What would become of the Civic Offices on Wood Quay if the council relocates?

After The Currency reported the idea of the council moving its HQ, councillors were talking about and thinking through the pros and cons and implications.

As the neighbourhood changes, what can this grey monolith show us about the connection between people, buildings and the place they share? asks an architect.

The identity of the place we call Phibsborough is made, in part at least, by the existence of a pre-cast-clad concrete office building, carpark and shopping centre that hangs out on the corner of Phibsborough Road and Connaught Street.

It is difficult to think of another borough of Dublin that is so strongly identified with a single building. Nor are there many communities of residents who have been so galvanised around a single object of 20th-century architecture.

Theirs is an active concern for the current state and future development of the shopping centre itself, a relentless energy that has fueled years of debate and events about the general built environment of Phibsborough.

The 1960s building was described by journalist Frank McDonald as a “dreary landmark” in 1985, and continues to attract negativity. You encounter residents and visitors who love and loathe the building.

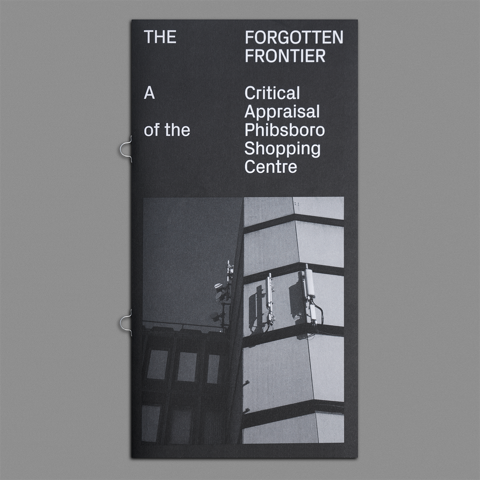

In November 2017, the story-so-far of this building, Ireland’s first ever combined shopping and office centre, designed by architect David Keane, was recorded in a beautiful zine designed by Eamonn Hall of Phibsboro Press.

In the zine, Cormac Murray, in his brilliant biography of the building, reminded us of historian Pat Liddy’s words in the Irish Times in 1987 that the Victorian charm of the place had been,”plundered … in the name of progress”.

Twenty years later, journalist Olivia Kelly wrote that the 31-metre office tower is “often cited as one of the ugliest buildings in the city”. Nevertheless, it is a source of aesthetic and formal fascination for photographers, architects, and artists too – and its image continues to be shared on social media.

This love-hate controversy has helped to ensure that, more than most buildings, the shopping centre has remained present in the minds of local residents and the city, even in times when the centre was in no immediate danger of change.

Indeed, on the night of the zine launch, which was held in a room across the road from the centre, it was clear that the centre was no longer a passive object, redundant over there, but instead, against the odds, it had become an active participant in the social, spatial and community life of Phibsborough.

While we had, in theory, gathered to toast and launch a zine, we were also in a way there to pay our respects to the cover star. It was, you see, understood by those in attendance, that as the building’s physical form and nature was about to change forever, so too was the identity of Phibsborough itself.

Recently sold and bought again, the shopping centre – a challenging site to develop – is the subject of a live planning application. The decision to grant planning was recently referred to An Bord Pleanála.

This means the centre’s future is soon to be the subject of a debate – this time, in the form of an oral hearing – starring those who, bravely, dare to imagine a future life for the development-dowry which the centre commands, and those who, among others, seek to protect the formal and visual integrity of the grey-grid of the 409 panels that wrap its bony, grey frame.

What is clear is that something will soon happen on this site. This entire place is set to change. The questions arise as to how, for whom and by what means will this place be made and remade? If just one building, the shopping centre, has acted as a concrete community anchor for initiating change, what should or could any new buildings do for this place?

Few buildings of architectural note have been constructed in Phibsborough since the shopping centre. The borough continues to have many empty sites, several vacant buildings and a rather dilapidated main street.

This part of Dublin has been long neglected. This is in part because it falls between political and electoral responsibilities and has been cut adrift from place-specific planning guidance. There has been little developmental focus or investment, and a number of large-scale projects – such as new housing on the old Smurfit site – have yet to materialise.

However, things appear to be changing. In early 2018, Phibsborough welcomed its first building of clear architectural intent in very many years. The two-storey brick building is not on main street, rather it is found at Phibsborough’s northern edge. It is a crèche.

The crèche is not unlike the shopping centre in as much as the building has a number of streets to contend with, meaning the building has several facades. Rather unlike the centre however, this building really does set out to belong and fit in; building lines of the shops and houses beside are held, the familiar red brick of Dublin 7 is used; the heights and proportions of the neighbourhood buildings are studied and respected.

