,” the report found.”

Another study shows that in New Zealand, where buying and selling sex is legal, workers’ relationship with the police has improved.

A November 2024 research published in the International Journal of Gender Studies, which examined sex workers’ experiences of stigma in Ireland, New Zealand and Scotland, found that those selling sex in Ireland and Scotland felt less comfortable disclosing their work to healthcare professionals.

Some see it differently and support the Nordic model, pointing to other studies and sources.

A spokesperson for Ruhama, a charity fighting sexual exploitation and prostitution, said current laws are meant to tackle demand while supporting women pushed into selling sex by complex societal factors like poverty, education and migration.

The Nordic model is “effective in attempting to combat the demand for sexual access to women and girls, which is one of the root causes of prostitution and human trafficking for sexual exploitation”, they said.

A larger sex trade means more sexual violence, pimping, and trafficking, they said.

They pointed to a recent European Court of Justice ruling which said the Nordic model’s interference with sex workers’ right to private life was not disproportionate

Amnesty International has criticised that judgment as a “missed opportunity” to acknowledge the harm caused by criminalisation of sex work.

Demand for sex workers was another issue that cropped up in the University of Galway debate in 1979.

Lynch argued that sex work is a service, and there’s always demand for it on the streets.

Some guys just want to talk; some just want to have sex. Some guys who just want to talk feel like they ought to have sex, too, she said.

“It must be a social need if the demand is there,” Lynch said.

McAliskey, the civil rights campaigner in Northern Ireland, said nobody’s out there trying to wipe out the demand for alcohol.

“It’s nice to say there shouldn’t be any demand,” she said. But that’s not how the world works, McAliskey says.

“And if you want to make the world a better place for everybody, then everybody should have equal rights to protection.”

To be clear, McAliskey said, she is against all kinds of sexual trafficking and exploitation, but she knows women who aren’t coerced by a pimp or trafficking rings.

If their workplace weren’t criminalised, they would’ve been seen as freelancers or small business owners, she said.

Suggesting that no woman would be willing to sell sex is implying they lack agency, she said.

“You know people who stand in abattoirs in freezing temperatures, slaughtering animals? Do you think they would do that if they could get other work? But nobody calls that coercive work,” McAliskey said.

Sometimes, people simply sell sex because it pays better than lots of scraping-by jobs that they can get, and those people need and deserve protection, she said.

The LSE report says that the discourse conflating commercial sex and sex trafficking doesn’t line up with the experiences of sex workers.

Among its pool of 210 sex workers interviewed for the research, only 6 percent considered themselves to have been trafficked or coerced to sell sex, it says.

Lynch got into sex work through a woman friend, she told the meeting at Galway University.

“I was short of money for a dance, and I wouldn’t ask at home because I had had an argument,” she said.

Her friend said she knew a way of making money and she could show her. Soon, she slipped into it, too, said Lynch.

She’d told Kennedy, the Irish Times reporter, that she was glad that a guy didn’t get her into sex work.

She didn’t like men because of the way she’d watched some of them behave, she’d told her.

Lynch’s dad had raped her, wrote Courtney, the former chief superintendent, in a book that explores her murder case.

Lynch had been nervous about travelling to Galway for the meeting to talk to “intelligencia in a university”, she’d told Kennedy.

O’Flaherty, the Fianna Fáil councillor who was debating her that day, said buying and selling sex is immoral and unchristian.

“Wrong in any Christian circumstances. And I mean, I’m not saying Catholic, I’m speaking of the Christian view,” she said.

But Lynch was religious, too. The memoir by Madden – Cullen’s ex-lover who turned him in – says that when they worked along the canal, if they went to the Legion House to get a cup of coffee in the cold, “Dolores was the only one willing to kneel down to say the rosary with the nuns.”

