What’s the best way to tell area residents about plans for a new asylum shelter nearby?

The government should tell communities directly about plans for new asylum shelters, some activists and politicians say.

It’s taken eight years for Sam Coll’s verbose debut novel to be published.

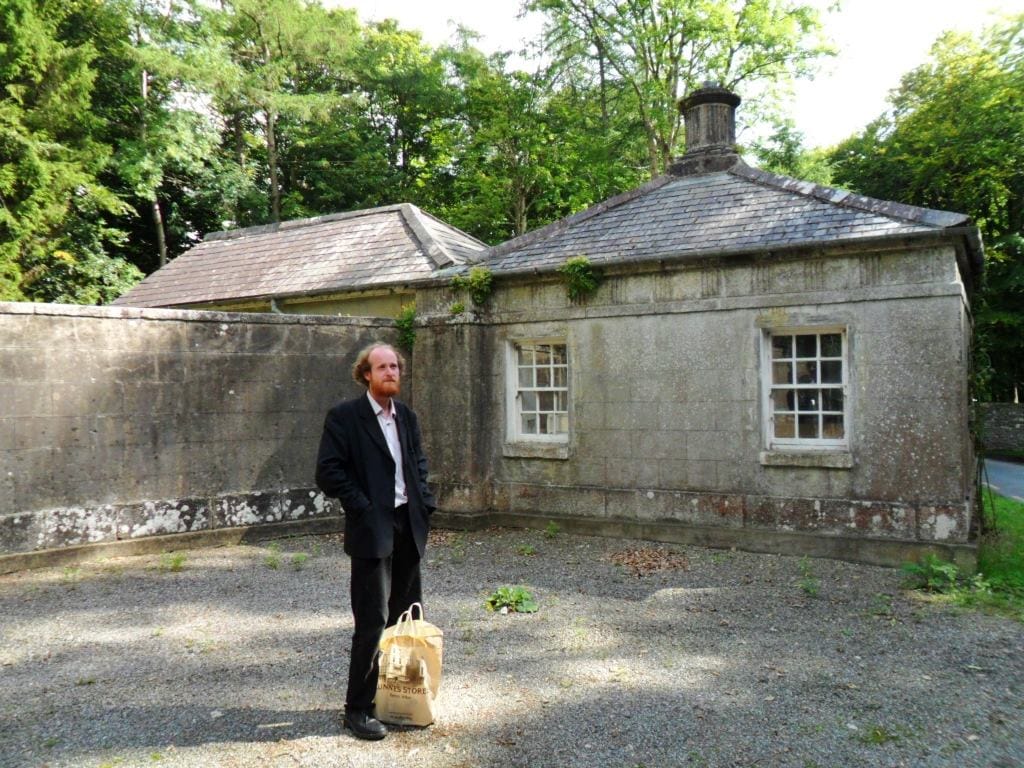

There’s a small cottage in County Kildare, which, in 2014, was home to Sam Coll, who at that time had been contracted to deliver his as-yet unpublished second book.

Coll’s agent and editor, Dan Caffrey, had arranged for him to be a live-in caretaker, keeping the place neat and tidy for the absentee owners.

This time alone would enable Coll to strike a number of titles from his list of The Classics he had always meant to read, and to complete, he says, roughly 65 percent of his thus far 100-chapter second novelistic effort.

“Thirteen months, with forays into the city on weekends … it was brilliant. It was the solitude, it was the monastic sanctum that you needed, like,” he says, sat in the smoking area of The Barge pub, by the Grand Canal.

Coll is stately, bald and bearded. It’s not that cold outside, but he wears a lot of layers: an old blazer over a zip-up jacket, over a button-down shirt. Some say his aesthetic is that of someone from a James Joyce work, were it set today.

“In retrospect it was the happiest I’ve ever been … The only regular human contact was the gardener, who would come every two weeks to deliver the post and clip the hedges,” he says. “He had a great phrase … ‘Don’t be workin’ too hard!’”

If chance had it that the gardener ever saw Coll’s body of work, he might reasonably think it the oeuvre of a man who had indeed worked too hard, or at least a hell of a lot.

