What’s the best way to tell area residents about plans for a new asylum shelter nearby?

The government should tell communities directly about plans for new asylum shelters, some activists and politicians say.

Sandymount resident Joe McCarthy keeps asking the same question: three percent of what? He thinks the answer could be worth nearly €5 million.

Sandymount resident Joe McCarthy keeps asking the same question: three percent of what? He thinks the answer could be worth nearly €5 million.

As a condition of the planning permission for the giant waste-to-energy plant underway in Poolbeg, the folks behind the project – Dublin City Council and US waste giant Covanta – were told to create a community fund for local neighbourhoods. The money is likely to be spent on goodies like sports facilities, playgrounds, and community services for elderly people.

The start-up lump sum for the fund was set at three percent of the capital costs of the project, with later annual contributions. What McCarthy wants to know is how that three percent has been totted up, and what exactly “capital costs” means in this case.

Source: Dublin Waste-to-Energy Project

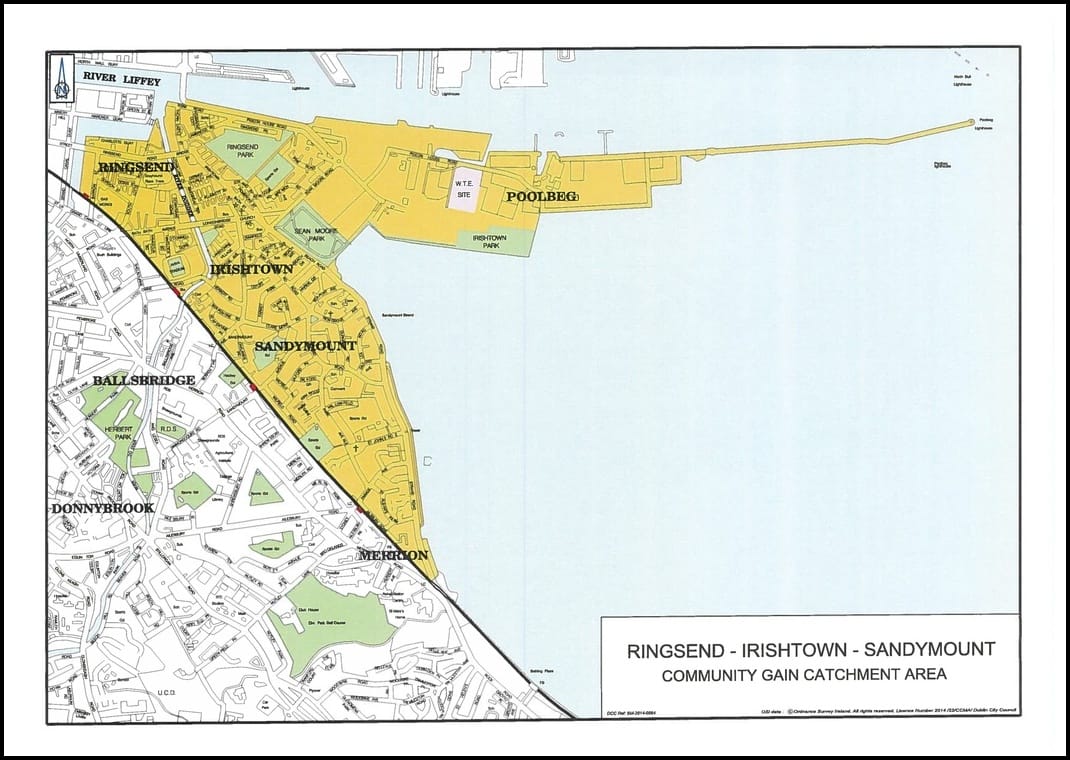

It all sounds dull. Until you realise that over the life of the power plant, millions of euros from this fund will pour into local communities found within a boomerang-shaped catchment area that runs from Ringsend in the north to the southern end of Sandymount, and might be affected by the plant.

And how that three percent is calculated will affect how many millions is spent on making the area a better place to live.

According to Dublin City Council and Covanta, the community fund will total €10.38 million. The capital costs, they say, are the construction costs, and the construction costs are €346 million. Take three percent of that, and you get your €10.38 million.

McCarthy doesn’t buy it though. He says he believes the figure should be closer to €15 million, which is three percent of €500 million. He’s cyber-rifled through Covanta’s company filings in the US and pinpointed that they say that: “The total investment in the construction of the facility will be approximately €500 million.”

McCarthy believes that some things that should be counted as capital costs have been excluded from that category. Which raises the question: what’s in and what’s out?

City Council Executive Manager Declan Wallace at the April meeting of the City Council’s environment committee, suggested that operating costs have been and should be excluded.

“As far as we are concerned, it is three percent of the construction costs, and I think that any reasonable person would think that three percent of the five-hundred million – which includes operating costs for the next number of years – would be probably somewhat punitive,” he said. “If he [McCarthy] isn’t happy with it, there are places where that can be remedied.”

At the same April meeting, McCarthy argued that Wallace had it wrong. “The monies published by Covanta do not include operating costs,” he said. “They only include capital costs of construction and financing. Operating costs are separate.”

Indeed, Covanta’s accounting for what makes up the difference between the €346 million and the €500 million did not mention operating costs.

“The non-construction project costs incurred by Covanta come from a variety of things, such as financing, advisor fees, and contributions to the Community Gain Fund itself,” said Covanta Director of Communications and Media Relations James Regan, in an email.

One of the problems here is, if you’re looking for a universally agreed definition of capital costs, it’s not too easy.

Basically, capital costs are costs that are treated as the creation of a long-term asset; they’re costs that provide benefits over many years. That much is clear.

Imagine for example, that you’re building a toll road. The cost of designing the toll road might be classed as an expense, building the toll road as a capital cost, and hiring people to staff and maintain the toll road as operating costs.

There’s a catch, though. Neither accountants nor tax authorities are consistent in their interpretations, especially when it comes to so-called “non-conventional” capital costs.

For example, pharmaceutical companies’ research and development expenses, which some would argue should be treated as capital costs, are often treated as operating expenses for accounting and tax purposes.

If what is treated as capital and what is an expense is often tweaked, it begs the question as to why the community gain fund was based on the capital costs, rather than, say, the total project cost.

An 28 May email to Declan Wallace via the City Council’s press office asked whether the City Council might change approach for future projects. The response didn’t address this question.

So far, Dublin City Council doesn’t seem to have done a whole lot to shed more light on the disagreement over what’s a capital cost and what’s not, to answer McCarthy’s questions.

But chair of the environment committee, Fine Gael Councillor Naoise O Muiri said last week that he’s waiting for a report in a couple of weeks time that he believes will set out clearly how the figure has been calculated.

Perhaps that will resolve McCarthy’s €4.62 million question.

Get our latest headlines in one of them, and recommendations for things to do in Dublin in the other.