What’s the best way to tell area residents about plans for a new asylum shelter nearby?

The government should tell communities directly about plans for new asylum shelters, some activists and politicians say.

To some, the Santry River Greenway may seem like an unattractive cycle route. But a reconnaissance mission shows that it has great potential.

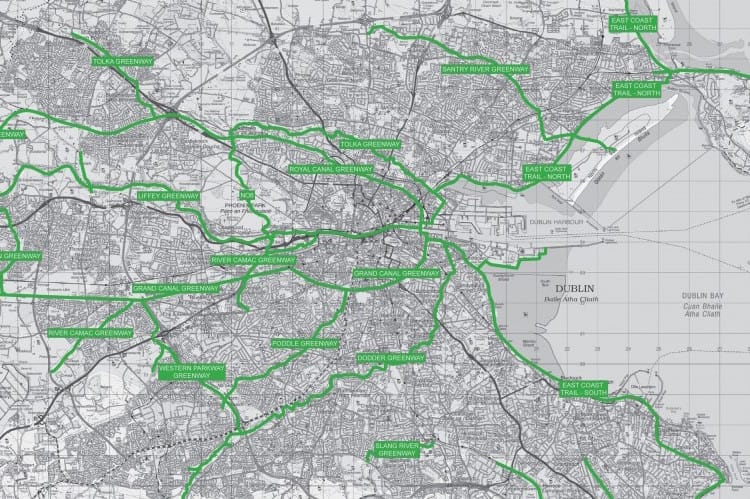

Of all the National Transport Authority’s proposed Strategic Greenways in Greater Dublin, the Santry River Greenway sticks out.

Most other routes lead into the city centre, but the Santry River Greenway is an orbital route, running through Dublin’s northern suburbs. The route only connects to one other greenway and runs through some of the most auto-dependent parts of Dublin.

“This could look, to some people, as the most unattractive route,” says Odran Reid, strategy development manager at the Northside Partnership. “Yet I think it would probably be the one with the most positive local benefit you could get.”

The Northside Partnership is a local development company, set up in 1991 to address the long-term unemployment and social exclusion in Dublin’s Northside neighbourhoods. And they’re big supporters of the Santry River Greenway (labelled on the map below). As they see it, it could break down barriers between communities, connect people to jobs and encourage more active transport and healthy recreation.

The greenway has its origins just below Dublin Airport and follows the Santry River, which is more akin to a stream. It passes through some of Dublin’s most deprived neighborhoods, like Ballymun and Darndale. Then it winds its way through the more affluent Raheny before finding the ocean just beside the causeway to Bull Island. Its route links these disparate communities, which are fragmented by industrial estates and major roads.

Over the years, the Northside Partnership has teamed up with Dublin Institute of Technology’s (DIT’s) planning students and lecturers on several projects. One of the most recent? The greenway.

Last Friday, I joined DIT Transport and Mobility Lecturer David O’Connor and Northside Partnership Local Development and Education Programme Manger Dr Matthias Borscheid to perform what O’Conner described as a “reconnaissance mission”.

The route of the greenway has already been decided by the NTA and outlined in the Greater Dublin Area Cycle Network Plan. But O’Connor and Borscheid wanted to see what opportunities exist to enhance the neighbourhoods the greenway will pass through. This way, when the design stage comes, the Northside Partnership will know what to ask for.

We met at the Topaz Petrol Station on Ballymun Cross, just South of the M50, to plan our journey. The NTA’s proposed greenway network map indicates that the Santry River Greenway will begin just to the east of the Ballymun Road.

Outside the Topaz, cars flew by, still carrying their speed from the M50. “This area doesn’t have a proper centre,” said Borscheid. “This kind of corridor would help the area grow together and allow people to venture into other parts of the Northside.”

We set off to see for ourselves how navigable the route currently is.

The NTA’s Greater Dublin Cycle Network Plan goes into great detail about their plans to develop the Liffey, Grand Canal and Royal Canal greenways, but only gives two lines to describe the Santry River Greenway. They say that the proposed greenway follows “a network of public parks and established tracks along the river”.

Although a green corridor does currently exist along much of the Santry River “it is interrupted by factories and big roads”, explains Borscheid,

Many of the parks along the route suffer from excessive fencing. Reid points to the Stardust Memorial Park as an example: “Realistically, if you want this to work, it has to be an open park.”

The fear of antisocial behaviour led the council to not only fence the perimeter of the park, but the memorial for which the park is named, which is only opened once a year, on the anniversary of the Stardust Nightclub fire.

Despite the fencing, many of the parks are good facilities. The Santry Demesne, only a stone’s throw from the Ballymun Road, was opened ten years ago by Fingal County Council. It was once a palatial house and gardens; now the grounds have been retrofitted into a 72-acre park, adjoined a 15-acre linear park along the banks of the Santry, fitted with exercise equipment.

At the end of the Santry Demesne, the river is culverted beneath the Swords Road and those wishing to follow it cross the traffic above. A nondescript entrance on the east side of the road leads to a track that follows the river.

The proposed greenway is bordered to the north by industrial estates on either side of the M50, many of which are vacant. To the south are housing estates separated from the Santry River by fencing.

The neglected track is lined with an ugly metal fence, which spoils the wooded riverbank to the south.

Things get interesting when the path dives below the M50. The underpass floor is strewn with broken glass and the walls are emblazoned with graffiti. Walking through it is a bit foreboding.

The crackle of glass beneath our feet is the only sound as we walk, in silence, feeling like this is a piece of the man-made environment that has been forgotten.

We wonder how this route could be made safe for users. Borscheid explains that to attract users, the route has to not only be made safe, but also be made to feel safe. “A physical revitalization and CCTV could go a long way,” says O’Connor.

The path enters Coolock Lane Park, which leads into the heavily fenced Stardust Memorial Park. On the far side of the park, the Santry River enters the old Chivers Jam Factory site, which is up for sale.

The gates surrounding the empty industrial site extend all the way to Greencastle Road, enclosing the green space between the street and the river that would need to be used for the greenway.

Once we cross the Malahide Road, the neighbourhoods surrounding the Santry Greenway route change. The green spaces are less likely to be strewn with litter and the hedges around houses are better landscaped.

Sitting in a pub in Raheny near the end of the route, we reflect on the journey. “It was kind of surreal,” said O’Connor. “We went around a corner and suddenly were in a completely different part of the city.”

The Santry River Greenway could be a tough sell for many of the communities that surround it.

Many segments of the route are isolated. A physical redevelopment, better lighting and CCTV may not be enough to convince people that the route is safe.

Reid suggests that some sort of permanent security service for the greenway might be the answer. Not only would such a service assuage the fear of anti-social behaviour, it would also provide local employment opportunities.

“A lot of permeability and walkability projects are opposed, in my view, for the wrong reasons,” says O’Connor. “But the evidence suggests that if things are done right and areas are developed in the right ways, better facilities, greater connection and improved permeability will be better for everyone.”

The Northside Partnership, in O’Connor’s eyes, will be crucial in reaching out to the affected communities and “building that confidence and making sure that it’s a really positive piece of social infrastructure for everyone”.

“You have to be honest with communities and you have to build trust with communities,” he said. “And that takes work, and it takes time.”