Skeletal remains found during construction at Victorian Fruit and Vegetable Market

The bones are thought to come from the major medieval monastery at St Mary’s Abbey, and further excavation works are ongoing.

“I think it's so sad that a beautiful little house was destroyed,” says Rosita Sweetman. “It seems we are incredibly bad at managing our housing stock.”

Rosita Sweetman was saddened to learn that her mum’s old home, a 19th-century villa on Park Avenue in Sandymount, had sunk into dereliction, she says.

Once home to the author Arthur Power – who wrote the memoir Conversations with James Joyce – the pretty redbrick house was in good condition when her mum passed away in 2002, says Sweetman.

The family sold the home the same year, she says. Years later, a friend told her it was boarded up.

At first, Sweetman felt emotional about going back to take a look, she says, and she was devastated when she saw it. “The roof had been ripped off, with only the facade remaining.”

Last month, Sweetman was stunned to learn the house was completely gone, she says.

Now under new ownership, construction on its replacement has started and the home is set to be rebuilt and extended, according to the planning permission.

But that it fell into such a state that it was lost is an indictment on the current planning enforcement system, says conservation architect and long-time anti-dereliction campaigner Róisín Murphy.

“I think it's so sad that a beautiful little house was destroyed,” says Sweetman. “It seems we are incredibly bad at managing our housing stock.”

Geodirectory figures put 1.1 percent of Dublin’s housing as derelict at the end of last year.

“There has to be accountability,” says Murphy, about dereliction in general.

The government must reform and strengthen the compulsory purchase process, and councils must hire more staff in planning enforcement and conservation, she says.

She isn’t surprised, she says, that Dublin City Council struggles to prevent dereliction in conservation areas.

It sometimes can’t even force owners to maintain buildings that are on the record of protected structures, says Murphy.

And whenever any building is demolished, there is also an environmental cost from the waste, she says. “You owe the carbon back to us.”

Number 40 Park Avenue in Sandymount is not on the record of protected structures, but the street is in what is zoned as a “residential conservation area”.

Sweetman has photos from the brochure from when her family sold the house in 2002. The outside shots show a clean red-brick house, with steps up to a blue door. Inside, the dining room has dark wood furniture, wooden floors and long red curtains.

Tracking the decline of 40 Park Avenue on Google Street View shows the house was intact with a car parked outside it in 2014 but by 2017, the roof was gone.

Neighbours contacted the council repeatedly to complain that the house was falling into dereliction, says Sweetman.

A council spokesperson says that the roof was removed around 2016. At some point before 2020, the house was entered on the derelict sites register.

In December 2020, Pat Halpin applied to the council for permission to build two two-bedroom apartments, around 84sqm each, and a new four-bedroom house of around 128sqm.

An architect wrote a letter to council planners as part of the application saying that Halpin had been ill, which had contributed to the house’s decline.

The proposal was to retain the facade, demolish the “existing return” and lower the ground floor to create a terrace at the front, and put the two apartments in that building, says the planner’s report.

At the back, Halpin proposed building a new four-bedroom house, across one and two storeys, with access via a side passage.

There were 12 observations, some of which raised concerns about the development, including the loss of period features, including the chimneys, impact on the privacy of neighbours, flood risks – it is on a flood plain – and some said the plans constituted overdevelopment.

Council planners knocked back the proposal citing impact on privacy of neighbours and the flood risk, and heritage concerns.

Efforts to reach Pat Halpin through an email address for his partner from company records, through an accountant and a lawyer who previously represented him, and on an old mobile phone number, weren’t successful.

In 2024, 40 Park Avenue sold for €757,000 according to the property price register.

At that stage, it had been on the derelict sites register for years.

According to the council spokesperson, “the rest of the property had been demolished circa 2016 and all that appeared to remain was the front façade and a portion of the side gable wall”.

