What’s the best way to tell area residents about plans for a new asylum shelter nearby?

The government should tell communities directly about plans for new asylum shelters, some activists and politicians say.

Sé Merry Doyle’s intimate film is a plea by Simon Walker to preserve modernist structures in Dublin designed by his father, architect Robin Walker.

You might have seen architect Robin Walker’s buildings around town, even if you haven’t realised it. There’s the the old Bord Failte headquarters on Baggot Street, the Restaurant Building at UCD’s Belfield Campus and Wesley College in Balinteer, to name a few.

In the new documentary Talking to My Father, which opens at the Irish Film Institute on 16 October, Walker’s buildings are brought to the screen by director Sé Merry Doyle, with the help of Walker’s son, architect Simon Walker.

In a way, the film is a plea from Simon to preserve and celebrate these buildings, as he strives to explain the ideology that led his father, an influential modern architect, to shape them as he did.

It’s an intimate film.

It opens with Simon standing on the frame of his bike to sneak a peek at his boyhood home. The home on St Mary’s Lane, only a stone’s throw from the Grand Canal, is in the heart of the city, but takes no part in it, hiding behind a high retaining wall.

The home, with its clean minimalist interior, was designed by Walker for his son, Simon, and their family. Simon stands in a bright and well-ordered courtyard, and reminisces about the many happy memories that live there.

In the late 1940s, Simon’s father was mentored by Swiss-French architect Le Corbusier, who is seen by many as the godfather of modern architecture. Walker later worked in Chicago under another giant of the field, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe.

To urbanists, Le Corbusier is perhaps best known for his Plan Voisin, which sought to tear down a huge segment of Paris’s Right Bank and its complex slums, in favour of well-ordered tower blocks interspersed in green fields.

Most are thankful that this plan never came to fruition; it would have ripped up and destroyed some of Paris’ most enchanting neighbourhoods, including the third and fourth arrondissments, that are full of intimate winding streets and stories.

Back in Ireland, Simon introduces us to his father’s many creations around the country, explaining that, in them, he sees a form of his father’s love for him.