At 27, Coll has produced the guts of two lengthy novels, a 1,000 page hand-written comic book, and numerous short stories – including a re-imagining of Joyce’s ‘Grace’ that was included in the book Dubliners 100.

Also included in his prolific output is Coll’s debut novel, The Abode of Fancy, which was launched in the Workman’s Club last Thursday, and published by Lilliput Press. It was written almost eight years ago, during his time as an undergrad in Trinity College Dublin.

“I would test out chapters on literary society there, and if they went down well they would stay in,” he says.

He gained a reputation as a good reader of his own work, but started to see that as a bit of a poisoned chalice, unsure if they were praising the reading or the writing. “I mean you can make anything sound good can’t you? Charles Laughton is on YouTube and he reads the telephone directory and makes it sound good,” he says.

Once a chapter had gone down well at Lit Soc, a cautious Coll would proceed to send it to friends in the hope that they’d make suggestions and edits. “There were some poor friends I used to bombard with chapters all the time,” he says. “They come to dread the email attachment.”

People who have read the long-awaited finished product don’t seem traumatised. It’s getting rave reviews.

The book’s jacket contains an impressive list of endorsements, including a quote from the British novelist Jon McGregor, who has twice been longlisted for the Man Booker prize, calling it “a work of cantankerous and bloody-minded genius, bursting at the seams”.

The Irish Times has called it “a hugely impressive linguistic feat”.

Coll says he doesn’t know how to gauge the public’s reaction to the book so far. “People who’ve read it recently say it reminds them of James Stephens and Sile De Valera. Sile De Valera! Sile De Valera! I’ve never read her, but it’s startling.”

Coll has created a work containing a cross-section of Irish literary influences: characters names – Arsene, Watt – are borrowed from Samuel Beckett, while the landscape of the story, with recognisable landmarks from Dublin and elsewhere in Ireland, is reminiscent of Joyce. His speech and use of language remind me of Jonathan Swift.

“When I first started it was a direct rip-off of Ulysses,” he says, wincing into his pint of Guinness. “It was set over one single day, December 3rd, 2007. I mean that had to go out the window, that was so blatant a steal. In fact I don’t think it’s influenced enough by Ulysses, frankly. I mean, Ulysses is forward-thinking and innovative.”

“It’s a 19th century novel, except with gimmick of being set in 2008. I mean there’s very archaic diction and whatnot and blah, blah, blah.”

Now, in its current form, the book is more like At Swim-Two-Birds by Flann O’Brien than anything by Joyce: there are texts within the text, a framing story, and a number of mischievous characters from folklore interacting with ordinary people.

Coll is, at times, self-deprecating. He says that while he is proud of the book, it now feels alien to him, having been written at such a young age. “I had the audacity of ignorance then, and I probably couldn’t do it now,” he says. “Which is either a regression or an advance, I don’t know.”

And indeed, the book bears the marks of its sophomoric origins. Much of The Abode of Fancy is concerned with the vicissitudes of 18-year-old Trinity student Simeon Collins, who has a series of heartbreaks and unrequited loves at the expense of a number of young women.

The story of Simeon’s loves intersects with another narrative, that of a supernatural character called The Mad Monk, who has returned to Ireland to find his brother, Elijah. Meanwhile, the poet Tadgh O’Mara is travelling across Ireland to find his daughter.

Simeon – from whose perspective much of the book is written – has a chivalric, quixotic conception of what love in is, having only read and seen romance in film. His love interests are coloured by the perspective of an uninitiated adolescent.

As the narrator tells us in the book: “This concept, of ‘going out’ with someone, was a foreign one to Simeon, who was schooled in the outdated traditions of a bygone age, who took as his chivalric model the nutty Knight of La Mancha. He thought love involved nothing more than loving, and impassioned protestations of that love to the beloved, who might initially quail and swoon to hear such potty pleasantry, thereafter come round and consent. But little use proved to be the quixotic designs of the Don for his Dulche, no, not here, not now.”

I ask Coll about the women in the book, and the character Saruko, the first in a series of Simeon’s unrequited loves.

