What’s the best way to tell area residents about plans for a new asylum shelter nearby?

The government should tell communities directly about plans for new asylum shelters, some activists and politicians say.

Dublin City Council is in the midst of writing its new development plan, for 2022–2028, which will include what kind of building should be allowed where.

On a recent sunny Monday, standing on the Sandymount promenade, Doc O’Connor recalls the day, many years back, when the Dodder River broke its banks and flooded his street, Stella Gardens, in Irishtown.

“I was looking out the window at about half three in the afternoon and I just saw this almighty amount of water coming down the road,” says O’Connor, a tall man wearing a grey hoodie. “It was just amazing.”

His floors got soaked. Some of his neighbours suffered much worse. “The cottages were destroyed,” he says. “It came up over their windows.”

Since then though, Dublin City Council has raised the height of the Dodder flood wall and so, he says, he feels confident it won’t happen again.

But as the climate changes, Dublin is likely to be at increasing risk of flooding from greater rainfall, rivers more prone to burst their banks, and rising sea levels, says Conor Murphy, a Maynooth University professor, who sits on the Climate Change Advisory Council’s Adaptation Committee.

Like in Irishtown, in Sandymount too, the council plans to build higher walls to hold back the tide – and until that is done new developments aren’t allowed in high-risk parts of the neighbourhood, according to the Dublin City Development Plan 2016–2022.

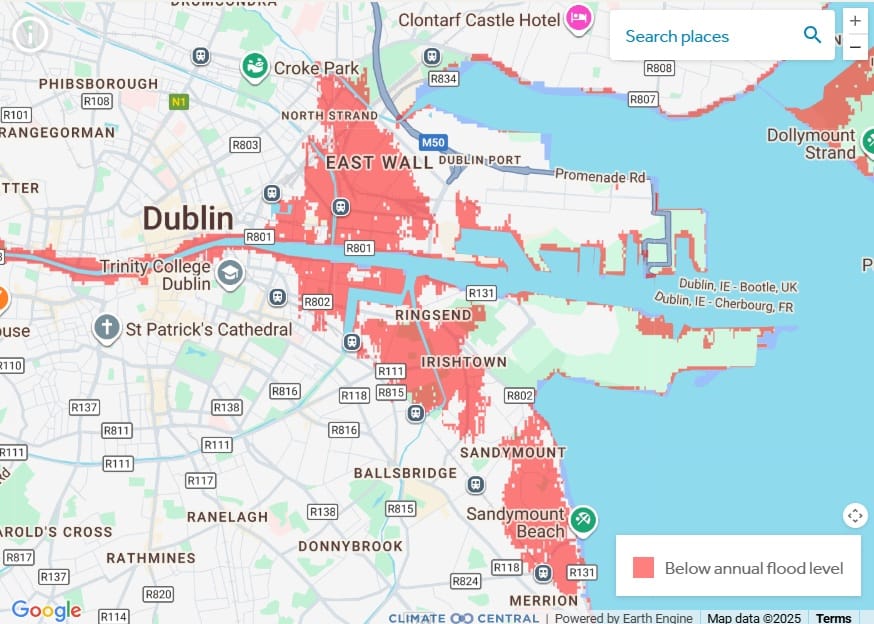

Maps predicting future flooding show that by 2050 large swathes of coastal Dublin city could be below annual flood level, including parts of Sandymount, Ringsend, Irishtown, the Docklands, East Wall, Clontarf.

Murphy says that, regardless of what walls the authorities erect, it is still risky to build new developments in coastal areas that are at high risk of flooding.

Walls can hold back the sea but they can also create a “false sense of security”, he says.

“Where you have flood walls and hard infrastructure they are built to a design standard and if that standard is surpassed it can create really catastrophic floods.”

Dublin is at risk from flooding from the rivers and heavy rainfall as well as from the sea, Murphy says. All three could be worsened by climate change, he says.

The location of the city means water runs downwards from the mountains, he says.