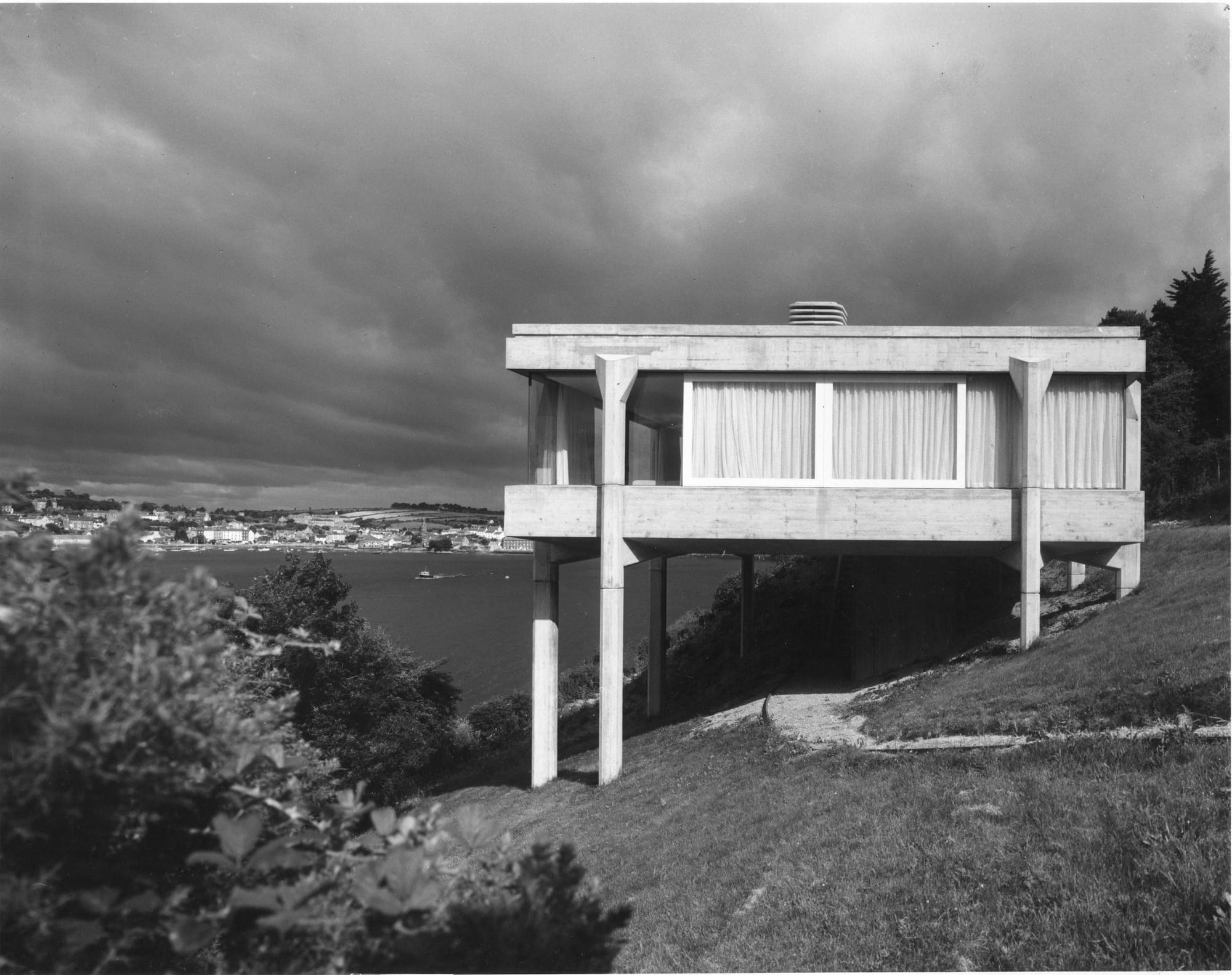

We get to see the Walker family’s vacation home, Bótharbuí (Irish for ‘yellow road’), on the stunning Beara Peninsula in Cork.

The site is made up of six man-made structures, three of which have been part of the hill for hundreds of years. In the early 1970s, Robin designed and built three new buildings to compliment the old cottages.

The home served as the Walkers’ summer refuge and is still owned by the family. Although the new structures are meant to reflect and be part of their natural surroundings, I can’t help but see them as apart from the nature they are slightly perched above.

Some of Robin Walker’s work has been modified from its original design, much to the vexation of his son.

Take the Restaurant Building at UCD. It’s one of Walker’s grandest creations, and originally had a completely open-floor plan. Simon explains the idealism behind the design, saying it was meant to give students freedom to interact and share ideas.

In the film, Simon visits UCD to see the building. He laments the closing of the open plan and wonders whether such a plan offered too much freedom of thought to the students for the institution’s liking.

But some might see it another way. Just looking at pictures of the original open-floor plan, I instinctively search for an alcove to retreat to. For some, perhaps the more introverted, I imagine the openness would be uncomfortable, not because of how free their thoughts were, but because of the feeling of exposure and overstimulation.

Whatever your opinion of modern architecture, Sé Merry Doyle’s film is a well-shot slice of family and architectural history.

Cinematographer Patrick Jordan puts you into the on-screen conversations, slowly panning from one speaker to the next.

Simon’s narration seems genuine and heartfelt, although something about his relationship with his father seems strange, as if the only way they could truly connect was through architecture.

After the film, I sat in the Irish Film Institute’s lovely glass-roofed courtyard in Temple Bar – a relic from the messy and human-scaled eighteenth century Dublin, the kind the modernist sought to tear down in favor of well-ordered concrete towers.

You can’t blame Simon Walker for feeling that modernist buildings are now the ones under attack; after all, the last of the Ballymun towers is being demolished. The lease on the old Bord Failte headquarters on Baggot Street was purchased by Irish Life and it may be knocked down and redeveloped.

But while the film touches on aesthetic critiques of modernist architecture, it would have been good to see it also tackle some of the complaints that have been raised by notable urbanists like Jane Jacobs and Jan Gehl, about how modern architecture affects urban life.

It is clear that Simon still believes in the ideals of modern architecture, and hopes to defend his father’s built legacy. He makes it clear that, in his view, the Baggot Street building should stay.

But even after the movie, I’m not sure I’m convinced of the Baggot Street building’s merits. Don’t listen to me, though. Go see the movie, and decide for yourself whether this man’s legacy is worthy of preservation.