What’s the best way to tell area residents about plans for a new asylum shelter nearby?

The government should tell communities directly about plans for new asylum shelters, some activists and politicians say.

It could also help smooth the way for the redevelopment of St Patrick’s Athletic FC’s home ground Richmond Park, which is next to the river.

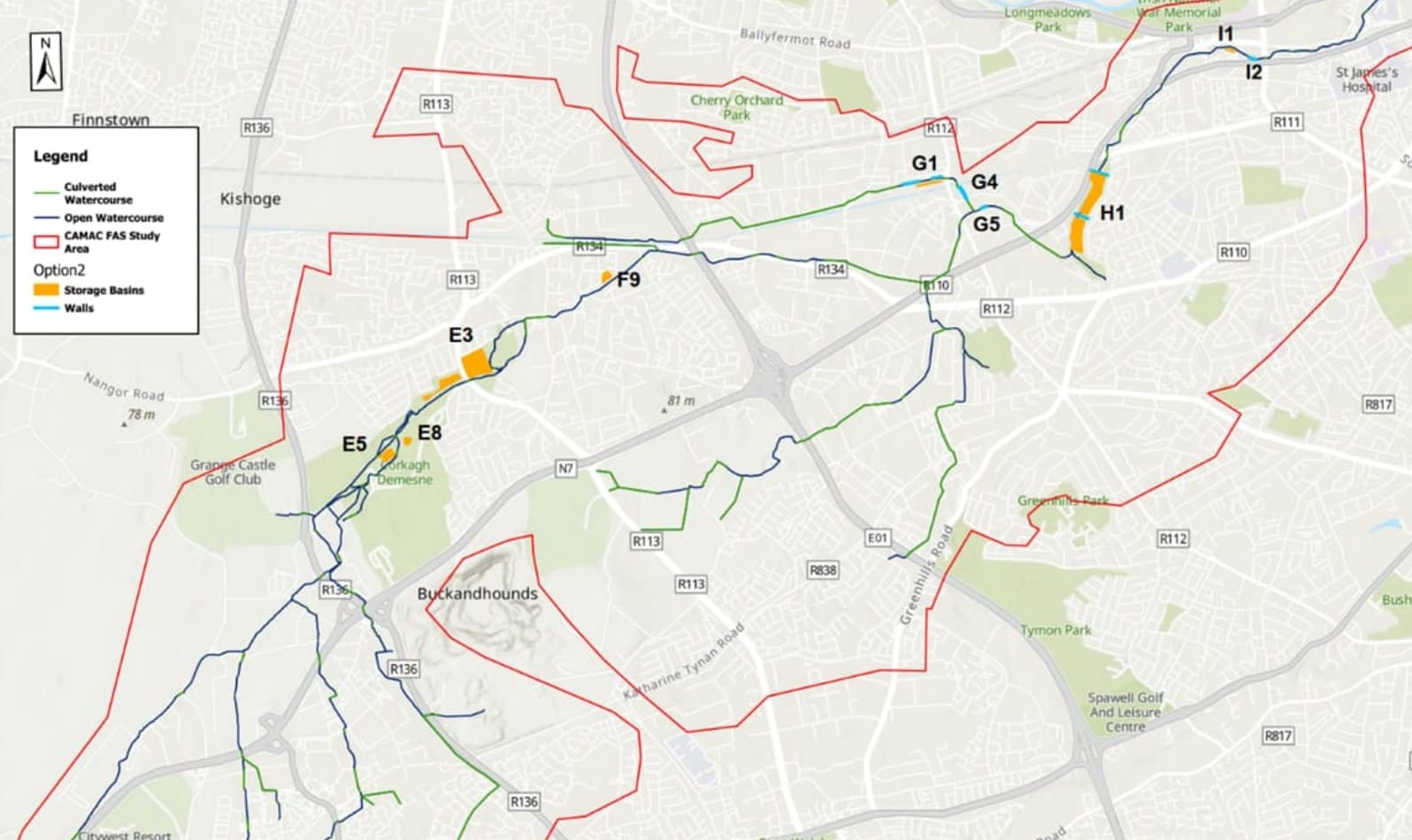

To protect homes and businesses along the Camac River from flooding after heavy rains, the two Dublin councils along it plan to build storage areas to hold big pools of rainwater – which can then drain down slowly through the river over time.