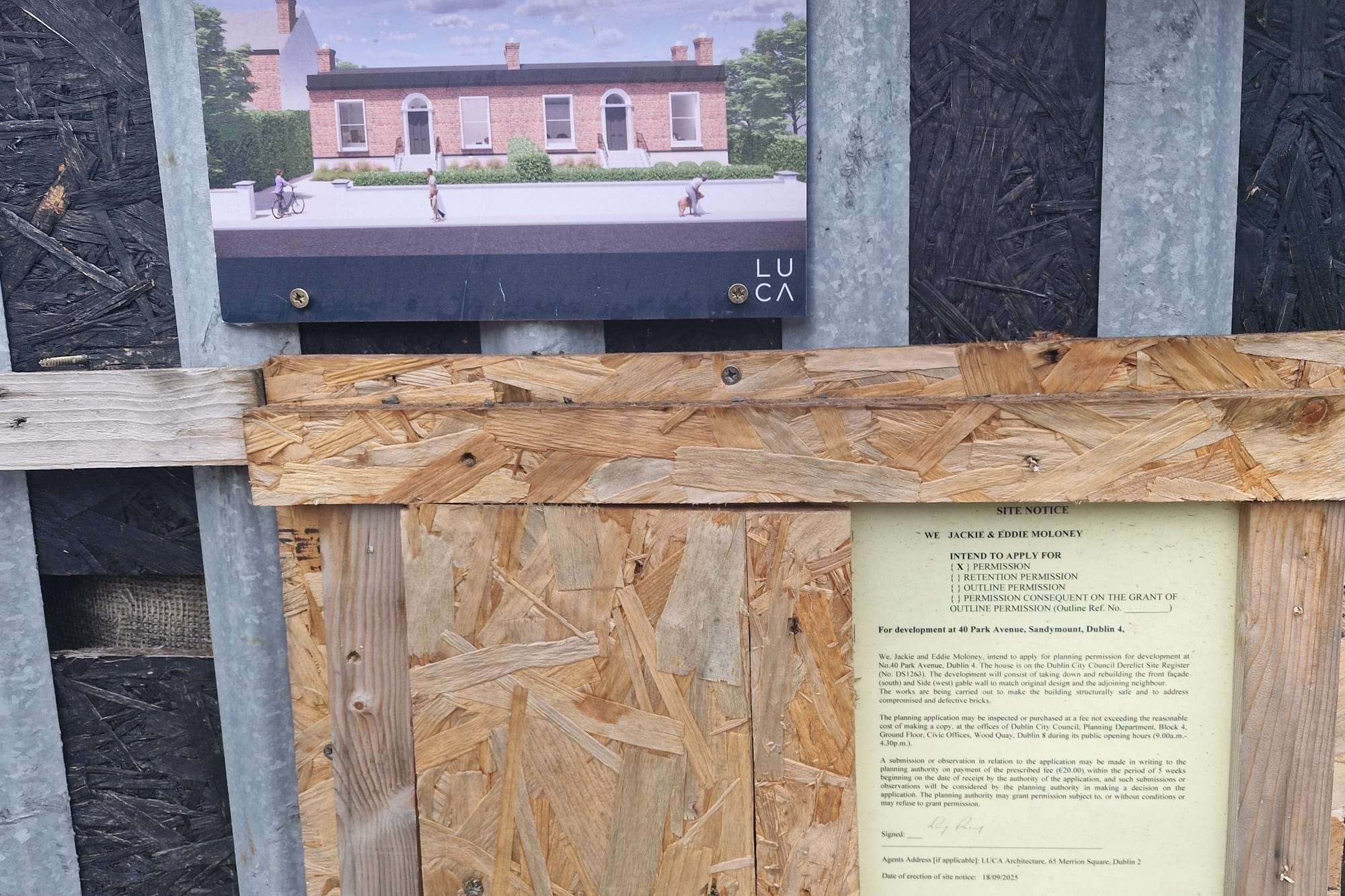

In August 2025, Jackie and Eddie Moloney got permission to restore the house and build a two-storey extension with a flat roof and rooflights at the back.

They would restore the front façade and reinstate the front chimney and original floor levels, install new timber sash windows and fully refurbish the house, says the planner’s report.

But the next month, they had to apply for planning permission again. They couldn’t restore the facade and needed to demolish it instead, the application says.

“The development will consist of taking down and rebuilding the front façade (south) and Side (west) gable wall to match original design and the adjoining neighbour. The works are being carried out to make the building structurally safe and to address compromised and defective bricks,” says the planner's report.

The planning permission, and demolition, was granted.

On 30 January, a long empty site with a wheelbarrow, mixer and building materials was visible through gaps in the hoarding in front of what once was Sweetman’s mum’s home at 4o Park Avenue.

Sweetman says that the government should do more to make sure homes are maintained so they can continue to be lived in, given the housing crisis.

It should protect historic buildings, she says. “They are not an infinite resource.”

Says Murphy, the conservation architect: “There has to be some sort of use it or lose it.”

Many European countries have robust powers of enforcement to prevent dereliction, particularly of historic buildings, she says.

She worked in the United Kingdom, where every five years, owners of protected structures have to prepare a survey to demonstrate that they are maintaining the property, she says.

That measure should be introduced here, she says. “You have an obligation to your neighbours.”

She isn’t surprised that the council didn’t succeed in getting the owners to maintain the house at 40 Park Avenue, she says, as the council struggles to enforce rules even when a building is on the record of protected structures because they don’t have enough staff in planning enforcement and conservation.

“We need stricter rules and more enforcement,” she says.

The government should overhaul the compulsory purchase process to make it much stricter, says Murphy.

“Even large developers that own protected structures are allowed to sit on long-term dereliction right in the city centre,” says Murphy, pointing to Moore Street and Aldborough House.

That is something city councillors have been calling for also. Although, even when Dublin City Council does purchase a property by force, that can sit and crumble for years be it because of other priorities, changing staff, or a reluctance to spend to do it up.