What’s the best way to tell area residents about plans for a new asylum shelter nearby?

The government should tell communities directly about plans for new asylum shelters, some activists and politicians say.

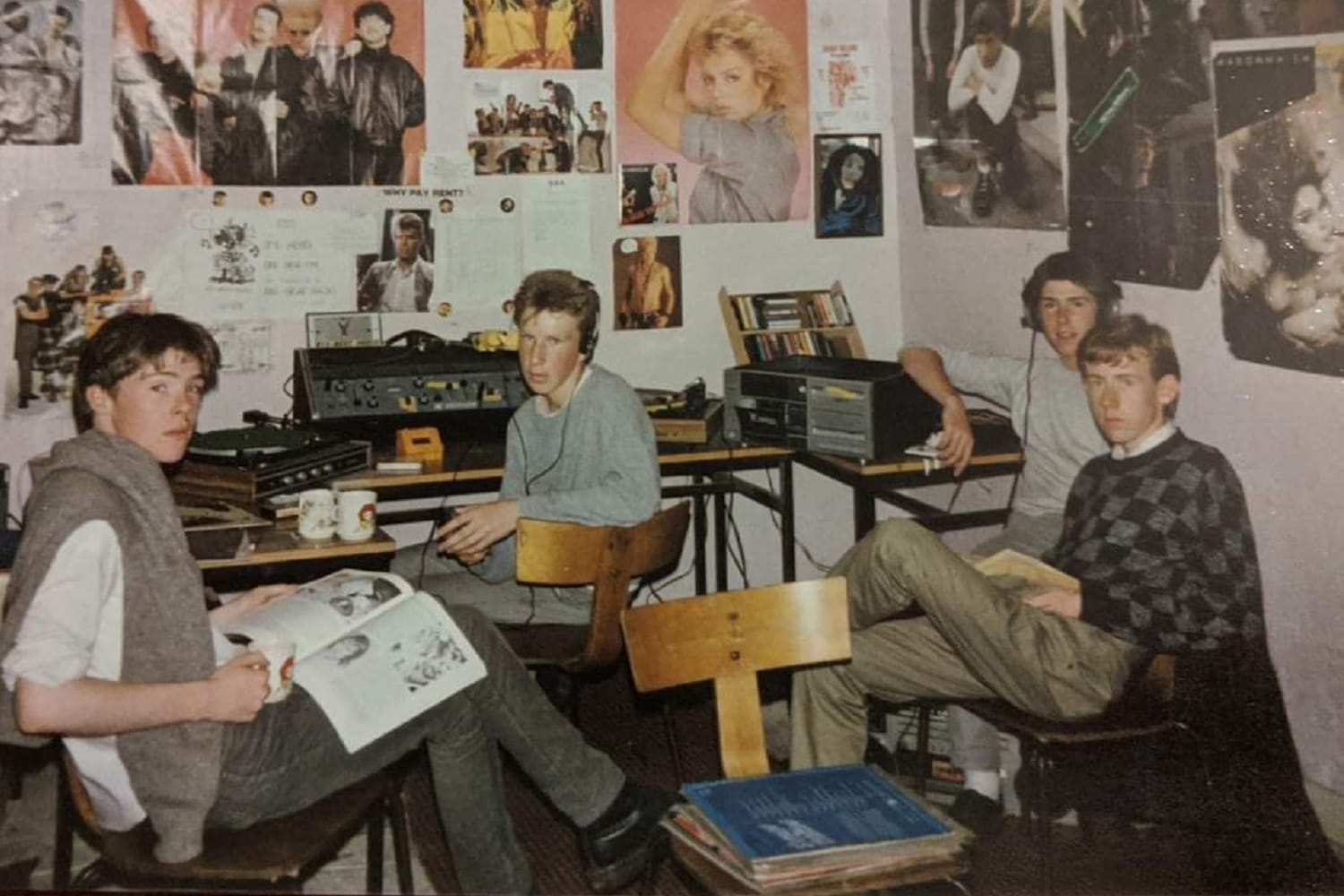

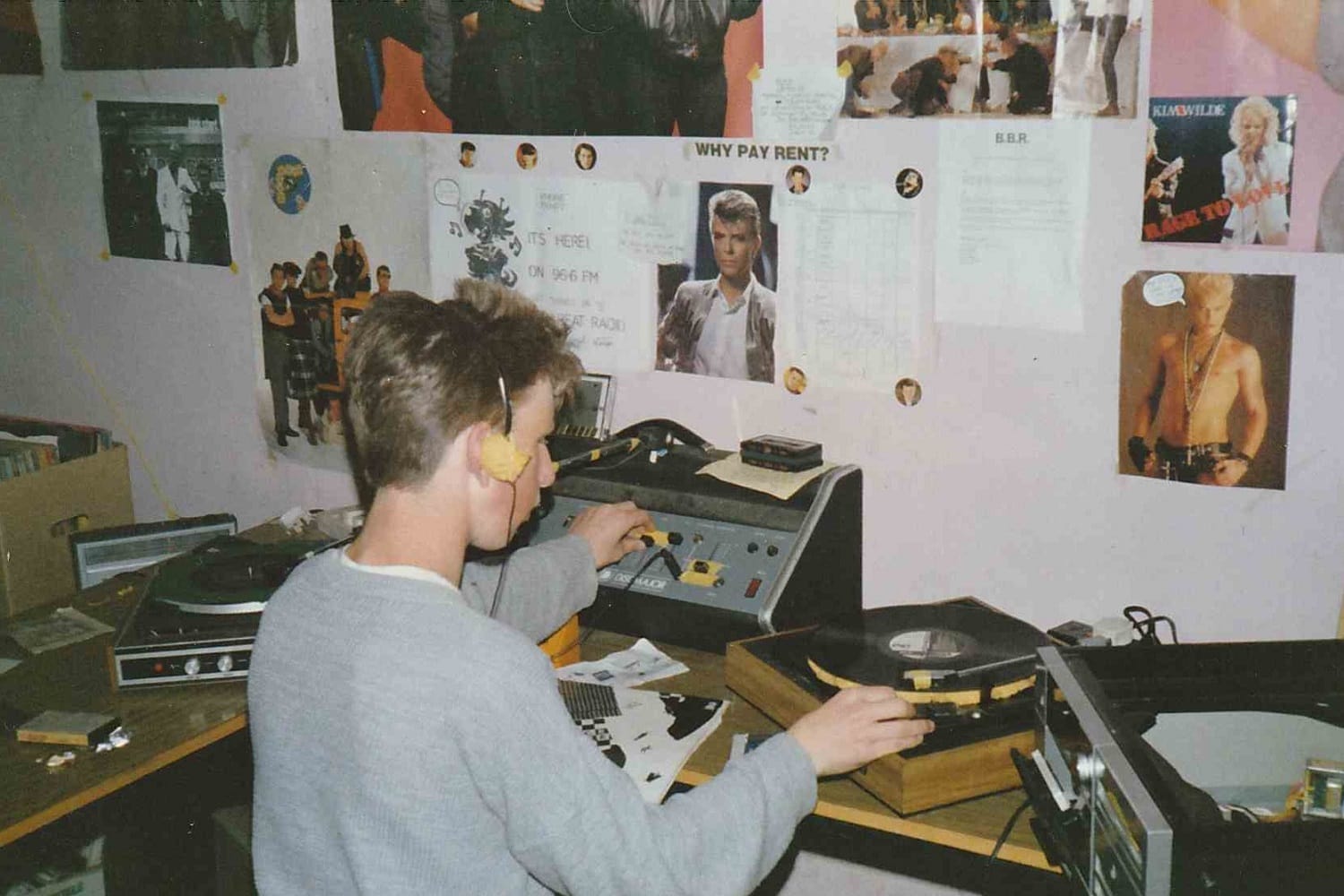

In 1986, it was the hotline to reach the team behind Big Beat Radio, who didn’t want the government to find their transmitter.

Just after 2.30pm on the first day of August, Brian Greene turned off Baldoyle’s Main Street and onto a brick pathway that guides pedestrians onto the Strand Road.