They’re also looking at installing floodwalls along a few stretches, said Gerard O’Connell, a senior engineer for Dublin City Council, at a meeting of that council’s South Central Area Committee on 17 April.

“We’re trying to get as wide a flood option as possible to protect as many properties,” O’Connell said, of the scheme – which also extends into South Dublin County Council’s area, to the south-west of the city.

The scheme could mean flood storage on Clondalkin’s Corkagh Park and Yellow Meadows, and also Drimnagh’s Lansdowne Valley Park. As well as flood walls in Ballyfermot’s Labre Park, Bluebell Avenue, Kilmainham’s Turvey Park, and Old Kilmainham, O’Connell said.

It could help smooth the way for the planned redevelopment of St Patrick’s Athletic FC’s Richmond Park in Inchicore, O’Connell said. And for a long-planned redevelopment of Labre Park in Ballyfermot, he said.

It will likely include a flood wall protecting homes between the river and Old Kilmainham, where Labour Councillor Darragh Moriarty says problems getting insurance have kept people from buying and selling.

And it will likely involve lowering the high wall on the north side of Goldenbridge, which carries Emmet Road over the Camac in Inchicore village, O’Connell said.

Two-thirds of the Camac and its tributaries are in South Dublin County Council’s area, and the rest are in Dublin City Council’s, O’Connell said.

The river flows down from a height of about 4oom west of the city, through Bluebell, Inchicore, and Kilmainham – emptying into the Liffey near Heuston Station, he said.

In 2011, it rose over its banks and flooded areas between the river and Old Kilmainham, including Lady’s Lane, Kearn’s Place, and Shannon Terrace, he said. “A number of people nearly lost their lives as well.”

With consultants, the councils did an array of topographical and bathymetric surveys, as well as using CCTV to peek into culverts the river runs through, O’Connell said.

The team used this information to build a model of how water flows through the Camac basin, including not only 55km of the river and its tributaries, but underground drainage from housing developments, O’Connell said.

They also did studies and reports on the environment and wildlife along the river, to take into account how they would be affected by flood defences.

Then they looked at a range of possible ways to reach the goal of protecting as many homes as possible from a 100-year flood event – a flood that statistically has a 1-percent chance of occurring in any given year.

The team found that 841 homes and 141 non-residential buildings in the Camac basin are at risk of being drenched by a 100-year flood, O’Connell said.

The modelling envisions a 20 percent increase in rainfall by the end of the century, due to climate change, O’Connell said. “We’ve had 7% in the last 30 years so 20% more by the end of the century doesn’t seem that unlikely,” he said.

Figuring in that additional rainfall, 1,352 homes and 200 non-residential buildings would be at risk of a 100-year flood, he said.

Flood defences have to be “cost-beneficial”, O’Connell told the committee.

“The cost of the scheme has to be less than the damages [it prevents] for approval from the funding body, which is the Office of Public Works,” he said.

The team couldn’t find a way to protect the whole basin from flooding where the benefits in terms of damages prevented would outweigh the construction costs, he said.

So they divided up the basin into a puzzle of pieces and tried to find cost-beneficial defences for as many as they could, he said.

“Option 1”, which “was found to be cost-beneficial”, includes three areas of water storage in Corkagh Park, one in Yellow Meadows, and two dams on the river in Lansdowne Valley Park – each 30 metres wide and 4 metres high, O’Connell said.

Each dam would have a channel through it to allow the river to flow at normal rates, but after big rains, they’d hold back excess flow and drain it down relatively slowly through that channel, he said.

“It’s existing football fields in Corkagh Park, or we would be excavating new storage areas which generally would be dry but during a 5-, 10-, 15-year flood would fill up with water and then slowly drain back into the main Camac,” he said.

“Option 2”, includes those same measures but also adds flood walls in Labre Park, Bluebell Avenue, Turvey Park, and Old Kilmainham. The costs and benefits balance for this option as well, O’Connell said.

