What’s the best way to tell area residents about plans for a new asylum shelter nearby?

The government should tell communities directly about plans for new asylum shelters, some activists and politicians say.

As the climate changes, the city is set to experience more heatwaves, and the council should do more to prepare for them, say the researchers.

“It’s just very warm,” says Jennifer McCarthy, leaning on the brick wall outside her house on Drumalee Park, one hand on her bump.

“And I’m seven months pregnant, so it’s a nightmare,” she says. “And trying to keep three kids entertained, and a dog.”

McCarthy brings her kids out to play on the green near her house, she says, but there’s only one tree to stand under – not enough. “Standing under the tree while they’re playing is great. It’s shade.”

Christine Dunne, who lives around the corner on Drumalee Road, says she has found it very hot and feels fatigued so tries not to go outside. “I already suffer from high blood pressure.”

This loop of streets sits on the border of Stoneybatter and Cabra, and on the roads and estates stretching to the north of here, residents are likely to be particularly vulnerable in future to heat stress, found researchers in a 2021 paper published in the academic journal Urban Climate.

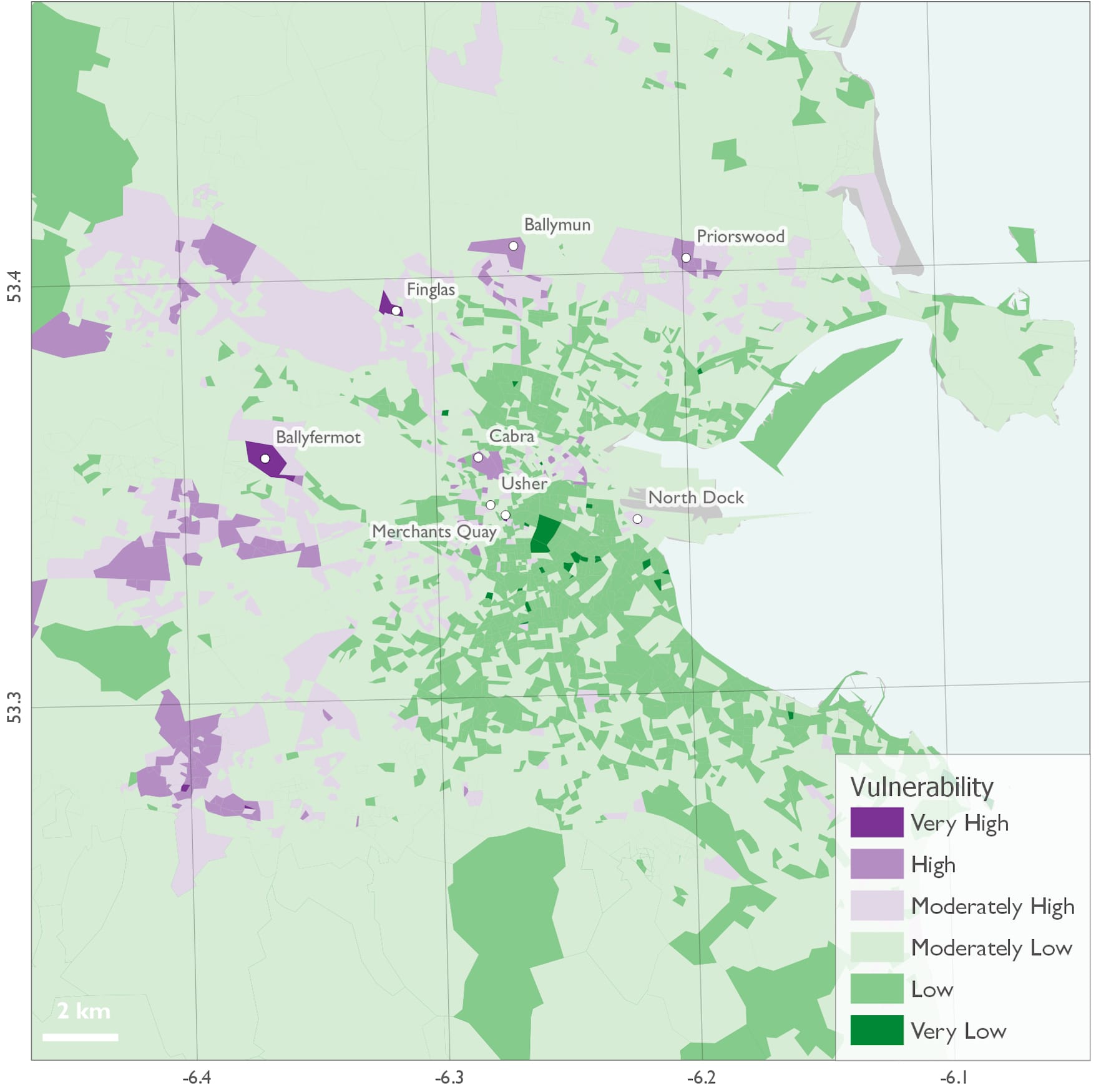

Researchers mapped areas of the city that will struggle when faced with increasing global temperatures due to climate change. Alongside Cabra, neighbourhoods such as Ballyfermot, Ballymun, Finglas, North Dock, Usher’s Quay and Merchant’s Quay would also likely be among the worst affected in the city, the map says.

This is because these areas have fewer tools available to them to handle the heat, says Roberta Paranunzio, a co-author and climate researcher for the National Research Council of Italy.