He ambled down the shortcut, hidden behind a small triangular green with palm-like shrubs and a few trees ringed in by a fence of broken branches.

At a timber telephone pole, Greene paused. Just off the pathway embedded in the grass was a slab of concrete. It was cracked and uneven, and its sole notable feature was a pair of Telecom Éireann manhole covers.

“This is where it was,” he said. The former site of an old Eircom phone box, which was stripped out in late June.

Social Democrats Councillor Joan Hopkins said on Tuesday evening that the Baldoyle Wild Towns group had tried to repurpose the phone box several times. “From libraries to bug hotels, but couldn’t get permission due to the location.”

Instead, when the councillor announced its removal on 30 June via Facebook, she said: “It was being used as a bin/loo and really was an eyesore.”

There was once, however, much more to the box.

Decades back, in the summer of 1986, it was used as a line for song requests by the village’s short-lived pirate radio station, Big Beat Radio.

This forgotten detail was pointed out by Michelle Sullivan.

It was a moment in the history of pirate radio and of youthful innovation that deserves to be commemorated, said Sullivan on Monday

“The phone box has been removed, so it’s not a question of preservation,” she said. “But this offers a good opportunity to remember a particular time in Baldoyle history.”

Councillor Hopkins agreed: “It would be great to mark this bit of history/heritage in some way.”

Outside the Baldoyle Community Centre, across the street from the site of the former phone box, Brian Greene orders a coffee at a kiosk.

It was in a small room around the side of the hall that he, his twin brother Dónal, and four friends set up the studio that would become Big Beat Radio.

Now, the studio is a holistic therapy parlour. As the barista prepped his Americano, Greene asked the parlour owner if he could look inside.

Bemused that his parlour was once home to a pirate radio station, the man beckoned Greene into the snug space, the air strong with the scent of incense.

It was an old kitchen when the teenagers rented it, Greene says. “It was damp. It was mouldy and they let us in for a bargain, because we cleaned it up and made it habitable.”

In one corner is a door for the toilet.

That was where their newsreader, a 15-year-old named John Walsh, would deliver the latest stories, local and national, at the top of each hour.

“It would’ve been the summer of the first divorce referendum,” says Greene, “and while we were small, we felt we needed to give the news because that’s what the big stations did.”

Greene steps back outside. He pointed to the rear of the building, which faces onto the bay. There, they mounted a mast for their broadcasts, he says. “We made it ourselves out of aluminium.”

Raheny library had been a vital resource for him and his brother, who taught themselves how to build transmitters and amplifiers from books and manuals, he says. “How to get the wavelength of the antenna cut right, that kinda stuff. The stuff that sticks with you.”

They would copy out diagrams of circuits, Dónal Greene says. “Then if we got a chance, we’d go to Peats on Parnell Street and beg our parents to let us go in and buy the components to build the equipment.”

These days, Brian Greene is the manager at 92.5 Phoenix FM, Dublin 15’s community radio station.

His love of radio started early, he says, remembering a fascination from the age of four. “When I was 14, I started hassling the local community radio station up in Coolock.”

The station was North Dublin Community Radio, later known as Near FM, he says. “And they let me on when I was 15.”

In the summer of 1985, Greene approached his friend, Peter Walsh, who was a big fan of ska. Today, Walsh is a widely reputed archivist of the 2 Tone ska record label, Greene says.

Greene invited Walsh to join his show on North Dublin Community Radio, Walsh says. “So we started a ska show, and then a conversation just bloomed: wouldn’t it be great if we did this?”

They started to plot their own pirate radio station in November 1985, Greene says. “Through the winter, every Friday night, we would have meetings with an agenda.”

The gang of six pooled their record collections, says Michael Redmond, who was one of them. “We all had eclectic tastes, and it just sort of coalesced together.”

Most of the lads had DJ-ed in some shape or form, Dónal Greene says. “We were on the local scene doing youth club discos at aged 14, 15.”

They would journey into the city centre to buy the latest singles in the top 40 chart, says visual artist Brian Hegarty. But “everything else, we cobbled together from what we had; old stereos, mixing desks, record players”.