“We have seen quite catastrophic floods, particularly in places like Bray,” he says, “around the Dodder Valley and even around Drumcondra with the Tolka”.

The drainage system is old, too, and that exposes Dublin to flooding when it rains heavily, he says.

Then there is the increasing risk of sea flooding. “Typically the risk from coastal flooding comes from having high tide combined with a storm surge,” says Murphy.

A storm surge is when low pressure elevates sea levels and the wind from a storm pushes the sea inland. That is what happened in Ringsend in 2002, he says.

The sea level is definitely going to rise, Murphy says, it’s just not clear yet by how much.

It takes time for the rise in sea levels to catch up with the increase in global temperatures, so even if global warming was contained, the sea level would still rise.

It is difficult to predict exactly what will happen to coastal areas of the city, says Murphy.

If greenhouse gas emissions continue at their current levels, globally, the sea level would be expected to rise between 0.6 metres to 1 metre in the medium term, he says.

“If we get our act together” and significantly decrease our greenhouse gas emissions, the rise in sea level could be around 0.3 metres to 0.6 metres.

Storms could become more intense too, he says, and if they do that will cause additional problems.

Dealing with the rising sea level will be expensive for all coastal cities. There is the cost of building defences, and they are also expensive to maintain, he says.

There is the human cost too, as coastal communities are changed completely by the walls. “Place matters, it’s part of community,” he says.

The impact on health and well-being should be taken into account in the planning process, so authorities should look at building barriers that can be raised and lowered so that recreational spaces like promenades aren’t lost permanently, he says.

The Dublin City Development Plan 2016–2022 says that sensitivity to climate change in Sandymount is “extreme” and that parts of Sandymount are not suitable for development at the moment until further flood defences have been completed.

