What’s the best way to tell area residents about plans for a new asylum shelter nearby?

The government should tell communities directly about plans for new asylum shelters, some activists and politicians say.

B?elow where some of the stately homes of Howth jut out over the landscape, where the brambles tussle for space and the Aleppo pine trees mix with the scent of wild garlic, it’s a sheer drop to the Lion’s Head.

A dirt track leads from the main cliff path to a metal fence, where a small parcel of rock sits down the southeast side of Howth Head.

It’s quiet these days, but in decades past the Lion’s Head was a favourite with adventurous swimmers.

It wouldn’t exist as it does, though, if it weren’t for an eccentric university professor, James Bayley Butler, who almost 100 years ago – with gelignite in hand and 100 tonnes of concrete – built a haven of trapezes and diving boards.

On a recent Saturday afternoon, the sun beats down over the bay. In the distance, young lads gather near the Baily Lighthouse.

But there are few passersby here today, and none who have dared the obstacle course to the swimming spot.

To reach the Lion’s Head, swimmers must climb over the metal gate, then abseil 30 feet down the cliff face with a rope. Who erected the gate and who nailed down the rope remains a mystery.

Stephen Peppard, the Howth operations manager for Fingal County Council, said the Lion’s Head is not on the local swimming map at this stage. “As the area is not designated for swimming it does not appear on our radar,” said Peppard, by email.

In fact, in the past at least, it wasn’t even public land. “A lot of the pathways around there are in private ownership and I cannot throw any light on to who may have blocked access,” said Peppard.

Brendan McEvilly, co-author of At Swim which offers a survey of Ireland’s swimming spots, says you would go to the Lion’s Head for different reasons than the more sedate 40 Foot in Sandycove.

Dangerous diving spots are a rite of passage for teenagers in Dublin, the Lion’s Head a “sickly thrill” when he visited recently, he says.

“There was a few different gangs,” says McEvilly. “One of eight teenagers, some with cans near a had-been-lit fire.” Summer is traditionally the season for this.

Stone steps did lead down to the Lion’s Head at one point, says McEvilly. These have since eroded along with many of the features installed by the man who put the rocks on the map.

It was one man who made the Lion’s Head what it was in its heyday.

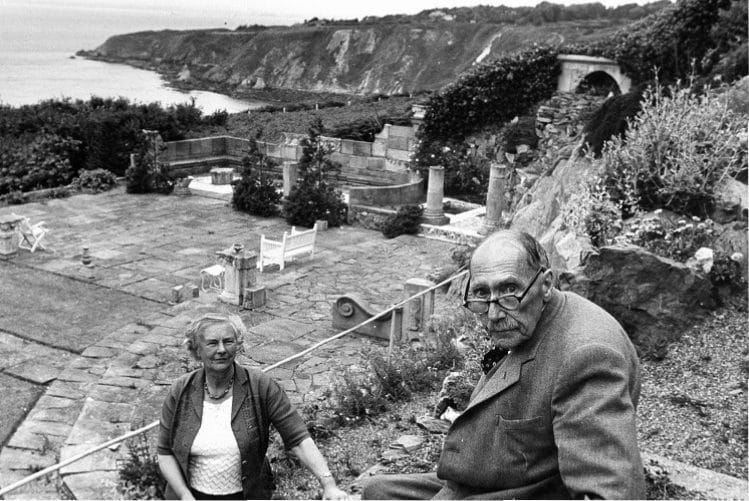

“The Lion’s Head only exists the way it does because of James Bayley Butler,” says Margery Godinho, his granddaughter who used to swim there. “A lot of it he personally did. He used to get students out helping him, but a lot of the work he did on the actual swimming area.”

Some of her grandfather’s do-it-yourself eccentricity may have come from his upbringing, she says. He was born in Secunderabad in India in 1884. His father was based in the city, as head of the British military cantonment.

“Because of the kind of army background there was a certain amount of initiative, and being in India, perhaps making do,” she said.

In his unpublished memoir, Bayley Butler compares the Dublin scenery to the views he remembered from trips to nearby Hyderabad for evenings of entertainment put on by His Highness Nizam VI.

“In fact, when I am returning from Dublin to Howth at night and see the street lights reflected on the sea, it always recalls Hyderabad to me,” he wrote.

Bayley Butler moved out to Howth in the 1920s. Early that decade, during the tail-end of his time as commandant of the GHQ Science Schools at Beggar’s Bush Barracks, he had begun to build a bungalow in the carpenter’s shop.

The problem was that he needed a place for it, a struggle for a while until he learnt of these cliff-side lands. “At last by good chance,” he wrote, “I happened to hear that there was a site available on the Howth estate near the Baily lighthouse lane.”

He leased the land in September 1920 “for a period of 999 years,” about seven acres that stretched to the waters to the south.

He built his bungalow at Glenlion, then later one house and another, over the next 30 years or so. As work continued, he also cut a path through a valley with a stream down the cliff to the Lion’s Head. “I made a series of channels in concrete to carry its water and give a landscape effect,” he wrote.

It was inspired by aqueducts in Madeira, “where the rain from the mountainous regions flows downwards to irrigate the banana and tomato plantations near the coast”.

