What’s the best way to tell area residents about plans for a new asylum shelter nearby?

The government should tell communities directly about plans for new asylum shelters, some activists and politicians say.

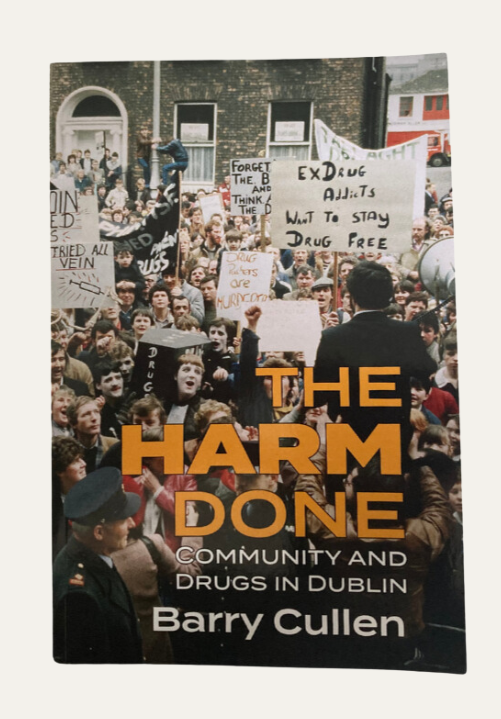

A Dublin social worker “reveals the challenges, failures, and conflict in the effort to build a community model to manage and address drug problems in under-resourced communities”.

Barry Cullen considers himself to be an “accidental drug worker”.

In the early 1980s, after taking on the role of social worker with the Eastern Health Board, he was assigned to Dublin’s south inner-city. The heroin epidemic was spreading through working-class communities, and this was to be Cullen’s first introduction to the devastation it caused.

The Harm Done: Community and Drugs in Dublin revisits the emergence of the opiate culture in Dublin and examines the local and national response from the perspective of someone who has dedicated their working life to the communities most affected.

One of seven children, Cullen had a supportive upbringing where education and independence was encouraged. His parents were actively engaged in many strands of Ballyfermot parish life.

Through their involvement in the Ballyfermot Community Association, they continuously campaigned for youth and recreational facilities, while producing newsletters and organising outings for local teenagers.

No doubt, the author was inspired by the industry of his parents, and their strong community involvement must have played some part in his venture into the field of social work.

Growing up in Ballyfermot also played a part, where he had first-hand experience of the problems that faced heavily populated towns with a serious lack of facilities.

Cullen attended his first protest march at 15 years old, a campaign supporting a fair differential rents scheme, whereby the rent on all local-authority houses and flats is dependent on the income of the tenant.

In the 1980s and early 1990s, he joined many groups that rallied against the governments’ stance on drugs. The predominant ideology the government followed at the time was one where abstinence is the leading method to tackle drugs.

These groups emphasised that a much more holistic approach to treatment was needed, and re-enforced the fact that socioeconomic background plays a significant role in the growth of drug problems.

After studying at Trinity College Dublin, qualification took Cullen to St Teresa’s Gardens flats in the Liberties. It was Teresa’s Gardens Development Committee who first noticed the influx of opiates into the area.

Young people attending an outreach club were showing sudden mood changes and they began to distance themselves from volunteers. In a noticeably short space of time, the main drug of choice had shifted from cannabis to heroin.

In the past, when it came to issues in flat complexes like St Teresa’s Gardens, Cullen tells us that the general approach from the health board appeared to be a “farming out” of services to a religious third-party, creating a buffer between the health board management and the actual issue.

But the drug issue would not be solved by a small monetary grant and a belief in God. With government slow in implementing a strategic policy, local communities were compelled to fight back.

Meetings were planned, expert speakers were invited, and people were given the opportunity to raise concerns and share experiences. Continuously, questions about the pushers and dealers came to the fore, and the fact that authorities were doing little to stop them.

Members of the community began to “keep all drug dealers under surveillance”. Perimeter patrols were introduced and outsiders who came looking for drugs were turned away from the area.

Dealers were invited to these community meetings and warned to end their illegal activities. On some occasions, when the dealers refused to stop, they were forced out of their homes and out of the area by the local community.

The author tells us how the role of community has always been a driving force for him.

Historically, community groups have tackled issues with healthcare and childcare, as well as championing women’s rights in a time when the marriage bar was in full effect and women were vastly underrepresented in the labour market and beyond.

A multitude of important agencies were born from the work of community groups, such as the Combat Poverty Agency and the Local Drug and Alcohol Taskforces.

But the author also stresses that the concept of community is complex and can be contradictory at times because you cannot assume an entire community has the same goals or principles. What is clear is that communities need funding and investment for the greater good of the whole country.

In Cullen’s experience, he would advise against communities entering the arena of broad political activism. Community development works best “where the aims and purpose are realistic”. This “meaningful and tangible” approach transfers down to how the author approaches the issue of drug abuse.

Aligning with his background in social work, he focuses on the individual in relation to four principal areas: prevention, counselling, treatment, and rehabilitation.

The Harm Done reveals the challenges, failures, and conflict in the effort to build a community model to manage and address drug problems in under-resourced communities.

It touches on the issues facing working-class communities over the past 40 years, from the influence of religious-owned institutes to the national policy on drugs and treatment, and the general lack of understanding and negativity toward large urban council estates, a negativity often perpetuated by sensationalist reporting.

A true insight into the work carried out at local level, Barry Cullen’s book is a fantastic read and resource for educators, community leaders, and those who value the idea of community.

Get our latest headlines in one of them, and recommendations for things to do in Dublin in the other.