What’s the best way to tell area residents about plans for a new asylum shelter nearby?

The government should tell communities directly about plans for new asylum shelters, some activists and politicians say.

Across Dublin, rough sleepers have given up on calling the “homeless freephone” to get a spot in a hostel for the night. There’s no point, they say.

Ritchie Sweny gave up on the homeless freephone several months ago.

He was sat outside the Spar on Nassau Street on a recent Monday evening, with his back to the wall and a paper cup clasped between his knees. A metal fence ran along the roadside, shielding the dug-up tarmac and Luas works.

His list of complaints is familiar: there were never beds, he found one guy on the end of the phone was rude, he couldn’t take a bed unless his girlfriend had one too, the hostels were no place for a now-clean former heroin user.

“I don’t bother anymore,” he said.

Later that evening, he picked himself up from the pavement and walked with his girlfriend, who carried a hamster cage in her left hand, across the city, back towards a squat where they now sleep, under a corrugated roof that leaks when it rains.

Sweny is far from a lone voice.

“The freephone has been a bone of contention, particularly with people who would be on the streets,” says Anthony Flynn, the head of Inner City Helping Homeless.

At the moment, those who are homeless and don’t have a guaranteed bed in a hostel have to call the freephone each night, or several times each night, if they want one.

The freephone operators at Central Placement Services on Parkgate Street take a look in the

system and allocate a bed, and set a time that a person has to be at the hostel by. If somebody doesn’t arrive there by a certain time, then the bed is put back into the system, and doled out again, says Flynn.

But for many, it’s a night-by-night system that is full of uncertainty. “When you’re number 46 on a system, and you come down to number 1 and you’re told there are no beds available … ,” he says. “The system is designed so that people are actually suffering.”

Outside the General Post Office on O’Connell Street on a recent Thursday evening, where the Hope in the Darkness team were ladelling hot chicken curry into cardboard bowls and handing out hot dogs, many said the same.

You find yourself calling several times a day, said a guy who gave his name as Bernard Crow. “You can be 50 in the waiting queue.” You call at 4.30pm. 10.30pm. Later, again. Then, it’s a sleeping bag.

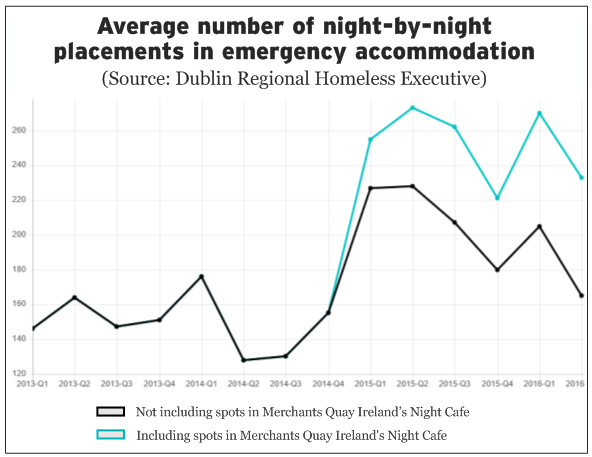

The number of people who get night-by-night beds in emergency accommodation seems to have fluctuated over the last few years, and it’s hard to know exactly what the figures mean.

In the last three months of 2013, an average of 151 people were given a night-by-night emergency bed in the Dublin City Council area. The figure was similar in the last three months of 2014, when 155 people were given night-by-night beds on average. Then the numbers jumped.

In the first three months of 2015, an average of 227 people were given night-by-night beds — but that figure seems to have dropped a bit since. Down to 205 in the first quarter of 2016, and further down to 165 in the second quarter of 2016.

It depends a bit how you count, though. If you add in the places at the Night Cafe run by Merchant’s Quay Ireland, then there were 270 people each night on average in the first quarter of 2016, and 233 on average in the second quarter of 2016.

Flynn of Inner City Helping Homeless said he has been trying to work out for a while exactly how many beds are in the system, and whether there has been a decrease. Unable to get a clear answer, he has filed a Freedom of Information Act request.

One of the possible reasons why it looks as if there has been decrease in night-by-night beds on offer, down to 165 in the second quarter of 2016, might be that more people are being given a bed for a longer block of time.

As the quarterly reports from Dublin Regional Homeless Executive note, in the third quarter of 2015, 20 beds were given over from one-night-only bookings to rolling bookings. That meant fewer beds for the nightly freephone, but also fewer people having to call in.

