What’s the best way to tell area residents about plans for a new asylum shelter nearby?

The government should tell communities directly about plans for new asylum shelters, some activists and politicians say.

Martin Keane’s plan to revive the shuttered Iveagh Markets promises to bring new businesses and customers to the Liberties – and perhaps gentrification.

At a table in Temple Bar on a recent Thursday afternoon, I sit across from one of Ireland’s richest men: self-made millionaire Martin Keane. His grey pinstripe suit and pink shirt fit the warm weather.

Though he is not a common household name, the 66-year-old has been buying up property throughout Dublin for the past 40 years. You’ve likely had a pint in one of his city-centre businesses.

We sit on Anglesea Street in front of his pub, Oliver St John Gogarty’s, as the sounds of traditional Irish music, stag parties and seagulls float around us. Just down the road is another of Keane’s ventures, Bloom’s Hotel; in fact, from hotels to hostels, he owns most of the businesses along this strip.

Ignoring his ever-present earpiece and the buzzes of his retro Nokia 6310i, without any “ums”, “ehs” or “wells”, he discusses his current project, which has been in the works since the 1990s: the Iveagh Markets in Francis Street.

“I was very interested in it,” says Keane, “because I knew it from my childhood.”

Lying unused since 1999, the iconic Iveagh Markets have become derelict. Weeds protrude through the door cracks, and cans and other litter have accumulated behind the closed gates. Refurbishment of the protected structure is estimated to cost around €26 million.

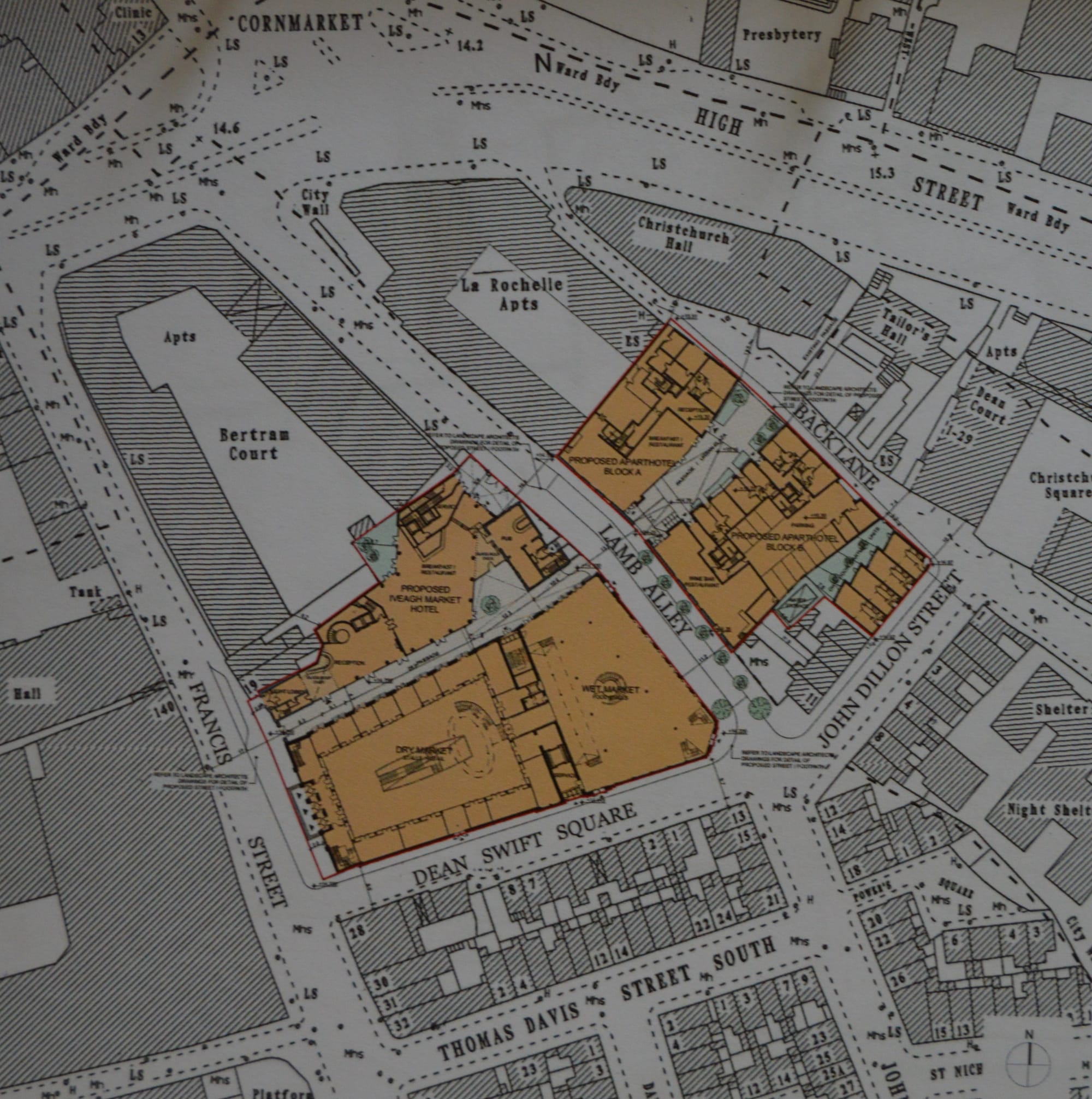

That’s not the only investment that Keane has planned for the area. As well as the Iveagh Markets, he’s investing €64 million to develop surrounding properties that he has bought over the years. “They will all be connected together,” he explains.