Yet, the architects rather skillfully riff on all of these local characteristics. So as the building forms a straight edge to the street, the walls that form the rooms inside for the children peel and curve back; the bricks are flat and traditionally bonded on some elevations, but woven-brick screens are also made, some solid, some void; bricks are pushed proud of curved walls to provide depth, texture and shadow, and all of this is witty and pretty and clever and cool.

Today, it appears more buildings are set to follow. In the borough, white planning notices abound, something will almost certainly happen on the shopping-centre site, and Dublin City Council and Bohemians are moving, albeit slowly, toward the redevelopment of the stadium for football and general community use. Projects of significant scale and impact are on the horizon, many new places are about to be made.

In architectural terms, the shopping centre and the crèche appear to present opposite attitudes to place. On a site famously observed first from the air in a helicopter by the developer, the centre appears to have just landed in its context, disrupting what came before, stubbornly insinuating itself.

The crèche however, emerges from the ground up, seeking local acceptance, and strategically uses scale, form and materials, so that at first glance the building appears as if it might always have been there.

What both buildings have in common, however, is that each emerges from the dominant and prevalent culture in which each has been designed and constructed.

The built, material form of the shopping centre bears witness to a once strongly held belief in system building, concrete and prefabrication above all else, even at the expense of the place in which such buildings were constructed.

The council once encouraged developers to build offices in Phibsborough to relieve congestion in the city centre; the tower was a form that, in the 1960s, reflected prevalent political ambitions and confidence in the future.

Unconventional in form perhaps, the crèche reflects our internationally acclaimed, creative ethos of critical-regionalism, where buildings emerge out of – but, let’s be honest, are also often expected to respectfully sit back down into – the material, grain and abstract atmospheres that are identified by an architect as somehow being emblematic of that place.

Your building can stand out, but not too much; you can be an individual, but our terms and conditions will certainly apply. There is much anecdotal evidence that architects and those who commission buildings are forced to employ such aesthetically driven strategies to get any building that has ambition through a thirsty planning system that seems all too easily sated by an often bitter, liquid banality.

In Phibsborough, a place poised to rebuild itself, surely it is time to check where local desires and intentions can find their place with regard to the often external concerns and preoccupations of wider cultural, creative and political forces, be they brutally radical or creatively conservative?

The idea of “place-making”, mentioned many, many times in the recently published Project Ireland 2040: National Planning Framework, is very much part of current political ambition and strategy.

It is also a term used liberally in Dublin City Council’s Development Plan 2016-2022, the current plan governing the socio-spatial future of Phibsborough. What “place-making” is exactly in an Irish context is not obvious from reading these documents.

When you close your eyes and think about it, place-making seems like a fine idea. The term seems broad, but it also implies something very local and specific indeed, perhaps just what we need to move forward.

However, when you read in Project Ireland 2040, with regard to the Eastern and Midland region of Ireland, that the, “_region’s most significant place-making challenge will be to plan and deliver future development in a way that enhances and reinforces its urban and rural structure and moves more towards self-sustaining, rather than commuter driven activity, therefore allowing its various city, metropolitan, town, village and rural components to play to their strengths, while above all, moving away from a sprawl-led development model”_, the term “place-making” is rendered impotent and the language presumably intended to clarify, only confuses.

While it should be of concern to all of us as citizens that our state is adopting a term that remains undefined yet is profound in its implications, the meaning of the term should undoubtedly be of urgent concern to the profession of architecture.

Without the demand of evidence-based definitions of what place-making is or hopes to achieve in a specific Irish context, the danger is that architecture will be a passive participant in the socio-spatial cleansing of the everyday reality of our places in the name of the ideology of a rather generic progress.

Without a conscious elaboration of our dominant architectural ethos, architecture could be instrumentalised in the name of place-making to deliver award-winning, beautifully acceptable rooms, replete with all the fine details of an appropriate and real-estate friendly nostalgia.

Without the profession of architecture finally acknowledging that all of us – trained architect or not – make and remake our interior and exterior built places through a series of complex, messy, creative, awkward and often slow processes that are social, spatial, material and temporal, our professional actions will only work to exclude our fellow citizens from the places we are meant to be making with them.

In Phibsborough, a single building has provoked a group to collaborate in and through the material, built and everyday reality of their place, fostering and sustaining their community. This person-building collaboration has directed their action when remaking their place.

It was surely not what the architect of the shopping centre intended by design, but it points perhaps to what architecture has to generously and graciously offer, when someone sees beyond the allegedly ugly skin and finds what is needed, what is useful to a place.