What would become of the Civic Offices on Wood Quay if the council relocates?

After The Currency reported the idea of the council moving its HQ, councillors were talking about and thinking through the pros and cons and implications.

“When you have regulation of the entertainment industry from 1935 it’s definitely outdated,” says Constantin Gurdgiev. “The social conditions which might have warranted the regulation no longer exist,” he says.

Reggae DJ Siobhan Conmy had big plans to open a live reggae venue in Dublin, and it all seemed to go smoothly – until she tried to get permission for dancing.

Conmy used to organise reggae events, along with Cristina Llarena, in the Turk’s Head on Parliament Street, drawing crowds of 2,000, she says.

When the Front Lounge, another bar just a few doors up from there, became available, the two decided to lease the building.

The overheads for a bar are huge, but they thought they had spotted a gap in Dublin’s dance scene. “We were going to transform it into a live reggae venue,” says Conmy. “That was my dream to have my own reggae bar.”

She knew she would still have to get a dance licence. “For people to dance on our premises you need a dance licence, separate to the music licence, and separate to the drink licence,” she says.

But she had no reason to think her application would be turned down. As soon as she started to advertise the bar as a live music venue, though, some neighbours objected.

It took her 10 months to get the dance licence. When she did, it came with the condition that they would hold live music events just three times per year, she said. “Our dream was shattered overnight when we realised we wouldn’t be allowed to play the live music.”

Conmy says the licensing system needs to be streamlined, so that when people sign a lease agreement they know what the bar is licensed for. (At the moment, each new operator has to go to court and try to get the licences they want.) Others agree that it’s time for the rules to change.

“When you have regulation of the entertainment industry from 1935 it’s definitely outdated,” says Constantin Gurdgiev an economist who prepared a report or the nightclub industry back in 2009 that called for licencing laws to be overhauled.

“The social conditions which might have warranted the regulation no longer exist,” he says.

All bars have a seven-day ordinary licence that lets them serve drink, says Conmy. But if they want to serve until 2am, bars need to get a €410-a-night extension.

On top of that, “to have music on the premises, you need a music licence, and to have people physically dancing then you need a dance licence”, she says. Three licences means three separate fees and three separate days in court each year to get them.

After Conmy and Llarena were hit with the dance-licence condition that they only have live music three times a year they changed course, and Street 66 is now a gay-friendly disco bar. “It’s a really nice vibe,” Conmy says.

But she hankers after her dream. “In the future there will be a [live] reggae venue in Dublin,” she says, but that would be somewhere else.

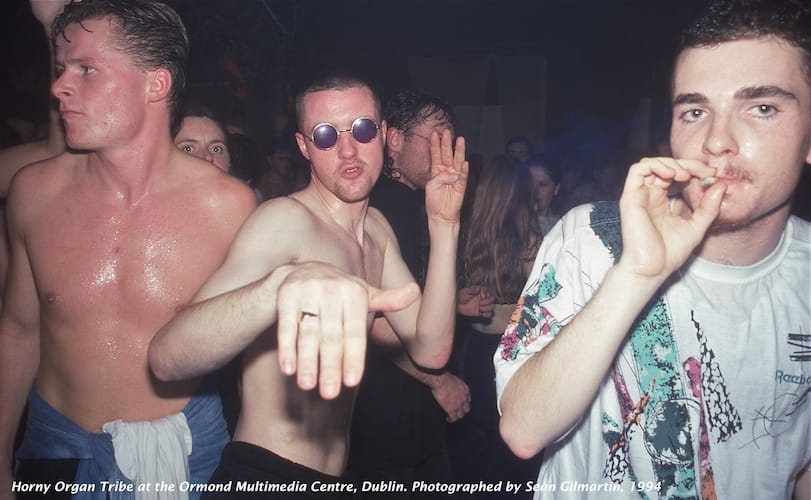

DJ Tonie Walsh says he has been complaining about Ireland’s archaic licencing laws for decades. In 1995, he was prosecuted under the Public Dance Halls Act 1935.

He was involved at the time in organising events in The Ormond, which is now the Morrison Hotel.

There was a clamp-down on dance music venues in Dublin, he said. Theatres, though, had an easier time of it with an automatic late licence.

Walsh was running a dance music event that included, in addition to DJs, walkabout performers and multimedia projections. That made it theatrical, he says.

But he and owner Paddy Dunning were taken to court under the Public Dance Halls Act of 1935. “We had to satisfy the police that the event had elements of theatre or performance,” he said.

“In the end of it all, they let me go and they fined Paddy the maximum amount they could which was £5,” said Walsh. He remembers a courtroom packed with venue owners worried about their licences.

“In many ways it shows you the ridiculous anomalies that exist in the law,” Walsh says.

Had the court accepted that the level of performance amounted to a theatre night, they would have been able to serve until late without needing a special exemption or a dance licence.