A four-star hotel and apartments and houses available for rent by holiday-makers – Keane is turning the markets into a Mecca for tourists.

Plans also include bars, restaurants, a nightclub, a distillery and a brewery. Are the Iveagh Markets set to become the epicentre of Dublin’s new Temple Bar?

Dublin City Council sought a private developer to restore the markets in 1996 and Keane – who nostalgically remembers cycling there to buy fresh fish – won the competition for a 500 year lease with his plans for the site.

Progress was delayed by a dispute over ownership between the council and the Iveagh Trust. (Edward Guinness, first Earl of Iveagh, originally built the markets in 1907 to house street traders.)

Then, archaeological work took eight years to complete. During this setback, Keane bought properties surrounding the markets and developed plans for them as well.

The building to the left of the markets, formerly a delousing house, will become the 97 -bedroom hotel and will house the nightclub, distillery, brewery and bar, as well as a sixth-floor penthouse with panoramic views of Dublin that will be “semi-public”.

It will have a better view of the city than the Guinness Storehouse, says Keane.

The lane between the two buildings will be pedestrianised. Behind the markets, Lamb’s Alley will feature a flower market and there will be two blocks of 84 apartments and some houses, which will be serviced by the hotel staff and will cater to tourists. Keane calls it the Aparthotel. Here, there are also four more retail units.

Not long after planning permission was granted for all this in 2007, the financial crisis came and “the ass fell out of the banks”, as Keane puts it, resulting in a shortage of financing for the development.

Though Keane admits that the recession had a terrible effect on his interests – the values of some his properties dropped by 60 percent – none of his assets had to be taken into NAMA.

Now the site on Francis Street is debt-free and refinancing for the €90 million development has begun. All the archaeological work is finished, health and safety work is being done and, next, the site will be restored brick by brick.

This isn’t Keane’s first refurbishment. Since making money on his first successful business in the 1970s, he’s been buying and doing up properties.

He has a particular liking for Georgian buildings, having bought some in Ballsbridge, Merrion Square, Fitzwilliam Square and Pembroke Road.

He gives the impression that restoring historic properties is a hobby of his. He still lives in the estate house near Ranelagh that he bought and restored nearly 40 years ago.

This home remains his favourite renovation job to date. “It was completely derelict and it was 12,000 square feet and I restored every bit of it. I got great joy,” he says.

He is also proud of restoring a house that used to belong to the British Legion in Merrion Square. “It was in quite rough condition when I bought it,” he says, “but I brought it back; all the ceilings, all the Georgian design that was in it at the time.”

Keane’s passions go beyond property. He loves most things Irish, particularly art, and wants to showcase that in this development.

“Everything in the hotel will be of an Irish nature,” he says, in his gravelly Dublin accent. “Literally, as far as we go, down to the bed linen, cups and saucers, we’re going to try and source it and have it completely Irish.”

In Keane’s vision, the markets are a haven for Irish crafts, fashion, food and art. He goes back to the image of buying fish from the market, saying that he wants customers to be able to buy oysters, smoked salmon and chowder to bring home or eat on the spot.

“It will have everything that you can think of that’s Irish,” he says, comparing it to the annual RDS bonanza, Showcase: Ireland’s Creative Expo.

He confirmed his first tenant for the markets after the Doll Store, Hospital and Museum closed its doors in the Powerscourt Centre last month. He expressed an interest in saving the famous business – which has been around since the 1930s – because he remembers it from his youth and feels it’s a part of Dublin’s history, says owner Melissa Nolan.

She’d never met Keane, but received a call from him “completely out of the blue”, which stopped her from selling the store’s cabinets.

The Iveagh Markets’ mezzanine will feature studios for artists, craftsmen, jewellery makers, sculptors, painters and potters, according to Keane.

“They will be able to sell direct to the people of Dublin or to people who are visiting, and they can go and see them actually operating in it,” he explains.

Keane is determined to sell nothing but Irish produce in the Iveagh Markets when they reopen in 2019. He has plans to bring in his own customers from outside the Liberties, he says, adding that his hub will target tourists and businessmen.

In its heyday, the Iveagh Markets was a grand building with a beautiful ceiling that sold “everything from a needle to an anchor”. The stalls were piled high with every type of clothing, from suits to Communion dresses, and the balconies were crammed full of furniture, recalls Catherine Keating, who worked in the markets as a child, with her Aunt Bessie and Nanny Sarah.

Keating compares the markets to today’s shopping centres in that they sold everything you could need: clothes, shoes, fruit, veg, meat and “fish straight from the sea”.