Constructing the now-faded bathing spot at Lion’s Head was “a most elaborate operation”, he wrote in his memoir.

Bayley Butler drilled the rocks, and blasted them then with gelignite to create the steps down to the low tide.

He did a huge amount of that work himself, says Godinho. “Because of his work in the army he knew about explosives.”

With more than 100 tonnes of concrete, he built seating to hold 100 spectators, which he called The Coliseum. He built a toilet, two dressing rooms, and a bathroom. There were diving stages at different heights, with boards that were 20ft, 22ft and 35ft long.

“There were all kinds of elaborate things: trapezes and ladders, lots of different steps and changing rooms,” says Godinho. “I never saw it working but he had rigged up a boiler where you could have a hot shower or a bath.”

Bayley Butler also attached a jib, a kind of pole, to the Lesser Lion’s Head, the small jut of rocks to the left of the main site. It could be swung out over a nearby gulley, hitched onto a boat below, and used to winch up the boat and its passengers.

A motorboat would ferry boatloads of gravel to the adjoining beach. One day, after loading cement onto the boat at Butt Bridge, Bayley Butler and his boat became stuck in the mud of high tide. “I waded to the shore for sandwiches and thermos flasks of tea,” he wrote.

Godinho said she thinks he did all this largely for his own amusement. “He was kind of a showman so he liked to invite people out to see what he’d done,” she said. “He was quite into acrobatics and various things, he was quite eccentric really.”

In his book, he writes that as a boy in India, he had been trained by Indian jugglers to perform acrobatic feats. Others in the family were unusual too. Godinho’s aunt was a nun with a pilot’s licence, she says.

Evidence of the facilities can still be seen today. There are steps where the diving boards were tacked to rock, and holes where Bayley Butler planted the poles for his jib, and a trapeze and gymnasium rings.

But much of it has been eroded. “Even when I was a child and going out there was always problems with minor landslides and bits of the path would get washed away, or it would have to be redone,” says Godinho.

After Bayley Butler died in 1964 and his second wife sold Glenlion, there was nobody around with an interest in maintaining it. “That part gradually declined and deteriorated,” she said.

Perhaps, it was also a wider sign of the times. As McEvilly sees it the days of the riskier, secluded swimming spots in Dublin are drawing to a close for now. Councils are dismantling the old diving boards for fear of lawsuits, he says.

“I wondered what would happen in the case of an accident,” says McEvilly. “Would you blame the council for letting the steps fall away over time or kids taking their own risk?”

On 5 April 2014 the Irish Coast Guard emergency operations centre received a call before 5pm that two tourists had suffered a fall while climbing the cliffs at Lion’s Head.

When they arrived they found “a male teenager screaming for help and stuck 20 feet from the top in a very precarious position with a risk of a further fall very likely.” The coast guard soon realised that “a second casualty had fallen 150 feet down the cliffs to the beach below.”

Both survived. But it seems unlikely that access to the Lion’s Head will be restored anytime soon.

“I think that culture of, say, a professor taking a group of students is now kind of a romantic notion,” says McEvilly. “I’m not sure if anyone would take it upon themselves now to do that for fear of personal liability.”

The dirt track leads back to the main cliff walk and back out onto Thormamby Road. Another walker, map in hand, navigates the dirt path running along the rusted, metal gate. Below, the Lion’s Head is quiet.

But there’s plenty of advice online for navigating the rocks below, with warnings from those who have tried it out.

“Once you climb over the initial fence, if you make a mistake just there, it could literally cost you your life as there’s absolutely no barrier to stop you going all the way to the bottom,” said one Boards.ie user Spoonface.

“Once you’ve gone down the rope, beware of glass and short metal rods sticking up from the concrete near the high jumps,” they said.

Another user, hardCopy, recalled the times they ventured there. “I’ve some fun memories of the three-bar and four-bar jumps, I never had the bottle to jump The Razor,” they wrote. “Take care on choppy days though, one of my mates lost an awful lot of skin trying to scramble out in rough waves!”

It’s unclear who has blocked off access to the site today. Bayley Butler may well have sympathised with whoever did.

“I think my grandfather would be glad to see that people are still enjoying it, though while alive he didn’t encourage trespassers,” said Godinho. He did devote pages in his memoir to the blight of trespassers.

At one point, inspired by a mushroom farmer from his youth, he put up a sign on the cliff path to deter trespassers, which read: “On and after such and such a date, poison will be laid on these lands.”

“I also put an advertisement in The Irish Times, giving a fortnight’s warning,” he wrote. He had no intention of spreading poison, he writes. But the power of suggestion is strong.

An elderly neighbour warned him one day on the tram he was in trouble with his poison. “Mrs So-and-So has lost two valuable dogs on your grounds,” she told him.

These days, McEvilly says that there are communities of swimmers and divers around Ireland fighting to preserve access to secluded swimming spots.

The Lion’s Head may be too dangerous nowadays, though, he says. “But if I was 15, I would maybe be getting on a bus to get on the Dart to bring cans or a naggin out there and spend the day.”

Get our latest headlines in one of them, and recommendations for things to do in Dublin in the other.