Hegarty’s older brother gave them a transmitter, says Brian Greene, one that was for FM rather than medium wave.

The plan was ambitious, Dónal Greene says, but really the reason why was simple: “Brian Hegarty and I were probably in school, sitting, talking and saying ‘What are you doing this summer?’ ‘Hopefully not what we did last summer, which was sitting on the wall, kicking our heels.’”

“We weren’t sporty,” he says. “We weren’t gonna join the tennis league. We were just proactively saying, ‘I don’t want do nothing this summer.’”

Big Beat Radio hit the air on 17 June 1986, according to the Irish Pirate Radio Archive.

They went out on 96.2 FM, Brian Greene says. But they couldn’t be sure how far the signal was able to travel.

Ordinarily, somebody had to stay in the studio playing music, Greene says. “We needed a way to put out some continuous sound.”

Fortunately, one of them owned a seven-inch single called “I am the Beat” by the band The Look, he says. This particular record ends on a locked groove. The song loops until the needle is lifted.

“It ends with the band just saying: ‘beat, beat, beat …’,” he says.

They stuck the single on a record player and mounted their bikes, carrying a radio to see how far their signal travelled, he says. “We were going about two and a half, three miles, and that was it. The radio station was born into existence.”

Each host chose a pseudonym. Michael Redmond was Tony Johnson. Brian Greene was Bobby Gibbson, says Hegarty. “I went under the name Lionel Grunt, don’t ask me why.”

Being kids who were not sending out political messages, the threat of Gardaí breaking up their pirate broadcasts was slim, Hegarty says. But they were still ready.

“We had procedures, like putting transmitters in the bag and throwing it out the window,” he says. “There were protocols, and even at that age, we were aware.”

Nobody ever doorstepped them. But a local employee in the Department of Communications once approached Dónal Greene on the street, Greene says.

“He said, ‘I know what yis are up to. It’s okay, but I’m giving you one warning. Your transmitter, we know its origins. It was an ex-Sinn Féin radio transmitter,’” Greene says.

“He was able to tell us that,” Greene says. “We didn’t know any of that.”

A radio show needed to be able to take requests. But they didn’t want to be shut down.

Hence the idea of using the phone box, says Dónal Greene. “The post and telegraph company were the physical arm of the Department of Communications, and they were doing the raiding.”

“Using a real phone line going into the studio was a no-no,” he says. “So we had a proxy.”

The box taken out recently was about 100 metres down the road from the hall. Listeners could put in song requests at the number 32-22-15, according to the Irish Pirate Radio Archive.

From 9am until 9pm, the station was broadcast. Two people manned the box during each show, Dónal Greene says. “It was the six founders and maybe another 10 people around the station, who did shows themselves.”

“When we called out the number, the phone would be hopping,” he says.

Big Beat was on the air for seven weeks. It wrapped up on the evening of 8 August.

There was a split amongst the six founders, Brian Greene says. “We had a musical difference. Three of us went one way, three went the other and into Temple Bar to set up record stalls.”

He and Peter Walsh went on to found Centre Radio that December.

Dónal Greene left radio until 1992, when he launched Radioactive, he says. “It launched in and around the X-case and became a political pirate. Non-pop was the musical genre.”

The final Big Beat Radio show was eventually archived on the Irish Pirate Radio Archive, the station wrapping with Simple Minds’ “Don’t You (Forget About Me)”.

As the 1985 hit reached its uplifting chorus, Brian Greene signed-off: “Big Beat Radio has come to a close, the time is now six o’clock, goodbye.”

The bells from St Laurence O’Toole Church clanged over the music, before both collapsed into white noise.

Sure, it was all short-lived, Dónal Greene says. “But when you break it down, we actually just created a community space for our friends to hang out, talk, share ideas.”

“To give youth a space at that age is very important,” he says.

“We had to make it for ourselves,” he says. “But to give them that, to do whatever they want, changes societies because you take on a lot more responsibility when you have that freedom.”

Get our latest headlines in one of them, and recommendations for things to do in Dublin in the other.