The report for the fourth quarter of 2015 says the same: “Despite the increase in the number of beds in the Quarter 4 2015 (…), the number of placements being made began to fall as work on reducing ‘nightly only’ placements progressed.”

“They’re trying to maximise the amount of seven-night beds that they can give out,” says Mark Kennedy, head of day services at Merchant’s Quay Ireland. “It’s stressful for people who are having to call into the freephone every night.”

Where homeless services can, they’ve been giving out the rolling beds, said Kennedy. “Whether it be a week, or longer than a week.” It’s one step towards finding a way out of the chaos of homelessness.

Even as that happens, though, the average number of homeless individuals — either through the placement service or the homeless freephone — who homeless services are unable to accommodate saw a bit of a spike in the most recent statistics.

That figure was 17 a night in the first quarter of 2015, and then it rose to 29 in the third quarter of 2015, to 16 in the first quarter of 2016, and up again to 29 in the second quarter of 2016.

Some complain that the freephone operators aren’t doing their job properly, or are rude. On Nassau Street, Sweny said that he never wanted to take a bed when his girlfriend hadn’t been allocated one, because he didn’t want to leave her sleeping rough alone.

Sometimes, they’d call at the same time, and he would have to turn his down, when it transpired that she wouldn’t have one.

As he tells it, one operator would tell him that a mark would be left next to his name, to say that he’d turned down a bed. “It happened a few times that I was left out here, or she was left out here,” he said.

But as Flynn of Inner City Helping Homeless sees it, the operators are doing their best with the resources that are there. “When people are continuously ringing, they have to deny them access to a bed because there is nothing there in front of them,” he said.

Back in December 2014, one of the points on then-minister Alan Kelly’s 20-point plan to deal with homelessness was a review of the operation of the homeless freephone service “as a matter of urgency”.

When Flynn asked about that, he was told that the problem wasn’t the freephone as such. “What we had been told was that it wasn’t an upgrade of system or additional staff that were required, we were told that it was extra beds,” he said.

The council is conscious that it needs more. Once again, it’s a supply issue. That’s what then-Homeless Services Chief Cathal Morgan told councillors at the housing committee at the close of July. There are four projects that they are looking to bring forward, he said. “There is a capacity issue. We do need, we feel, an additional 100 beds.”

That’s the conclusion of Kennedy of Merchant’s Quay Ireland, too. It’s a well-organised system so there are zero beds left at the end of the night that are wasted because of people not turning up, said Kennedy. “We all know that there just isn’t enough beds to go around,” he said.

The four Dublin local authorities are facing significant additional demand for emergency

accommodation, but it isn’t easy to bring more beds on line, said Sorcha Donohoe, a spokesperson for Dublin Regional Homeless Executive.

“This remains a challenge as securing the use of suitable facilities for emergency accommodation can be delayed and diverted due to opposition best characterised as nimbyism,” she said.

In the same meeting in which Morgan told councillors that homeless services needed more beds, he also pointed to the differences in the short-term and long-term approaches to dealing with rough sleeping and homelessness.

Said Morgan: “I would make one comment in relation to this. One of the success factors of the [Action Plan For Housing and Homelessness] has to be a massive descaling of emergency accommodation.”

For a while now, there’s been an ongoing attempt to move away from large-scale dormitories and a stepping-stone model, towards more immediate supported private accommodation. Something closer to the model known as “housing first”.

“The council needs to build in the principal that the supply will mean that they’re moving away from large-scale dormitories and institutions, that ultimately are not great for people, and rely on a housing first model where professional staff are supporting people, effectively in their homes, rather than in hostels,” said Morgan.

As Flynn sees it, the priority is getting people somewhere to stay, and he would like to see more efforts to give even more people rolling beds, rather than the night-by-night beds that offer less stability, he said. Whether it’s dorm-style or single units, it just has to be something, he says.

“We need to concentrate on getting them off the streets and into these dorm-style dwellings until we manage to get them housing, or back into normal living,” said Flynn.

On a recent warm Thursday evening, William McDerby was sat at the base of one of the grand pillars of the General Post Office, looking out over the broad boulevard of O’Connell Street. He has a tangle of silver curly hair, black-rimmed glasses and clean blue jeans.

For about a year-and-a-half, McDerby said he would call the freephone, and, unlike others who might turn down beds in places they wanted to avoid, he’d take what he was given. “You could be anywhere, though,” he said.

Now he has a longer-term spot in a hostel where he can come and go as he pleases, the staff treat him well, he says. “Now, thankfully, I’ve got a permanent residence.”

Get our latest headlines in one of them, and recommendations for things to do in Dublin in the other.