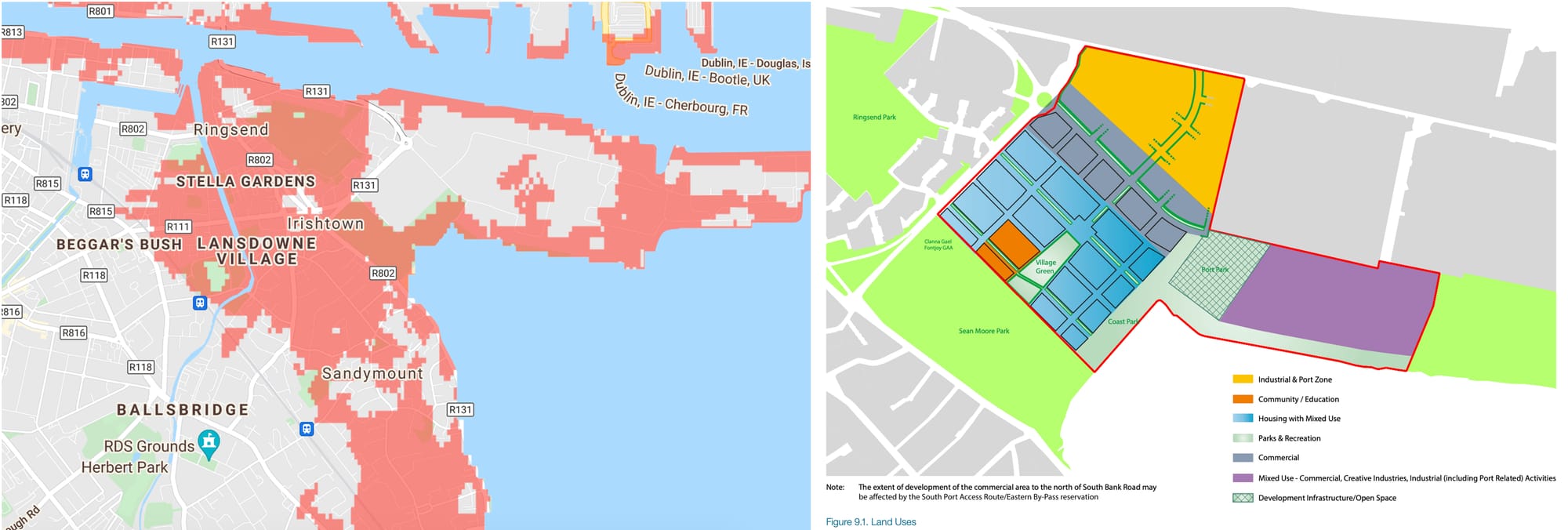

There are around 3,500 homes planned for the nearby Irish Glass Bottle site, which is shown in the map by US-based nonprofit Climate Central on an island of land surrounded by areas that in 2050 would sit below the annual flood level.

The Ronan Real Estate Group, which is involved in developing the Glass Bottle site, declined to comment on how it plans to mitigate flood risks for the project. Dublin City Council has not yet responded to queries about this sent on 7 October.

According to the development plan, developing the area to the south of Dublin Port and the Tom Clarke Bridge, which includes part of the Docklands and Irishtown, is considered essential.

“This area is essential for the future expansion and operation of Dublin Port and its related operations,” it says.

