What’s the best way to tell area residents about plans for a new asylum shelter nearby?

The government should tell communities directly about plans for new asylum shelters, some activists and politicians say.

Nobody asks Julian Cosby back to Dublin. Each year, he has simply returned.

Julian Cosby bellows in his BBC accent from above.

“Mind that gap as you’re coming up!” he cries, ascending the bell tower of St Paul’s on Arran Quay. “Now when you reach the top, grab on to that metal shaft.”

Despite his arthritic 71-year-old frame, the horologist moves swiftly up the series of ladders, and leaps across obstacles with ease.

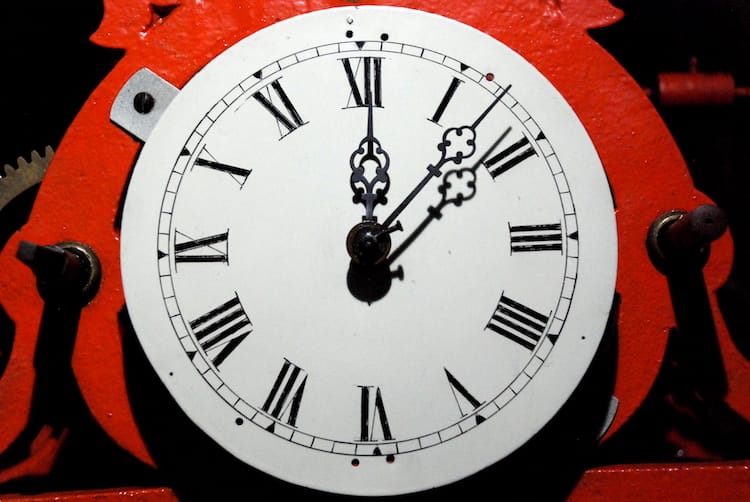

It’s five floors to the church’s clock room, where, for most of the morning, Cosby has been servicing its original timepiece, linked to the tower’s four clock faces, which overlook the city.

He’s back in Dublin for two weeks to service, and to save, the city’s remaining antique clocks. “They’re not just clocks, though, you see,” says Cosby. “They are scientific instruments and they are our inheritance.”

Raised in an Anglo-Irish household in Stradbally in Co. Laois, Cosby has lived in Wiltshire in England since 1990.

He studied agricultural engineering in the late 1960s, and later antiquarian horology in Sussex, where he opened his own workshop in Marley Park in 1980.

Around 1981, he began to notice a pattern emerging: Dublin’s oldest clocks were either not working or were being replaced with electronic mechanisms. That observation prompted a mission that lead him to where he is today.

Wind whips between the clock tower’s slats, which are caked in pigeon guano. Cosby, broom in hand, pokes his head through an open trapdoor to the tower’s bell room, lit only by faint light that filters in through the slats. A tang of oil and white spirits, smeared across his white coat, mixes with dust rising from rotten floorboards.

“For 35 years, and to this day, all people are interested in is sticking up an electric clock,” says Cosby sternly. His white handlebar moustache twitches. “I’ve nothing against electric clocks, but these are our inheritance. So that started me off.”

Cosby’s first job in Dublin was in 1981 at Royal Hospital Kilmainham, where he worked to restore the building’s original 18th-century clock mechanism, which still ticks today.

In 1985, he “saved” clockmaker Alexander Waugh’s 1818 mechanism at St Brendan’s Psychiatric Hospital in Grangegorman. Hospital authorities were about to bin it, after they discovered it in the clock tower.

It’s difficult for the layperson to understand this work, says Cosby. Clocks have incredibly complex features, dozens of tiny intricate parts all moving in sync, each one dependent on the other.

These timepieces are, therefore, historical artefacts of engineering and design, “part of our inheritance”, Cosby repeats several times.

Yet most people only see a clock face telling them the time. Few see the detail.

And few seem to care, says Cosby, who returns to Dublin every January to service the 22 clocks he has saved.

“This clock, up here, is a very good example of a wind-driven remontoire,” he says, pointing towards the ceiling as we near the top of the clock tower.

Terms like “remontoire”, a mechanism to ensure accuracy, come hard and fast as Cosby bounds from one creaking room to the next.

The names of great clockmakers – John Harrison, George Booth, John Crosthwaite – recur in conversation. “Gilding”, “flat-bed”, “quarter chime” and “skeleton dials” – the lexicon of horology.

Cosby climbs through the trapdoor into the bell room. “The higher you go, the colder it gets,” he says.

After St Paul’s, he is off down to Trim, Co. Meath, in the hope that one preserved timepiece in the village is still there.

Nobody asks Cosby back to Dublin. Each year, since 1990, he has simply returned, servicing clocks wherever it’s needed.

“He’s a gold mine of a guy and a dying breed,” says James Rooney, of the Grangegorman Development Agency. The agency allows Cosby in each year to check up on Waugh’s 1818 mechanism.

“It’s a clock of some historical significance, so we set about ensuring its proper maintenance,” says Rooney.

Each year, he says, Cosby arrives to check if Waugh’s clock keeps proper time. “It’s more than just Dublin, though,” says Rooney. “He tours around wherever they are.”

Cosby, however, isn’t always accommodated upon his return.

“Here we are,” the old horologist says, entering the clock tower’s top floor through the final wooden trapdoor.

The climb is complete. Strips of Dublin’s landscape are visible through the the slats: Smithfield, the Liberties, and the Liffey. Something ticks.

In the centre of the room, there is an orange wrought-iron clock in a wooden cabinet. The hand-painted dials turn slowly. A small golden plate, pinned to the cabinet door, reads “J. Cosby”. One of his own creations.

“We have, up here on our shoulders, what’s known as a head,” says Cosby, suddenly, practical and matter-of-fact. “But today you’re not allowed to use it.”

In his race against time to save Ireland’s antique timepieces, Cosby frequently encounters issues around health and safety. At times, he is denied entry to service historic timepieces in historic buildings because he refuses to buy a safety certificate.

“Health and safety won’t stop you falling off a ladder,” says Cosby. “Your head will stop you falling off a ladder.”

He presses on but each year the obstacles – age, time and bureaucracy – become greater.

“I’m hitting my head against walls here trying to save these clocks,” he says. “You’re up against authorities.”

Go electric, by all means, but antique timepieces in Ireland’s historical buildings, no matter their condition, are worth saving, says Cosby.

“I’m just trying to improve timekeeping,” he says. “You have to save the good and the bad.”

The climb down comes easier. As he descends the church steps, though, Cosby’s arthritis becomes apparent, his torso bent double.

He points with his broom to a pile of dirt and dust in the corner and smiles.

“I leave a small pile there each time I fix a clock,” he says. “So when I come back next year, if it’s still there, I’ll know they haven’t been looking after it.”