What’s the best way to tell area residents about plans for a new asylum shelter nearby?

The government should tell communities directly about plans for new asylum shelters, some activists and politicians say.

“I don’t know, it’s to feel like you’re in a fantasy world of what Dublin used to be,” says Eddie Kenrick, on why he makes it.

Eddie Kenrick pulls a 1986 issue of Magill from the pile. Spread across his bed are copies of other magazines, booklets, newspapers.

“I’ve had this, all this kind of bullshit, forever,” he says. He picks out a small yellow booklet, a fanzine called Loserdom, a favourite of his growing up.

Flicking through the pages of these old booklets and magazines, Kenrick often finds something that catches his eye, he says – maybe a design feature he likes, or an image or font that fills him with a feeling of nostalgia for his childhood.

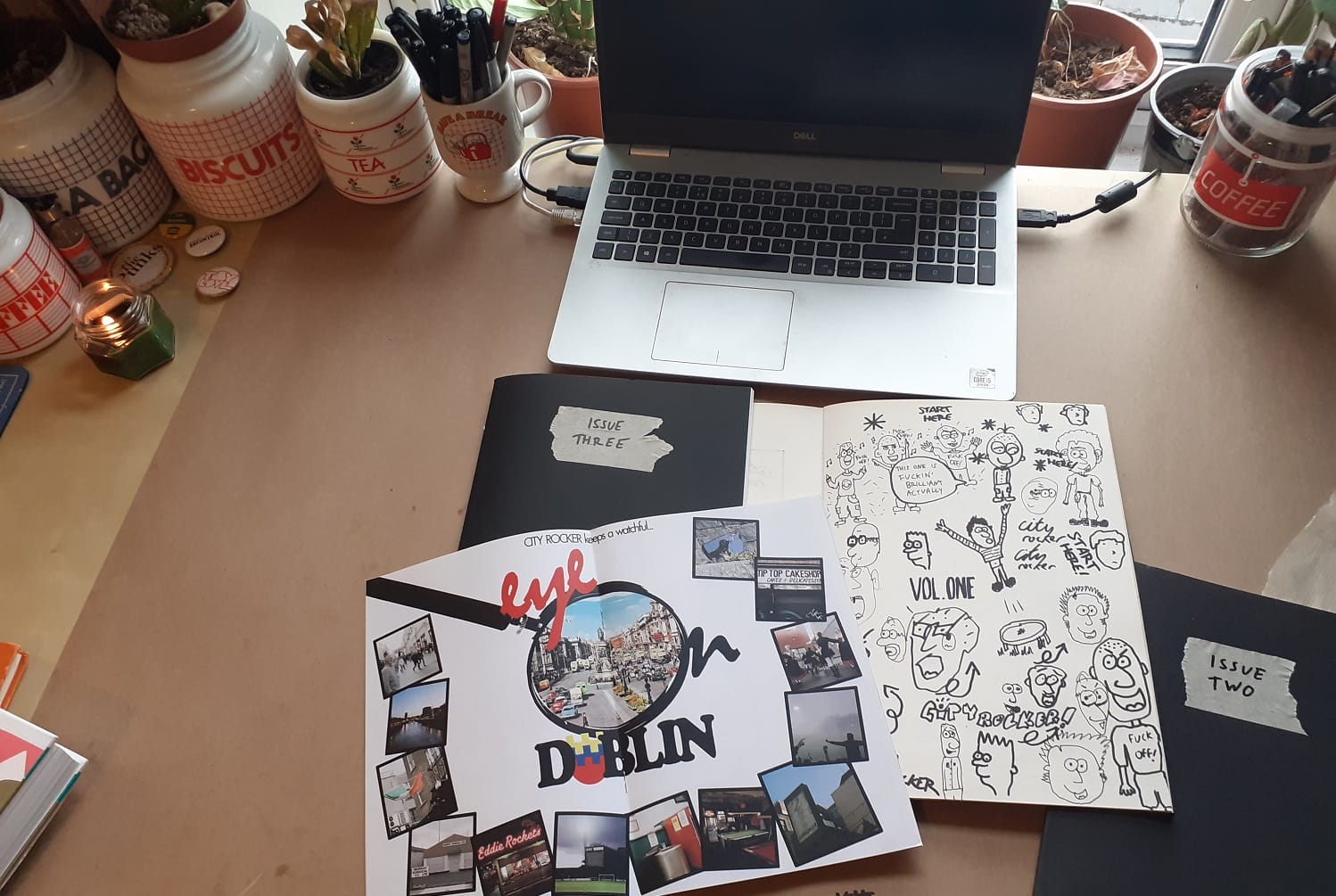

Hoping others may get the same warm vibes, Kenrick has since the summer been scanning clippings gathered for curiosity’s sake over a decade, and assembling them into a quarterly zine, called City Rocker.

The zine on its second issue. “Going back, as far as I can remember, I have always just been drawn to, I think it’s stuff that reminds me of what Dublin was like when I was a kid,” he says.

City Rocker is something that Kenrick himself would want to buy, he says, made mostly for himself. “Rather than filling a void, or thinking that anyone else might like it. I guess if they do, that’s a bonus.”

Within the pages of City Rocker are collages of ad snippets, pen and paper games, and memorable imagery that Kenrick came across while rifling through the collection of old magazines, yearbooks, journals and newspapers stacked around his room.