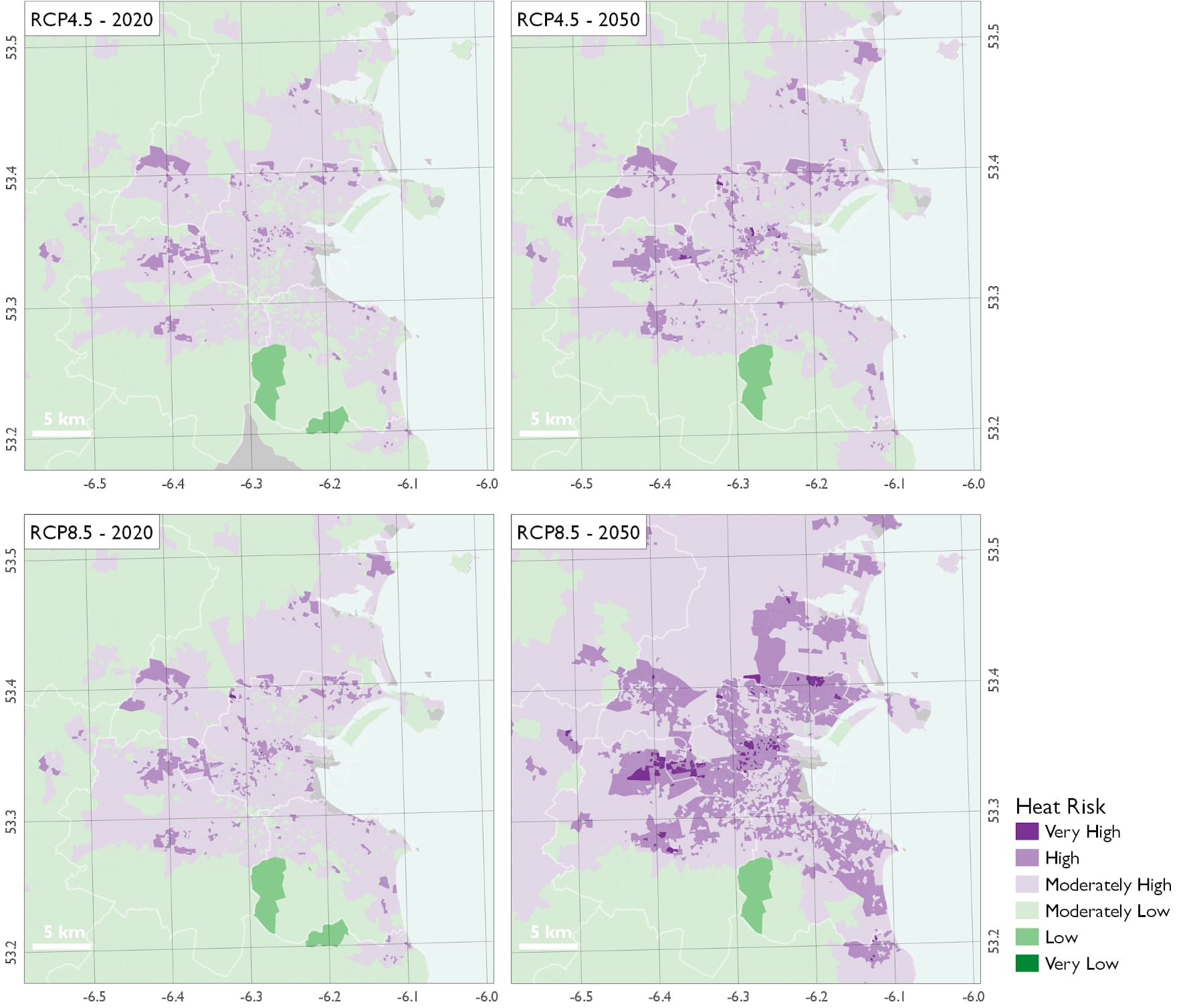

“The heat waves will be, this is in general, more extreme and more frequent in the future,” says Paranunzio, and areas that are already badly affected will only be worse affected. It’s important, she says, that the city plan for that.

On Monday, Met Éireann’s weather station in the Phoenix Park recorded a temperature of 33°C, the highest it has recorded since it opened in the early 1800s.

The eight hottest Junes on record globally all occurred in the last eight years, said a Met Éireann spokesperson on Tuesday.

While there hasn’t yet been a heatwave in Dublin this year – a heatwave here is technically when the temperature is above 25°C for five consecutive days – we are likely to see more of them, say scientists.

Depending on global increases in temperature, there could be up to 15 heatwaves in Ireland between 2041 and 2060, says an Environmental Protection Agency report on climate projections.

Paranunzio says heatwaves in Ireland will be more frequent and they will lengthen.

They calculated how at risk an area was by looking at economic deprivation, vulnerabilities of residents, like age, education level or disabilities,alongside how high projected temperatures would be in that area, she says.

More deprived areas aren’t necessarily more at risk of heat stress, says Paranunzio, because the amount of greenery or concrete can make a difference. So the researchers had to look at the current temperatures in small areas around Dublin, and apply projections to look into the future.

Ned Dwyer, a climate researcher and co-author of the paper, says heat feels worse inside densely built-up areas of a city. “All that concrete is causing more heat to be retained, at night, and then that’s radiated during the day.”

Humidity levels and lack of wind can also affect it, he says. “And we have the direct radiation of the sun.”

This causes what is known as an “urban heat island” effect, where people experience heatwaves more intensely because heat gets locked into tarmac and concrete, says Dwyer.

Inside the city won’t be added to as much as the outskirts will be, says Paranunzio. “If you increase your buildings, your roads, you are potentially expanding the area where you have this urban heat island effect.”