“Option 3”, would add storage at Saggart Lakes, and flood walls at Ballymount Industrial Estate, Gallanstown, and Goldenbridge Industrial Estate. This would be cost-beneficial, but would cause flooding elsewhere, which the team is looking for ways to solve, O’Connell said.

The councils have been doing a round of public consultation on their plans so far. They plan to take the feedback they’ve gotten into account and develop an “emerging preferred option” within two months, O’Connell said.

Then there’s detailed design work and an environmental impact assessment to do, then a final report, an application for planning permission, a statutory public consultation – and, assuming planning permission is granted – then construction can begin, he said.

“We’re hoping to go to planning next year on this,” he said. “The Poddle [flood defence scheme] took four years to get planning. The average is about a year. And then the construction will probably take two to three years. So we’re a number of years away.”

The flood defences could help smooth the way for several projects which face flood risk, O’Connell said.

St Pat’s wants to expand Richmond Park, its home ground between Emmet Road and the Camac.

Labour Councillor Darragh Moriarty asked O’Connell whether he thought St Pat’s would have trouble getting planning permission for that, due to flood risks at the site.

Independent Councillor Vincent Jackson said, “Whatever we do we shouldn’t jeopardise the redevelopment of Richmond Park.”

O’Connell said he was in touch with St Pat’s about how the new flood studies and proposed flood defences would affect their project. “I would say the risk has reduced for that development,” he said.

Sinn Féin Councillor Daithí Doolan asked how the project would impact efforts to build homes around the long-vacant Black Horse Inn.

“We have been presented on a number of occasions with plans to develop the former Black Horse pub and the lands behind it, and that was knocked back on a number of occasions because of the flood risk to the properties there,” he said.

In 2018, Black Horse owner Tom Kelly applied for permission to build a multi-storey apartment block on the site, but was refused in part because of flood risk. But Alanna Homes took over the effort and managed in 2021 to get permission.

However, Michael Kelly hasn’t been able to get planning to build a terrace of 10 two- and three-storey homes behind the Black Horse between the Grand Canal and the Camac.

He applied to the council in 2022 and was refused the same year, as the land is zoned for green space – and is at risk of flooding – among other reasons. He appealed to An Bord Pleanála, which turned him down on 17 April 2024, also citing flood risk, among other reasons.

O’Connell said the proposed scheme would help defend this area from flooding. “The development near the Black Horse pub, the risk has probably reduced,” he said.

But that still leaves all the other reasons the council and planning board refused Kelly permission for the terraced homes.

Moriarty also asked whether the scheme would help homeowners and homebuyers along Old Kilmainham, an area hit by flooding in 2011.

“There’s difficulties there both with people trying to sell their homes because of the flood risk and also people trying to buy in that area because they can’t get mortgage protection because of the flood risk,” he said.

Option 2 includes installing a flood wall in Old Kilmainham to protect that area from high water.

Doolan and Right to Change Councillor Sophie Nicoullaud asked how the flood defences would affect Labre Park. Plans to redevelop part of that Traveller housing site have been held up for years, with officials citing concerns over flood risk.

O’Connell said the planned flood wall there should help alleviate that risk. “So that should be possible to develop that,” he said.

Could bits of the river that are now routed through underground culverts be brought back to the surface again and restored to a more natural state? asked Green Party Councillor Michael Pidgeon.

“Closer to Kilmainham there’s been conversations around de-culverting, trying to get away from it being just a concrete-encased river,” Pidgeon said. “Any plans or ways to undo some of that stuff?”

“Generally it means more flooding downstream,” O’Connell said. “Some of the tributaries alright, yes alright we can open up some of those.”

Last year a community group was campaigning for the council to lower the high wall on the north side of the Goldenbridge in Inchicore.

O’Connell said that’s on the cards as part of the Camac scheme. “The Goldenbridge, we’re hoping to take away some of the concrete wall there so people can see the river,” he said.

Get our latest headlines in one of them, and recommendations for things to do in Dublin in the other.