What’s the best way to tell area residents about plans for a new asylum shelter nearby?

The government should tell communities directly about plans for new asylum shelters, some activists and politicians say.

It’s clear that posher parts of Dublin have more trees and greenery, but why? And will it ever change? Dublin City Council’s working on a new tree strategy, so now’s the time to make your voice heard.

Ballybough Road looked bare on Monday evening: swathes of concrete in the shadow of Croke Park, most of the few trees just struggling saplings, thumb-thick, and nearly leafless because of the season.

Two different passers-by used the term “concrete jungle” to describe it, when asked about the dearth of street trees provided by Dublin City Council in the northside neighbourhood.

Karl Dowling, who lives in the area, says this is one of the factors that keep the neighbourhood from being as nice as it could be. “It’s like the broken-glass theory: when people see a shitty place, they treat it like shit,” he says.

“You pay the same amount of tax as you do in Sandymount, and you don’t get as much,” he says.

Many of us have observed the difference between the hard concrete-and-brick of inner-city neighbourhoods, and the leafy gardens of the city’s posher districts. But a recent study based on data pulled together by UCD’s School of Geography with the four Dublin local authorities and the Office of Public Works quantified it.

It limited itself to street trees, not taking into account trees in parks or on private land. Still, of the approximately 100,000 trees in Dublin city, 60,000 are street trees.

The headline figures are worth repeating: according to the study, Dublin 4 had one street tree for every 7.7 residents. In Dublin 1, meanwhile, it was one tree for every 34 residents.

And the disparity is even starker if we get more specific.

In one area of Ballybough, the study counted 11 street trees for 3,482 people – that works out to one per 317 inhabitants – while the Sandymount area of D4 ran as low as one tree for every four inhabitants.

Generally speaking, in the area under consideration (between the canals, as well as Ballsbridge), there seemed to be a significant correlation between the socioeconomic status of an area and the amount of greenery there.

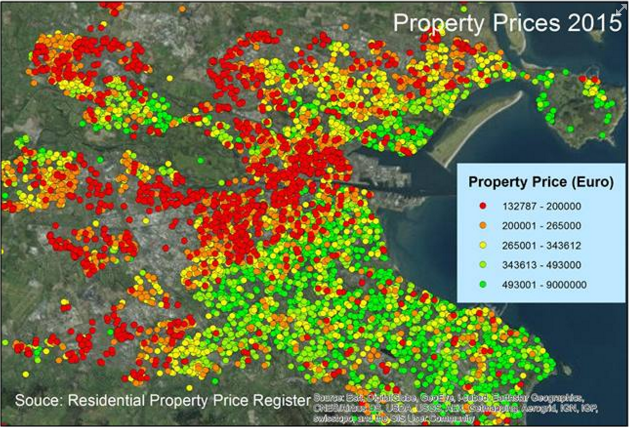

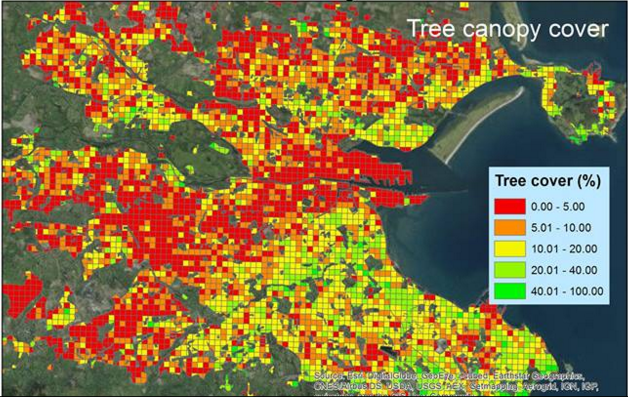

In these two UCD Geography Department maps, you can see it. One shows property prices, and the other, tree canopy cover, including not only street trees, but also trees on private land and in gardens.

“Looking at residential areas, the older suburbs in west Dublin, extending from Inchicore to Crumlin, feature low tree cover – here the built density is high and gardens are small,” said Gerald Mills a senior lecturer at UCD’s School of Geography. “In the south-east part of Dublin extending westwards to Terenure and Templeogue, the area per dwelling is larger due to bigger gardens, and there are wider roads with green margins.”

However, the differences appear still to exist when the focus is narrowed to just street trees, not including trees in gardens and parks.

Street trees are planted and maintained by the council, and counting them means we’re able to quantify the differences in public foliage across the city more easily than if we had to take trees in gardens and other private space into account.

Tine Ningal, senior technical officer at UCD’s School of Geography, has produced an inventory of all trees in the city. He agrees that “there is a direct relationship” between affluence and tree cover, that “in the more well-to-do areas, there seems to be a higher percentage of trees” compared with less well-off ones.