In their paper, the researchers looked into how much new building there would likely be, to see what areas would become more vulnerable as the city expands, and whether the number of vulnerable areas would increase, says Paranunzio.

“It could make the heat risk worse, because if the city is expanding you’re having more paved areas, more impacted surfaces. So this has an effect on the increase of temperature inside the city,” she says. “It makes those at risk, even more at risk.”

Dwyer says more development without interventions against heat island effect will mean more areas of the city that are vulnerable to heat.

Ireland does have a mild climate if you consider continental Europe, says James Fitton, an earth scientist and research fellow at University College Cork, and co-author of the paper.

But that doesn’t mean we can’t get extreme heat, he says. “Those high temperatures that we see now that, you know, are considered extreme, rare events, they’re eventually going to become more regular events in the future.”

Paranunzio says that since we are so used to mild weather, we’re less able to handle the risks of extreme heat. “Maybe people haven’t already understood this, I think.”

The infrastructure is built for milder climates and won’t be able to cope with the heat, she says.

Dwyer says that delaying measures for adapting to heatwaves could have a knock-on impact on other climate-adaptation measures, and the environment too.

People jump into their cars or pack onto public transport, flocking to parks, mountains, and beaches, to escape the urban heat island effect, he says.

They leave litter, he says, or worse, cigarette butts and barbecues that could cause wildfires.

But if the city is more comfortable during the heat, there’s less pressure on all those, says Dwyer. “There’s less pressure on transport infrastructure, less pressure on current green areas.”

Those who can’t afford to escape or ease their suffering during heatwaves are hit hardest though, says Fitton.

If you’re in poverty or on a low income, you likely can’t fix up your home to prepare for a heatwave, he says. “You can’t install air conditioning in the place where you live and it’s expensive to run.”

Health services should do wider education campaigns for what to do during heat, Fitton says.