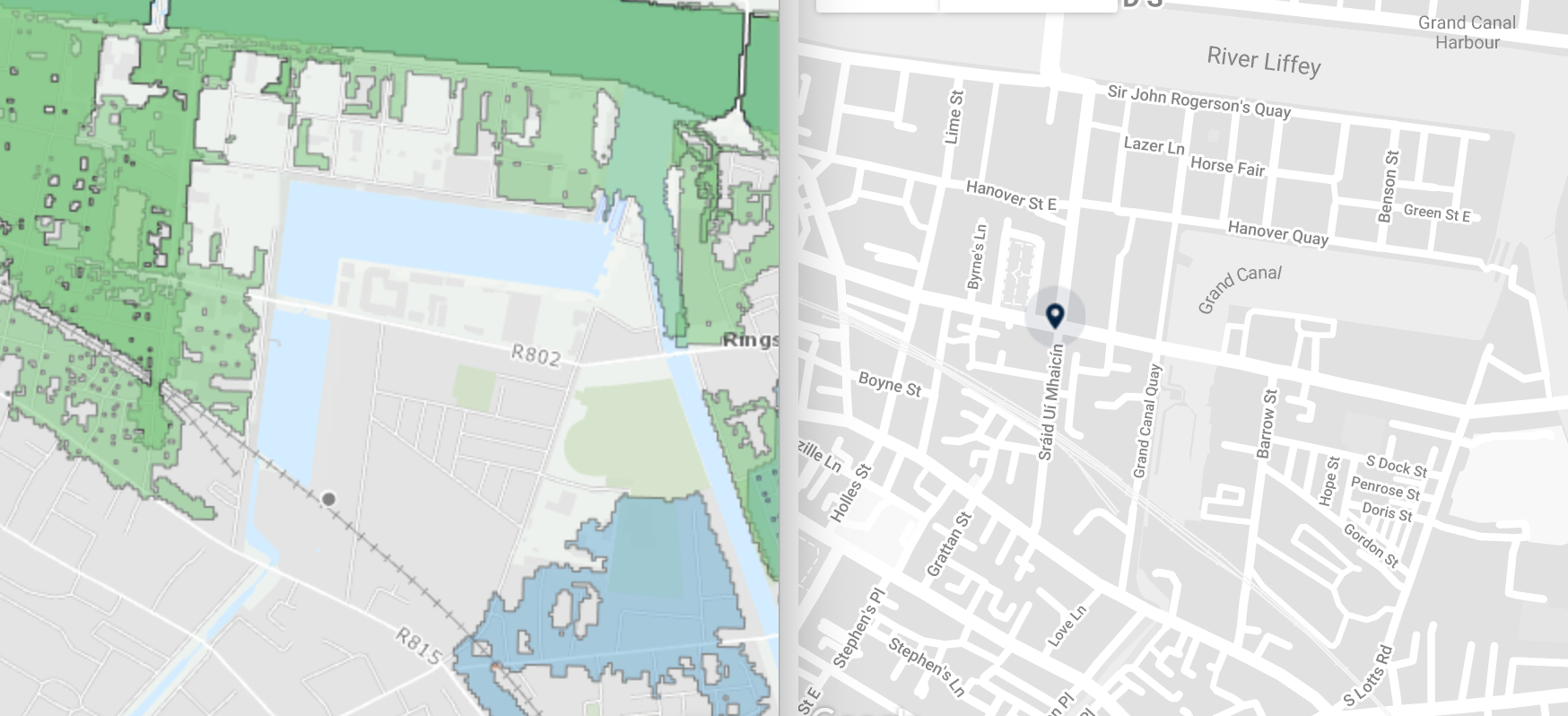

Slightly westward, Dublin City Council has approved a plan by Bartra Development for a 10-storey building the developer is calling The Sidings, with 160,000 square feet of office space, adjacent to the Grand Canal Dock DART station.

The OPW’s maps using their “mid-range future scenario” of an increase in rainfall of 20 percent and a sea-level rise of 0.5 metres, shows that project at risk. Bartra has not yet responded to query about whether it took such predictions into account, why then they would choose to build there, or how they planned to mitigate the flood risk.

A spokesperson for the Office of Public Works (OPW), the lead agency on flood-risk management in Ireland, says that it provides flood maps to local authorities, to assist planners to make decisions on individual applications.

In an area that is not yet built upon, called a greenfield site, it is more likely that planning will be denied if there is a risk of flooding, says the spokesperson.

But on land that was previously used for industrial purposes, the rules are different. “In brownfield development, risk reduction, e.g. by raising floor levels as well as appropriate flood defences may be taken into account,” he says.

Green Party Councillor Michael Pidgeon, who chairs the council’s environment committee, says that the whole of the city centre could be at risk from rising sea levels. “So much of it is difficult to predict,” he says.

If the sea level rises significantly, one-off housing developments will be very vulnerable, but the government will have to invest in flood defences, to protect the central parts of cities, he says.

“You are going to have to put in mitigation measures there, whether that is walls or trenches,” he says.

Dublin City Council is now in the process of writing its next city development plan, for 2022–2028, which will include decisions on assessing flood risks in areas across the city, and what kind of building should be allowed where.

In a submission to a public consultation on the new development plan, the OPW said that planning authorities – like Dublin City Council – need to consider climate change impacts in preparation of their development plans.

“[S]uch as by avoiding development in areas potentially prone to flooding in the future, providing space for future flood defences, specifying minimum floor levels and setting specific development management objectives,” it says.

The only real solution is to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, says Murphy, the professor at Maynooth University, but another thing that authorities can control is the planning process.

In New Orleans the city relied on its flood walls and so when their capacity was breached during Hurricane Katrina, the results were terrible, he says.

He is not suggesting that would happen in Dublin, but he says the existence of the defences can create a “false sense of security and that development is safe”.

Sometimes that means that development is allowed in areas where it shouldn’t be, he says.

“Engineering is based on the assumption that the past is the same as the future and if you are talking about climate that is not necessarily the case,” says Murphy.

The planning process can be used to mitigate risks. “If we are going to continue with business as usual we are going to increase risk in the future,” he says.

Back on the promenade in Sandymount, Sandra Morrissey says that she often sees seawater splashing over the wall in wintertime. The houses facing the sea have sandbags and frames protecting their doors, she says.

“Yes of course we should have barriers,” she says, but she hopes they will be ones that can be raised and lowered.

She has never thought about the possibility of the barriers being breached. “That sounds scary,” she says. “Could that happen for real?”

– with additional reporting by Sam Tranum

Get our latest headlines in one of them, and recommendations for things to do in Dublin in the other.