“She’s deliberately meant to be one dimensional. That’s why she’s the first love,” he says. “She’s a reflection of … it’s more about the idea of being in love. I read this in Death in Venice today, something like, ‘The true God is not the lover, it’s the beloved,’ or something like that. You aren’t meant to know much about her. He [Simeon] is full of all this stuff that just dissolves in daylight, but matters in the moment.”

I ask Coll what made him want to write about unrequited love, in particular that of a young man.

“Well, having it,” he says. “… It’s a very juvenile thing, ‘Oh boo-hoo, she doesn’t love me but I love her.’ You want to shake the guy and make him snap out of it. But it’s still a very powerful emotion and a lot of people can identify with it at some point in their lives … whole lives can be lived out under its shadow, God knows.”

The characters – whether Simeon Collins or mythical beings like The Mad Monk and Arsene Elijah – inhabit a literary universe Coll has created. Personalities from other works of his are included in The Abode of Fancy, and vice versa.

The Mad Monk, is, as Coll puts it “a refugee from another work”, his 1,000 page comic, which tells the tale of his “dying and rising again”.

“The Abode of Fancy got its necessary infusion of fantasy from it [the comic],” he says, of the book’s numerous narratives.

“I’m inclined to think that the comic book is the best thing I’ve done, because it’s the purest, pen on paper from start to finish. The problem is the dialogue started to outweigh the pictures because the speech balloons would be that big, and the characters would be squashed into the bottom of the frame.”

The Abode of Fancy features a section called “The Mad Monk’s Doggerel Epic History” that is, Coll says, “an attempt to condense into 15 pages, the entire 1,000-page odyssey he came from before”.

“He’s got a pre-history,” he continues. “And that’s the thing – if this book gets sufficient attention, I’ll be in a position where I can put that comic book out there, on the net, a page a day or something like that.”

Sometimes, he thinks in pictures, he says. “I know exactly what he [The Mad Monk] looks like, and it bugs me if people are going to illustrate him any other way.”

In addition to being an author, Coll is also an actor. He was part of The Spoonlight Theatre Company during his time in Trinity, which included a run of Heartbreak House in 2012 for the Ten Days in Dublin festival.

He insists he’s not much of an actor. (Friends say different.) “I’m not trained, that’s the problem, I’m a copycat. I’ve watched actors, and it shows,” he says.

Coll’s use of old-fashioned diction, it turns out, is accompanied by a love of actors from bygone eras. “I love watching dead actors,” he says. “Richard Burton doing Under Milkwood, that’s a great one. Eh, what else? Rime of the Ancient Mariner is a fine one … Paul Scofield as King Lear!”

He goes on, telling me about a role he had in a film. “I also had a big part in this Donal Foreman film, Out of Here,” he says. “That got premiered in Galway, it was in the IFI … ”

It was good fun, he said. “My involvement was pretty limited. I was originally considered for a bigger part and I did a screen test for it, and I think I must have cracked the lens because they then rewrote a scene based on what he knew about me to make it more suited or something.”

“I went from playing a maladjusted misfit in a raincoat to being this drunk in an alley. Haha! Probably more fitting, the latter.”

Given that he’s an actor himself, and that he seems particular about depictions of his own characters, I ask Coll who he would like to see play them – if anyone – were his book ever to be made into a film. He lists an all-star cast of dead, or elderly thespians.

“Albert Finney for Albert Potter … Michael Gambon for Arsene O’Colla … John Houston or Christopher Lee for The Mad Monk, either or … , Ralph Richardson for Elijah, who doesn’t appear very much, but becomes Arsene Elijah towards the end.”

“And that’s weird, because you’d have this happy amalgam of Michael Gambon meshed with Ralph Richardson. You’d have Ralph Gambon; you’d have Michael Richardson!”

Throughout the chat, Coll’s answers indicate how his mind entangles ideas and characters from disparate environments and backgrounds. His creations, including The Abode of Fancy, are a kind of mash-up of the canon of Irish literature, theatre, and film.

But I still can’t tell if he’s joking or not when he says his book is “Flann O’Brien for the Inbetweeners crowd”.

The Abode of Fancy, Coll says, started as an exercise to learn how to write. The book is linguistically adventurous, filled with delightful quips and turns of phrase, inventive descriptions of places and people.