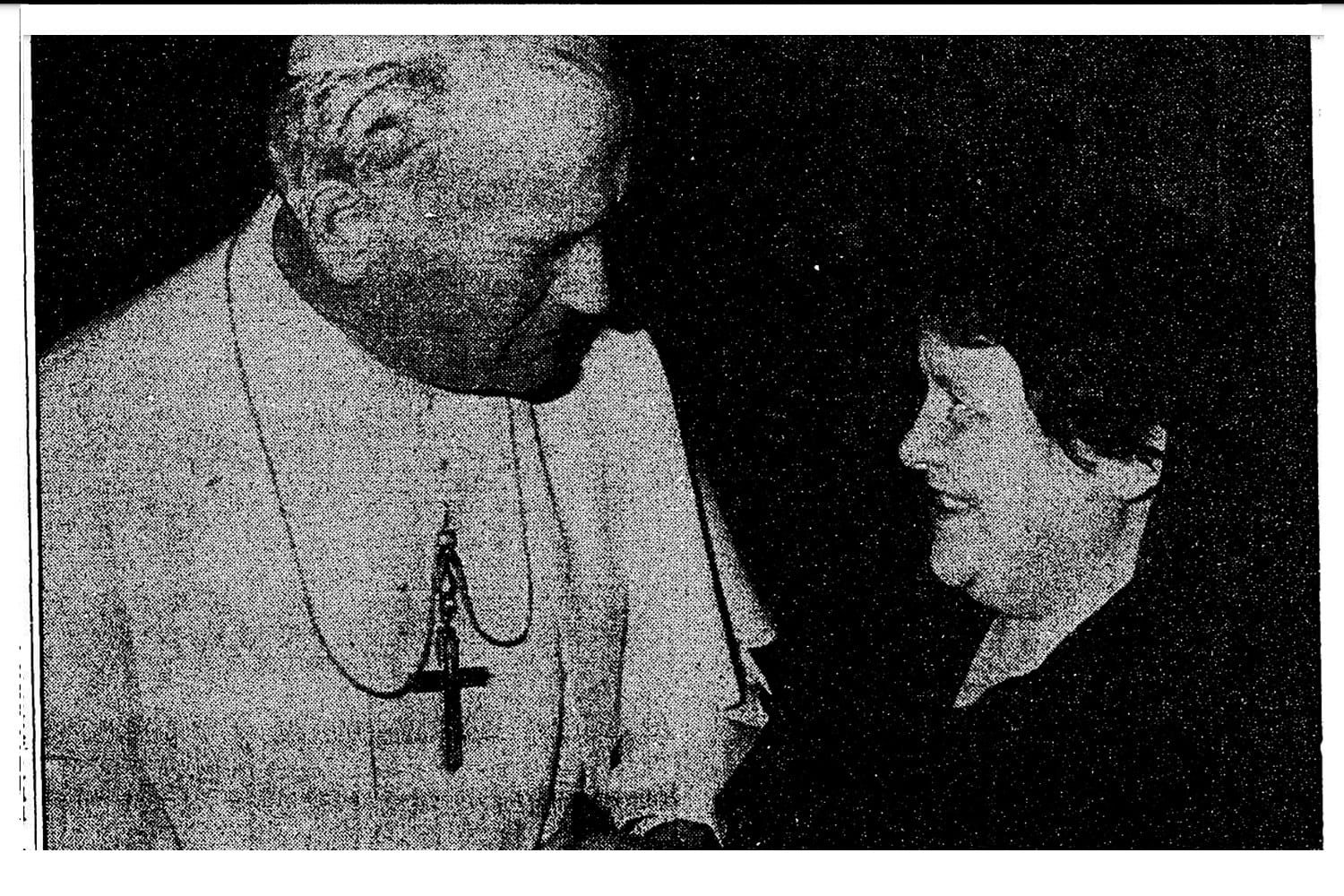

Once she’d stopped selling sex, she’d written letters to Pope John Paul II, who invited her to the Vatican. They met, and Lynch kept a rosary and a photograph as souvenirs.

The photo shows a frail Pope clasping Lynch’s hands, who’s grinning and glancing up at him.

Kennedy’s article says Lynch’s only male friend, a priest, had told her to leave the country when she began campaigning for sex workers’ rights.

“He said that she shouldn’t be publicising the whole business of prostitution,” it says.

He’d called her possessed by the devil. “I realise Dolores that it’s not you that is really telling that filth to the people – it’s the devil in you.”

She was shattered, it says.

Kavanagh of SWAI says the weight of stigma felt by Lynch is still felt today.

O’Flaherty told the meeting at the University of Galway that she wants the government to root out “whatever prostitution is going on in the country”.

Lynch said she and other women on the streets wanted to be treated with respect and have equal rights.

“Walk out onto a street in around the Dublin area, and you know, […] you will see for yourself that the demand is there. It must be a social need if the demand is there,” Lynch said.

But “We’re completely discriminated against by police, courts, and everyone, you know, public in general, and we want to try and put a stop to this,” she said.