What’s the best way to tell area residents about plans for a new asylum shelter nearby?

The government should tell communities directly about plans for new asylum shelters, some activists and politicians say.

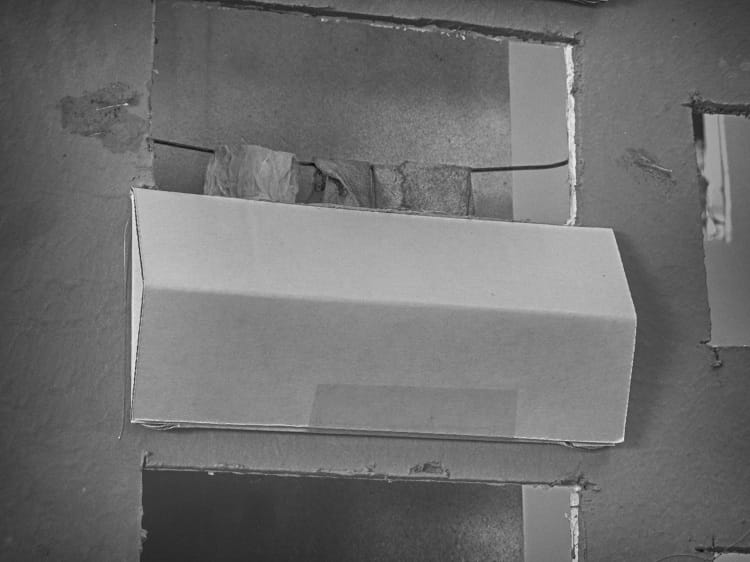

This documentary weaves together candid footage and interviews to build up a story of the regeneration, exploring what was lost as the towers came down.

One of the many projects connected to the regeneration of Ballymun was an effort to collect oral histories from the local community.

Historians were brought in, and they worked with local residents to record stories of the iconic suburb, but the results were never published and promoted, says film-maker Turlough Kelly.

As he shows in his new film The 4th Act, through interviews with those involved, officials at Ballymun Regeneration Limited didn’t like the direction the project had taken.

“They lost that ability to portray the past in a particular way,” he said. To Kelly, that showed how seriously officials saw their role as being the prism through which the past had to be interpreted.

This is just one of the threads in the film, which will be screened this weekend as part of the Audi Dublin International Film Festival.

It weaves together poignant and candid archive footage to build up a story of the close-to-€1- billion regeneration that explores memory and power, the relationship between communities and the state, and what else was lost as the towers came down.

At first, it was going to be a series of short drama films, says Kelly. The crew had access to Joseph Plunkett Tower, the last to go up and the last to fall, and the shorts were to be centered around that.

“I think we realised quite quickly that to do any justice to the topic it needed to be a documentary,” he said. In the end, the film took three years.

Kelly’s background was in sports journalism, he said.

He came to film-making through Dublin Community Television. There, he wrote and directed Dole TV, a current affairs and sketch show, presented by Dean Scurry.

Most of the crew who worked on The 4th Act made their start at the community television station. “For the brief window that is was semi-funded, which it isn’t anymore,” he said.

First and foremost, The 4th Act is a film about memory and the denial of memory.

“People feel quite alienated from the process of remembering. Remembering those good and bad things about their childhood and being brought up in Ballymun,” he said.

In part, that was because others were telling their stories, but it was also a result of the changes that were going on in Ballymun, and the way in which Ballymun Regeneration Limited controlled the narrative.

“It allowed them to portray the past in a very particular light and once you do that you have a free hand to interpret both the past and the future,” he said.

Kelly sees echoes of that process in the possible plans to rebrand and regenerate the north-east inner city.

As Kelly sees it, the tensions between the needs of the state and its masters – who Kelly sees as development and private capital – and the needs of the community, are incompatible.

“Those power relations are never going to resolve themselves in a way that is favourable to the community. That’s just the way our society works,” he said.

At one point in the film, a timeline illustrates how the many community organisations in Ballymun were gradually extinguished.

The loss of community is also at the heart of the film. “It’s so raw and it’s so apparent,” he said. “It’s like the core has been scooped out of the community in a way that everyone can see.”

People are aware that they have lost those networks of self-organisation and dissent, he said.

While some might argue that this was part of a wider trend of atomisation in post-industrial societies, it was felt acutely during the regeneration process, said Kelly. “It’s one of the biggest sore points.”

“They replaced a lot of the fairly militant local community tenants’ associations and things like that with forums that they funded and effectively controlled,” he said. “There are no representative bodies in Ballymun anymore.”

Part of the film critiques the official arts-based strands of the regeneration, through a look at the outcome of the oral histories project, or a sponsor-a-tree project.

As Kelly sees it, they were either tacitly or explicitly given the task of presenting a particular view of the new Ballymun.

But he doesn’t directly look at issues around the portrayal of Ballymun in wider media, in films, or on television.

“I never got that het up about that because I know how lazy a lot of mainstream cultural practice is, and Ballymun was really just a placeholder for a particular stratum of working-class life,” he said. “If it wasn’t Ballymun, it would have been Darndale, or Tallaght, or wherever.”

He approaches that debate in a more circuitous way in the film, and hints at the importance that narrative had to persuading people that the regeneration had to go the way it did.

“I think to some extent it played into the hands of the regeneration company in that preexisting negative reputation was a very powerful tool for persuading people that the way they had been living was wrong, and unsustainable, and needed to be changed in a very fundamental way,” he said.

On the shelves of Kelly’s workspace in Ballymun are hundreds of video tapes from the last 30 years or more of life in the community.

Sourced from local residents by what is now called Ballymun Communications, and used to be Ballymun Media Co-op, the footage brings life to the film.

“Essentially, it was just local people who felt misrepresented or unrepresented by the mainstream media and decided to do something about it by depicting their own lives, by capturing the essence of their own struggle,” he said.

“What I hope the film can do is sort of unleash some of that. Because a lot of it never made it’s way into the public consciousness. It just wasn’t seen.”

In a way, the footage is more than just a catalogue of life in a corner of Dublin. It is there to vindicate the struggle of those who are depicted. “That truth can’t really be suppressed while all that footages continues to exist,” he says.

“It’s melancholy in some ways to look at the effort that went into, and the sincerity with which people tried to depict the overlooked realities of their lives and simply weren’t heard,” he said.

While The 4th Act will be screened this weekend, Kelly says that he hopes it won’t stop there. He would like to see it shown in other communities facing similar processes, who need to arm themselves with information to see through the smoke and mirrors.

“There’s an awful lot of money being thrown at attempting to make you doubt your own history, or second-guess your own instincts,” he says.

It’s about reminding people that they need to have their own instruments of self-organisation and defense. “That’s my main aspiration for the film,” he said.

The 4th Act will be screened this weekend as part of the Audi Dublin International Film Festival, on Saturday 25 February at Cineworld and Sunday 26 Feburary at the Lighthouse Cinema in Smithfield. You can book tickets online.