In one scene, The Mad Monk tries to help a lovesick hare win the affections of a female hare he has long admired from afar.

“Ah . . . yes. Love. Sweetest of dreams, our life’s bitterest mystery, our foremost misery. I know the feeling well, old as I am, and have felt so oft in my time its prick and sting, its brief and intermittent bliss that will so swiftly turn to rancour, that yet will come again to be a craving for sating, wringing our anguished hearts until we can take no more – though forever always we eternally do come back for more.”

Coll wasn’t thinking about publishing the book at first. “For years it was for myself, because no one would ever see these things, but eventually, I dunno, you feel an exhibitionist urge where you want to share things,” he says.

But then he met Colm Tóibín by chance and that all changed.

“I told Colm Tóibín, when he visited our Lit Soc in 2009, that I was working on the novel as a kind of exercise to teach myself how to write, and he said, ‘Don’t bother with exercises, write for publication.’ So I did.”

Once Tóibín gave Coll the kick he needed, he completed the novel. After that, it spent years floating around as an email attachment, until, eventually, it landed on the desk of Dan Caffrey of Lilliput Press, who became its editor.

“He liked it a lot, but this was also a disadvantage because he didn’t know what to cut or where to be ruthless,” says Coll. “He used to say things like that it was 80 percent perfect, which has demonstrably proved to not be the case, but he gave his edits to me and I worked on them.”

Around 2013, a white-covered, 616-page version of the book was printed by Lilliput and put into circulation. The hope was to snag a US or UK publisher, but when that didn’t happen, Lilliput decided to run with the book itself.

“It looked like the white album. That was good, there were about 100 copies of that. It got bandied around to places in London and in the US. And it had an impressive roster of rejections,” says Coll.

“A lot of them were like regretful rejections, ‘I like this a lot but I don’t know how to market it. ‘You should chop it into two books.’ And there was no consensus either. Nobody knew, I mean everybody liked the different bits, which I took as a great compliment. Nobody could decide what was wrong with it or what was right with it.”

Eventually, our conversation turns to the verity of the events and characters depicted in the book. I ask Coll how much of him is in the characters.

“Quite a bit I dare say. But the whole thing feels very posthumous because it was so long ago.” he says.

He shares the initials of the book’s protagonist, and in some ways they bear a striking resemblance to each other. “That’s to throw people off the track!” he says. “David Foster Wallace has done that trick before. In The Pale King, there are several characters called David Wallace aren’t there?”

“… Simeon – and that’s good because it’s a pun on apelikeness – insofar as he’s me, fine, he’s my worst aspects,” he continues. “My most apelike, beastial parts. Get all that out. In that sense, he’s a self-portrait, but it’s not a complete portrait. He’s a facet.”

He goes on. “It’s a composite. I mean maybe this character is based on that person and this background, but what they say bears nothing, no relation to what they’re like in real life because that’s based on somebody entirely different, if it’s based on anyone at all. I mean it’s drawn out of the head.”

The text consistently invites the reader to imagine the author as its protagonist. At one point, Simeon decides to write a novel containing his friends, vowing to include them, warts and all, in his Great Work.

“Everyone he knew was in it, their names unchanged, their foibles and faults held up for scorn and ridicule, their virtues venerated, their quirks revered, yes, all, all of them would be given their space to shine and their page to prance, he would pull their strings and make them talk and walk, like a demented crackpot deity,” it reads.

I get the impression that the posthumous feeling Coll describes has removed him to a healthy distance from his character, whose true autobiographical extent it is difficult to gauge.

“I don’t identify with that little shit at all,” says Coll. “That little shithead, SJC, no, no, no, I want to see him squashed out of sight, frankly, Simeon, that is. He’s like a lot of young men at that age are.”

At one point, Simeon decides to immortalise his college chums in “the great Trinity novel”.

“I mean the thing mutated, alright?” says Coll. “When I started it, everybody I knew was in it, but gradually you start to mesh them together and then you put this conglomerate on the single label, the single name of say ‘Albert’, or the single label of ‘Jezzie’.”