“I go running a lot and so I see other areas of the city,” says Dowling. “It’s just a different world.”

Based on the data, Paul Kearns and Motti Ruimy of Redrawing Dublin went one step further than calculating the ratio of trees to people. They used 2011 census data to calculate the “Needs Index” to assess the number of trees required in each area.

The 12 factors in the index include: the area’s population, the proportion of flats – because they don’t have gardens and so are more in need of street trees to make up for it – the levels of vehicular pollution, and the proportion of children under 12.

The Needs Index is then divided by the number of trees in the area to produce the Street Tree Deficiency Index.

According to these calculations, Ballybough East, which is spread over 37 hectares, suffers the worst deficiency of trees in the city. Sandymount, meanwhile, is best off.

Of course, most of the city falls between these two extremes: 25 of the 40 neighbourhoods included in the study were considered to have an “average high” or “average low” ratio of trees to inhabitants.

(If you want to check how your neighbourhood rates, you can do that here: scroll to the bottom and click the link to get a spreadsheet.)

Redrawing Dublin are currently working on an app to allow people visualise and calculate how many trees would need to be planted in a given area for there to be an appropriate amount, based on the current deficiency and the neighbourhood’s needs.

To give Ballybough the same proportion of trees as Ballsbridge, the city would have to plant 639 more trees.

Ningal argues that while Dublin is a reasonably green city in terms of the number of trees on its streets, its urban forest is still insufficient for its needs.

One of the main benefits of street trees is their ability to sequester carbon from the atmosphere. This is important in improving the air quality in busy urban thoroughfares, it benefits people’s health, and it helps reduce the city’s carbon footprint.

But many of Dublin’s busiest thoroughfares don’t have enough trees.

For example, Ningal’s work found Dorset Street to be the most polluted in the city, but it has only a single row of relatively small hornbeam trees between two lanes of traffic.

And that’s another problem: many streets only have a single variety of tree, leaving them all susceptible to dying if one gets a disease.

It seems to come down to history, wealth, and space.

“Wealthier suburbs were able to afford more street trees,” says Councillor Ciarán Cuffe of the Green Party. “And while I can understand the emergence of this issue historically, what I can’t understand is that this appears to be persisting into the twenty-first century.”

It’s a legacy that naturally takes a long time to overcome.

Marc Coyle, arborist and landscape architect with Dublin City Council, agrees that some areas “have a historical legacy of tree planting which accounts for the mature trees enjoyed in those areas today”.

It can take decades for some types of tree to reach maturity, leaving differences in terms of canopy cover even when tree planting has taken place.

There’s also the matter of space, “above and below ground”, which Coyle says is “perhaps the most critical” factor in deciding where trees can and can’t go.

In densely packed urban areas sometimes there’s just no room for trees. Footpath width, overhead cables, and underground pipes all pose problems for tree-planting.

Damage and vandalism to newly planted trees can also be a challenge. That’s something Ballybough resident Noah Fagan said he’s noticed. “They’ve tried to plant some trees,” he said. “They don’t get a chance. Kids break them.”

And sometimes residents actually don’t want trees. Councillor Mary Freehill of Labour said at a recent meeting that some people had objected to having hornbeam trees outside their houses, as they can block out the sun in the summer.

Councillor Gary Gannon of the Social Democrats, however, says the reason for the wealth-linked distribution of trees in the city “comes down to a mentality and a psychology of who we feel is deserving of these green spaces and these trees”. He says that inner city and urban areas are not given the same consideration as the “leafy suburbs we associate with Dublin” in terms of trees and green spaces.

Insofar as city council policy can help to reduce the inequalities relating to the urban environment, they have a number of plans and strategies to try and make things better.

A Draft Tree Strategy for 2016-20 was presented to the council’s arts, culture and recreation committee in March.

The strategy, presented by Coyle, outlines four key themes: protecting existing trees; caring for trees to promote healthy growth; planting more to ensure a sustainable urban canopy; and communicating effectively with the public and stakeholders. This strategy is currently open for public consultation.

Alongside this project, the City Parks division of the council is working with UCD to map and analyse the tree canopy in the city. Coyle says it will examine coverage based on land use, “key areas with a deficit of tree canopy and the potential environmental services delivered by trees, such as air quality and carbon storage”.

This will go beyond the quantification of trees, in an effort to work out more precisely where trees are needed and how they can help. It will also allow for a comparison with other cities, and inform the continuing effort to ensure an attractive urban environment for all.

The Draft Tree Strategy is out for consultation until 29 April. If you want to let the council know your thoughts, you can do it through this page.

CORRECTION: This article was updated at 12.54pm on Wednesday 20 April to reflect that the ongoing tree survey data is collected by UCD with the four Dublin local authorities and the Office of Public Works. The work of Redrawing Dublin is based in part on that data, but separate to the project.