“This is a photo I took at a scarecrow festival,” says Kenrick, running his finger to point out images. “This is from an old NME, like. This is from a newspaper from the 90s. So’s that.”

On some pages are old recipes, biking routes, or certified ads. But other pages show images that Kenrick says he just liked, or his own doodles. “It’s a very weird mishmash of things.”

One page shows a word search that neither Kenrick nor his readers have been able to solve. Another has a join-the-dots pint of Guinness from an advert in a secondary-school yearbook. “Truly, truly bizarre,” he says.

Making the zine – rummaging through clippings and laying them out – brings him nostalgic feelings from his childhood and coming up to visit Dublin from Portlaoise, he says.

He can remember in the late 90s, dragging his mum around music shops on Grafton Street, Wicklow Street, and the quays, or street vendors on O’Connell Bridge, to buy bootleg tapes.

From between his shelves of vinyl sleeves, Kenrick pulls out a cassette tape and places it in the slot of a silver tape player, with a plastic clatter that sounds retro.

An electric guitar plucks over a cheering crowd. “It’s from when Metallica played in Dún Laoghaire [in 1988] and someone went to the gig with like a fucking tape recorder.”

Kenrick and his brother would buy bunches of bootleg tapes for £1 each, he says, and it was life-changing. “We’d come back and listen to a really crap-sounding bootleg like a hundred times, and just like, dream about going back up and getting another crap tape.”

Searching in charity shops to gather magazines and ephemera feels a bit like how he’d feel as a kid from a small town racing around the big city for new tapes, he says.

City Rocker is a way of expressing that feeling, he says. “It’s like literally just recreating the childhood experience of walking around Dublin in the 90s.”

Niall McCormack, author of Grand Stuff, a book of Irish label art from his own collection of ephemera from 1890 to 1990, says that he too experiences a yearning for the visual aesthetic of his childhood.

“Kid’s comics like The Beano, and the way sweet wrappers were bright but badly printed, and all that kind of Hector Grey classic toys, cheap kids stuff,” he says. “It just had this energy to it.”

The aesthetic that someone is drawn to can be developed in their childhood, which might be why they return to it, he says. “Things from that period, kind of, spark an emotion in you.”

When McCormack curates his collection for a book, like Grand Stuff, it feels to him that he is mining relics of the past, partly for nostalgia, but also to show people that their impressions of the past might be simplistic.

“Nostalgia is a driver, but you’re also trying to create a new narrative about the past, or trying to discover things you didn’t know about it,” he says.

For Grand Stuff, he wanted to show people that there was colour in Ireland during the early 1900s. “Historians generally would think of Irish history in that period as kind of grey and rather bleak. Which to a degree is the case.”

But lots of colour and visuals were used, maybe more than people would assume in their vague impressions, he says. “I’m just trying to broaden out kind of a sense of what the past is in Ireland.”

Kenrick says the quaint or silly ads for products like Guinness that he finds give him an impression of a kind of Dublin he recognises from his childhood memories.

The ads seem like they are tailored towards Dubliners, making Dublin feel like a small town, he says. “Whereas now I feel like ads are probably a lot more aimed at tourists.”

Kenrick finds himself spotting flashes of the past around the city, he says. “I think just my brain’s like, kind of, always a bit in that world.”

A row of old Guinness pint glasses lines his bookshelves.

It feels to him that in the Dublin of his childhood, there were more DIY spaces, more places for punk bands to play music, he says. “It felt like there was maybe more opportunity to do interesting things.”

But it’s not that he thinks living situations were better, he says. “I couldn’t pretend to even know much about what people’s lives were like back then. I don’t compare and contrast about that.”

Arguably, it was worse, he says. He picks up In Dublin and flicks to the classified ads, where there are listings by gay men anonymously seeking company, or for men-only saunas.

“These pages are all ads for gay saunas. But it’s while being gay was still illegal, so they couldn’t say that, so they would say like, men only, strictly confidential, stuff like that,” he says.

McCormack says he’s wary of nostalgia. It can be a trap, tempting people to gloss over issues in the past, and declare that things were better back in the day.

“Even though I’m nostalgic for dirty, smoggy Dublin, I still can realise, you know what, it wasn’t great,” he says.

“I don’t have a view that Ireland is Catholic, or white,” he says. “My idea of Ireland is it should be diverse, and it’s open to everybody.”

But making books like Grand Stuff or City Rocker, says McCormack, is taking an aesthetic from the past and putting it in a new form to share with people.

City Rocker is an amalgamation of the past and the present, through the lens of Kenrick’s personal memories, says McCormack. “It’s also a shared past, because I can remember all those things, the whole aesthetic of it.”

Kenrick says he wanted City Rocker to be silly and light, he says. “I didn’t want it to be like shitting on current Dublin. More than enough people are doing that, for a good reason. I still think there’s something really magic about Dublin.”

It’s hard to put into words why he chooses the ads or images to put into City Rocker, he says.

“I don’t know, it’s to feel like you’re in a fantasy world of what Dublin used to be,” he says. “But to me, it’s just natural, because it’s like, oh, it’s just the stuff that I like.”

Creating City Rocker felt therapeutic, like expressing an inner part of himself, says Kenrick, being able to pinpoint exact things he felt he needed or wanted others to see.

[CORRECTION: This article was updated at 9.49am to correct that one of the magazines that Eddie Kenrick was into in his youth was called Loserdom not Loserville. Sorry for the error.]

Get our latest headlines in one of them, and recommendations for things to do in Dublin in the other.