“Staying out of the heat, staying hydrated, going to parks and respite areas, making populations aware of the impact of heat,” he says.

McCarthy, outside on Drumalee Park, says people don’t know how to stay hydrated during hot weather. “This is all new to us. Global warming, it’s out the window.”

Noel Nooney, who lives nearby on Drumalee Road, says he’s found the heat intense, too. “This is serious stuff. We’re not used to this.”

Bigger goals too are in play. Areas where there is already poverty and vulnerability are where people will suffer the most from heat, says Fitton.

“If we can already start reducing poverty, reducing vulnerability of people, increasing retention in education, and so on, we’re automatically helping people deal better with heat,” he said.

Reducing the urban heat island effect in these areas is important too, says Paranunzio, the co-author of the paper, so that people don’t, in their attempts to adapt to heat, end up increasing emissions –like by running air conditioners.

“It’s very tricky to take actions that are making people adapt, but also not worsening the climate,” she says.

Dwyer says the electricity for necessary air conditioning should come from green sources. All new buildings should be built with cooling capabilities from green sources, he says, and new developments should leave space for green areas and trees.

Current buildings should be retrofitted with better insulation to withstand both heat and cold, he says. Canopies on the outside of houses and shutters over windows are simple but effective.

The council can do this when retrofitting its own housing, he says. “What they need to do is take into account the fact that there will be heatwaves in future.”

Parks need fountains and water features, he says. “It’s refreshing, it’s cooling and it increases the moisture in the air locally.”

Fitton says outdoor swimming pools are a good solution, too. “It’s a recreational activity, tourism activity, but then, during an event such as a heatwave, then it offers another function, which is for health and wellbeing.”

Dwyer says people should have access to areas of reprieve close to where they live, like a park full of trees, a water feature, or cool indoor areas, to escape a house with poor insulation.

People can also build community there, he says. “If you can kind of bring people together, they’re having a social encounter, and isolation is one of the vulnerabilities related to heat.”

Nooney, on Drumalee Road, says the Phoenix Park and the green space on the Grangegorman campus are too far from them, and there are areas that could have a lot more greenery.

He points along the road, at the wide footpath. There are a couple of trees, but he imagines it could look a lot greener.

“That’s kind of a wasteland,” he says. “Trees, nice and cool. A lot of trees along there would be great. It’d just cover, it would cover the sun coming in.”

The green at the end of Drumalee Road, where McCarthy brings her kids to play, could have a lot more trees, says Nooney. “And maybe a water pond in there.”

Ebbie-Ann, a kid standing next to him, says it would be fun if there were water sprinklers to run through. “A waterfall!” she says, gasping to mime how hot the weather has been.

There should be water fountains, says McCarthy. “It would be nice to have something here, for the kids like. Another park.”

In December 2018, Paranunzio spoke at a workshop with the council at the Axis Arts Centre in Ballymun.

She presented her research on urban heatwaves, alongside other researchers working on flooding, coastal erosion and water quality, she said.

Council officials seemed more worried about those other problems than urban heat, she says, but she tried to make them sit up.

“I tried to make them aware of the fact that, maybe this is not as urgent now, but it will be urgent, if we don’t take action to mitigate and to adapt,” she says.

Dublin City Council’s Climate Change Action Plan notes that increases in temperature will put stress on buildings and transport, on waste management and on biodiversity, and that the most vulnerable populations are particularly at risk.

But it ranks heatwaves as the least likely and consequential risk, compared to increases in dry spells, cold snaps, extreme rainfall and wind speeds.

Paranunzio says urban heat will get more attention in the future, but we need to start responding now. “We will see the impacts not right now but maybe in the next decade,” she says.

Local councils should go further than their recent research to identify and prioritise areas that are the most vulnerable to heat, says Dwyer. “I’d say they need to take this report as a starting point, but then obviously build on it.”

“The interventions only need to come after they really kind of have pinned down what the other most vulnerable areas would be, and kind of what levels of heat stress we’re expecting,” he says.

Council officials should be thinking of life in the year 2100 when implementing infrastructure now, he says. “Babies being born today are still going to be here in 2100.”

“The buildings and the infrastructure we leave them needs to be able to deal with the upcoming climate challenges,” he said, “which include heat.”

Get our latest headlines in one of them, and recommendations for things to do in Dublin in the other.