While the book consistently invites the reader to imagine that it is autobiographical, it does so in a sardonic and self-aware fashion, taking deliberate indulgences to let the reader know that the author is aware of the potential pitfalls and accusations someone who did such a thing would face.

This is what such an 18-year-old, equipped with the audacity of ignorance, who was writing a biographical account of their friends would write, right? How else could you account for a scene in which, for instance, a character looks at young Simeon Collins’ genitalia and remarks, “Ooh it’s so big”?

“The problem is,” says Coll, “I knew that I was perpetrating a trap. There are far too many novels about young men finding themselves and all this crap.”

“In a lot of ways I’m nothing like that character, really,” says Sean Fitzgerald, who is a friend of Coll’s, and spent a lot of time with him while he was writing The Abode of Fancy. “But I think he based it on me. Well, I know he based it on me.”

I meet Fitzgerald in his house in the city, a few hours before he is due to go to the official launch of The Abode of Fancy. We stand with tea beside a piano.

He doesn’t seem bothered that he, or a shadow of him, features. “It’s grand, ya know?” he says. “… People want to read about bad, stupid kids.”

A scene, describing the relationship between Simeon and his friend Johnny Fritzl – who bears a conspicuous resemblance to Fitzgerald – reads:

“For Fritzl was the sweetest of them, fluffy of head and beard, and warm of heart and soul, possessed, on first appearance, of a ferocious pride I initially abhorred and mistook as arrogance, since he was given impulsively to hate the primary impressions he obtained of a new person, a stranger to his ways, until, in time, after a sufficient period had passed in which he cocked his head, and studied one’s moves with a panther’s gaze, and figured one through like a botanist, he grew at last to like what he saw, and then to befriend and love – and truly no man could be worthy of so intense an affection as Johnny Fritzl bore for me.”

Fitzgerald can recognise the representations in the book. “I think it’s more like, these are glaringly inaccurate depictions of people that I knew when I was 18, and now I still know these people and my perception is a little different, so therefore now they are fiction,” he says. “The past is a foreign country, we’re all strangers, that kind of thing.”

I tell Fitzgerald about Coll’s quip that his book is “Flann O’Brien for the Inbetweeners crowd”.

“Yeah, that’s typical,” he says. “He doesn’t actually want to do that. It’s just the idea of being that is funny. It’s tongue-in-cheek, it’s satirical at heart … I think he’s like an apocryphal Irish literary figure – he’s like that but then he’s completely different, because it’s like a satire of the idea of even being that figure.”

“Even the name The Abode of Fancy,” he says, “is really funny. We were all laughing about it. It’s such a great joke, what a ridiculous name. Youth y’know? It’s an abode of fancy.”

Perhaps, even the supernatural element has some echo with reality, says Fitzgerald. “In some ways, I think it probably is really accurate,” he says. “Because it was a supernatural time. Youth is kind of supernatural, because death seems such an alien.”

For him, the book is about a lot. “I’d say it’s about loneliness, it’s about friendship, it’s about death and life and youth and aging, it’s about everything.”

“I’m curious to see,” he adds, “are people going to read this book, and are they going to see their own world? It’s definitely a book with a lot of scope, that captures the lives of people … I think if younger similar characters to the characters in this book read it, they might get something from it.”

At the launch, people are drinking and smoking and being merry. It’s a celebration. Upstairs in The Workman’s Club is jammed, and Coll wanders around, looking nervous yet relieved, trying to say hello to everyone.

There are the official launch speeches, from Caffrey and also from Gavin Corbett, author of Green Glowing Skull and This Is the Way.

Finally, Coll steps up to read. Reminiscent of the actors he imagines playing his characters, his voice quivers and undulates.

He chooses a scene from the book in which The Mad Monk’s dog attacks another character, who is standing at W.B Yeats’ grave. “Nice doggy!” he says, toward its end, as the crowd erupts in laughter.

Coll steps down from behind the microphone and begins the night-long ritual of signing books, leaving his mark with his name scrawled alongside detailed cartoons of his characters.

Finally, after eight years, The Abode of Fancy is out.

Get our latest headlines in one of them, and recommendations for things to do in Dublin in the other.