“It was all fresh and you could even get pigs’ legs and ox tongues, which were delicacies at the time,” she says with a smile.

She fondly remembers the buzzing atmosphere of the markets; mothers would bring their newborns to introduce them to everyone.

Saturdays were busiest, with farmers coming from the countryside to buy suits and shirts, she says. It was known for its bargains, and all the clothes were second-hand. You could buy just a shirt collar if you wanted to save a few quid, a practice now long extinct.

The hat stall had every type of hat imaginable, says Keating who remembers the woman who ran the stand: “If someone tried on a beret, she would do a French accent.”

Now selling clothes in the Liberty Market on Meath Street, Keating says the Iveagh Markets hosted some lovely people, “salt-of-the-earth-type of people”, as she puts it.

She is happy to see the refurbishment of the Iveagh Markets and hopes it will help revitalise Francis Street, which was once a booming antique quarter.

But she doesn’t think the markets will ever be the same. “I don’t know if you would find second-hand clothes . . . and I don’t think you would get the characters back,” she says.

Would she consider opening a stall there when it reopens? She expects it would be units rather than stalls, and that it would be too expensive.

This sentiment is echoed by the other traders here. Though everyone is delighted to see the markets being refurbished, there are concerns that it will be too expensive for local vendors and consumers.

If the price of a pint in Oliver St John Gogarty’s is anything to go by, then these concerns are probably justified. At €6.95 for a pint of Heineken and €5.95 for a pint of Guinness – or after midnight €7.30 and €6.30 respectively – not many local Dubliners would be paying these prices.

But business owners on Francis Street seem excited for the markets to reopen, and hopeful that some of the benefits will flow their way through a boost in sales.

“I’d love to see it opening,” says Alexandra Pearle of Euricka Antiques. “It would bring a tremendous amount of business to the area.” She’d like to see more ATMs, a decent café, a newsagent, and tourists coming through.

Dublin City Council has already planned to redevelop Francis Street with extended stone footpaths, new lighting, pedestrian crossings, trees and public art.

Both Pearle and her neighbour, Martin Fennelly of Martin Fennelly Antiques, dismissed any worries about rising rents or competition from the markets.

“It is a disgrace that an iconic public building ever fell out of public hands, but at least it’s in the capable hands of Martin Keane,” says Fennelly.

He acknowledges that rents may go up, but this would go hand in hand with an improvement in business.

Pearle welcomes the competition, hoping it will weed out the likes of charity shops and off-licences, and restore Francis Street to its former glory as a street for antiques and artwork.

John McGovern of the Dean Swift was also positive about the concept. “It will bring more footfall to the area, more rejuvenation,” he says.

The Francis Street area has gone a bit stale, he says, and the redevelopment will give tourists an alternative to Temple Bar.

Some major investments are planned, or underway, in Dublin 8: the new Guinness site, the new children’s hospital, student accommodation, the Dubline tourist trail and three new distilleries. Though these are great for jobs and boost other businesses in the area, more developments in the area provide services to tourists than to the local residents.

During the planning stages of the Liberties Local Area Plan, the public consultation in this section of Dublin 8 highlighted a number of concerns for locals. Topping the list was a lack of food stores, community facilities, green spaces and street lighting.

While all types of food will be available, the Iveagh Markets – once known for affordable prices – will likely prove too expensive for many locals to do their weekly shopping.

Gentrification is a term rarely heard of in Ireland, but developments like this run the risk of excluding or even pushing out local residents as prices are pushed up.

Dublin has seen the gentrification of areas like the Docklands and Rathmines, but in the Liberties it is different because this is more likely to be caused by the area’s popularity among tourists rather than among Dubliners.

A study of the Vieux Carre, the French Quarter in New Orleans, by Professor Kevin Fox Gotham traced the “tourism gentrification” that took place there, a type of gentrification that’s commercial, as well as residential.

After the economy in New Orleans struggled for decades, things began to pick up after the 1980s due to growth in tourism. The development of entertainment and tourism in Vieux Carre brought more upscale and affluent people to the area, attracted big retail chains and saw an increase in property prices.

This, in turn, priced out working-class residents, creating a less-diverse population, pushing out hardware stores and independent pharmacies, and forcing small antique and art dealers to move to where rent was more affordable.

“Designer bars, chain restaurants and tourism-oriented souvenir shops have gradually replaced former working-class corner cafés and food shops,” the study says.

Though this example is extreme, gentrification could easily happen in the area around the Iveagh Markets. Temple Bar was meant to become the city’s cultural and creative quarter – and still claims to be – before pubs and nightclubs were allowed to take over every available space.

Temple Bar planners aimed to recreate London’s Covent Garden, but the reality is far from it. Keane too cites Covent Garden as his vision. Keane is trusted with the restoration of the Iveagh Markets – and rightly so, given his track record.

But with pubs and breweries already rooted in the plans, it wouldn’t be a shock if the Iveagh Markets became an upscale extension to Keane’s strip of Temple Bar.

Get our latest headlines in one of them, and recommendations for things to do in Dublin in the other.