However since the judge decided the night (which he hadn’t seen) was not sufficiently theatrical, they therefore need both a special exemption to serve alcohol late and a dance licence to proceed.

Says Gurdgiev: “Defining theatre is impossible. There are forms of performance art which overlap with theatre.”

In the 18th century there was a distinction between opera and operetta, he says. Opera was considered art, while the popular form, operetta, was not. However, Mozart wrote operettas too, he says. Would anyone argue today that some of Mozart work wasn’t art?

Gurdgiev wonders how the Gardaí or indeed the judge were qualified to decide what could be classed as theatre.

“This indicates a gross overreach of the state into cultural, social and artistic engagements, and as a result, I think the state would be best served to get out of the business of doing these things,” he says.

The Public Dance Halls Act 1935 states that a licence must be obtained to hold a public dance regardless of whether or not alcohol is served.

The judge, when deciding whether to grant a licence for a dance, should consider “the character and the financial and other circumstances of the applicant”.

James Redmond, editor of Rabble magazine and director of the documentary Notes on Rave in Dublin, interprets this as meaning that applicants who share common interests and culture with judges are more likely to get licences.

“While the local GAA club might and does get a dance licence, I’m sure a group of clubbers that want to put on a 3am to 12 noon afterparty in a space probably won’t fare so well,” he says.

Redmond and Walsh both say that, down through the decades, they have seen that the dance laws are primarily enforced in relation to dance music or rave venues.

Says Gurdgiev: “When you have arbitrary enforcement, you undermine the credibility of the entire enforcement and regulation regime.”

A spokesperson for the Department of Justice says the 1935 act is still in full effect. “Of course, a licence is not required to dance, but a licence is required for premises (i.e. dance halls), whether licensed or not for the sale of alcohol, to which the public are admitted for dances.”

Applicants must show they are compliant with fire-safety standards, he says. Nightclubs and late bars must show they have the dance licence to apply for the special exemption to serve later, which means until 2:30am at the latest.

In other European cities, like Berlin, people often get together to host events where they dance and have fun, but they don’t sell alcohol, says Iarla Ó Muirthile of reggae duo the Rub A Dub Hi-Fi.

In the UK, many reggae gigs take place in the local community centre, he says, but he is unclear if it is it legally possible to do this in Dublin. “It is quite complicated and contradictory,” he says.

Solicitor Barry Lyons says that while there are multiple laws governing dance and music events and the situation is complicated, it should be possible to host dance events legally in Dublin without having a bar licence .

You don’t need to have an intoxicating-liquor licence to apply for a dance licence, says Lyons. “But there are all sorts of other things they catch you on,” he says.

Firstly you will have to convince an insurance company that it is safe for patrons to bring their own alcohol. If the venue isn’t usually used for dancing, you will have to deal with the fire officer, which can difficult, he says.

This will be easier if the building already has a fire certificate, but the requirements for your dance event might be different. For example, if it is ordinarily used as a community centre, it might need more fire exits to be used for a busy dance.

If you can get all those issues sorted, he says, you can inform the Gardaí of the event and then make your application, which should cost you around €500, including paying a solicitor, he estimates.

He thinks it would make sense to try. “The world has turned in the last 15 or 20 years,” he says. “The thought of a BYO event isn’t as absurd now as it was back then.”

Says Redmond, of Rabble: “If this whole Dance Hall Act was loosened up, if people were allowed to gather and dance together in BYOB spaces, you’d have a big income stream created for alternative and artistic communities in this city.”

The 1935 Public Dance Halls Act was introduced because the church was getting worried about jazz clubs taking off in Ireland, according to an article by Johannah Duffy, a researcher at the University of Exeter, in the Irish Journal of American Studies.

The priests “regarded this body-based music as a sexual and cultural threat”, she writes.

They were not opposed to dancing per se, but they insisted it be moved to venues over which they had oversight. The Gaelic League also campaigned against jazz.

Up until the Public Dance Halls Act 1935, traditional music and dancing had mostly taken place in houses, and the enforced move to dance halls is now thought to have accidentally contributed to the decline in traditional music.

“Country people found it hard to adjust, and to them dance halls were not natural places of enjoyment; they were not places for traditional music, storytelling and dancing,” writes Duffy. “They were unsuitable for passing on traditional arts.”

Says Walsh the DJ: “The government of the early Irish state was enslaved by a dodgy Roman Catholic ideology. It was about keeping people in their boxes.”

That same act governs public entertainment right up to today, and illegal afterparties happen because there is no legal option to stay out late, Walsh says. “The existence of these laws infantalises us,” he says.

Anyone who dares to organise a dance event without a licence should be warned: the punishment for not having the licence is a fine not exceeding £10.

[CLARIFICATION: This article was updated on 14 December at 16:12 to make it clear that Siobhan Conmy said she isn’t planning to turn Street 66 into a reggae bar going forward, that would be somewhere else.]