What’s the best way to tell area residents about plans for a new asylum shelter nearby?

The government should tell communities directly about plans for new asylum shelters, some activists and politicians say.

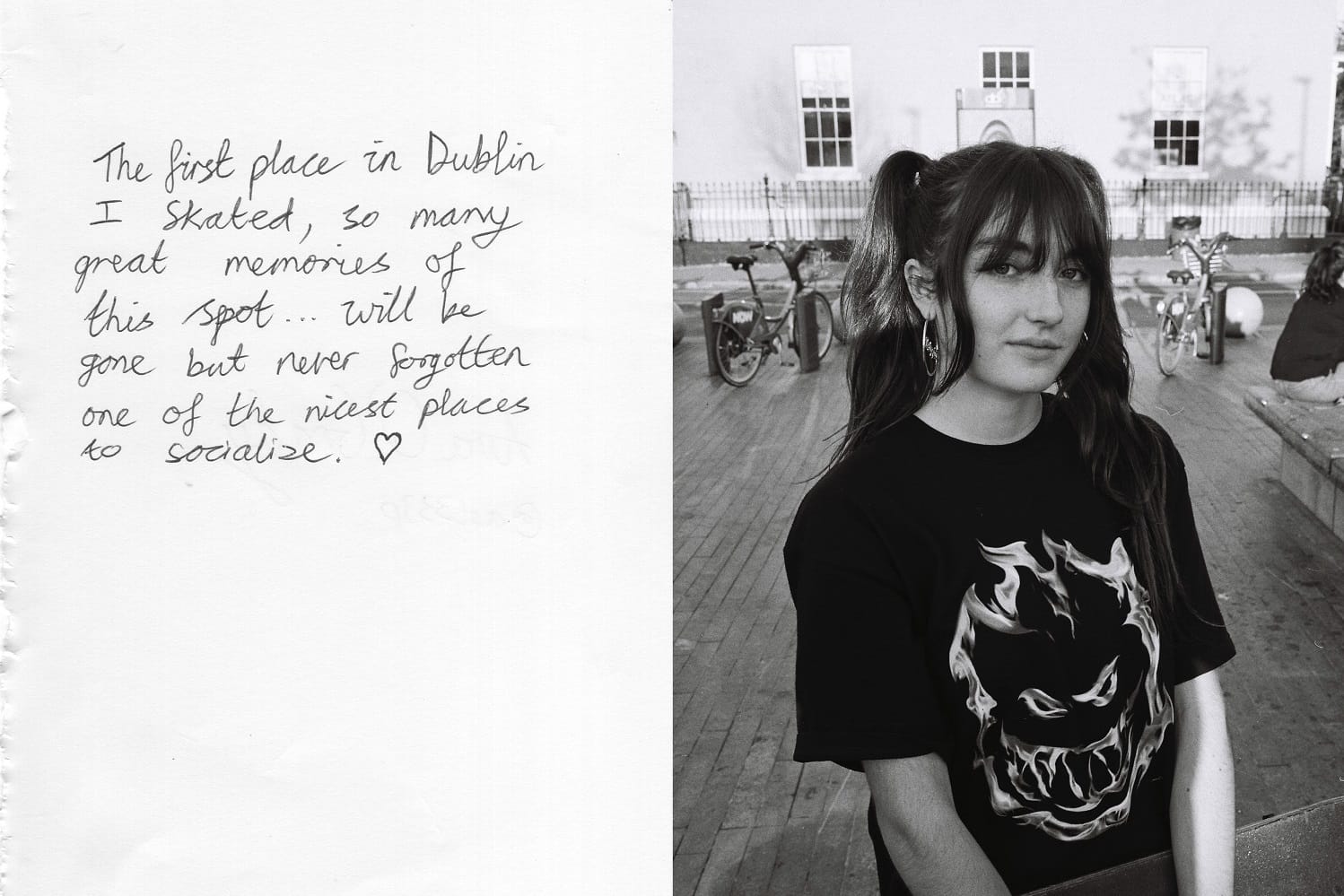

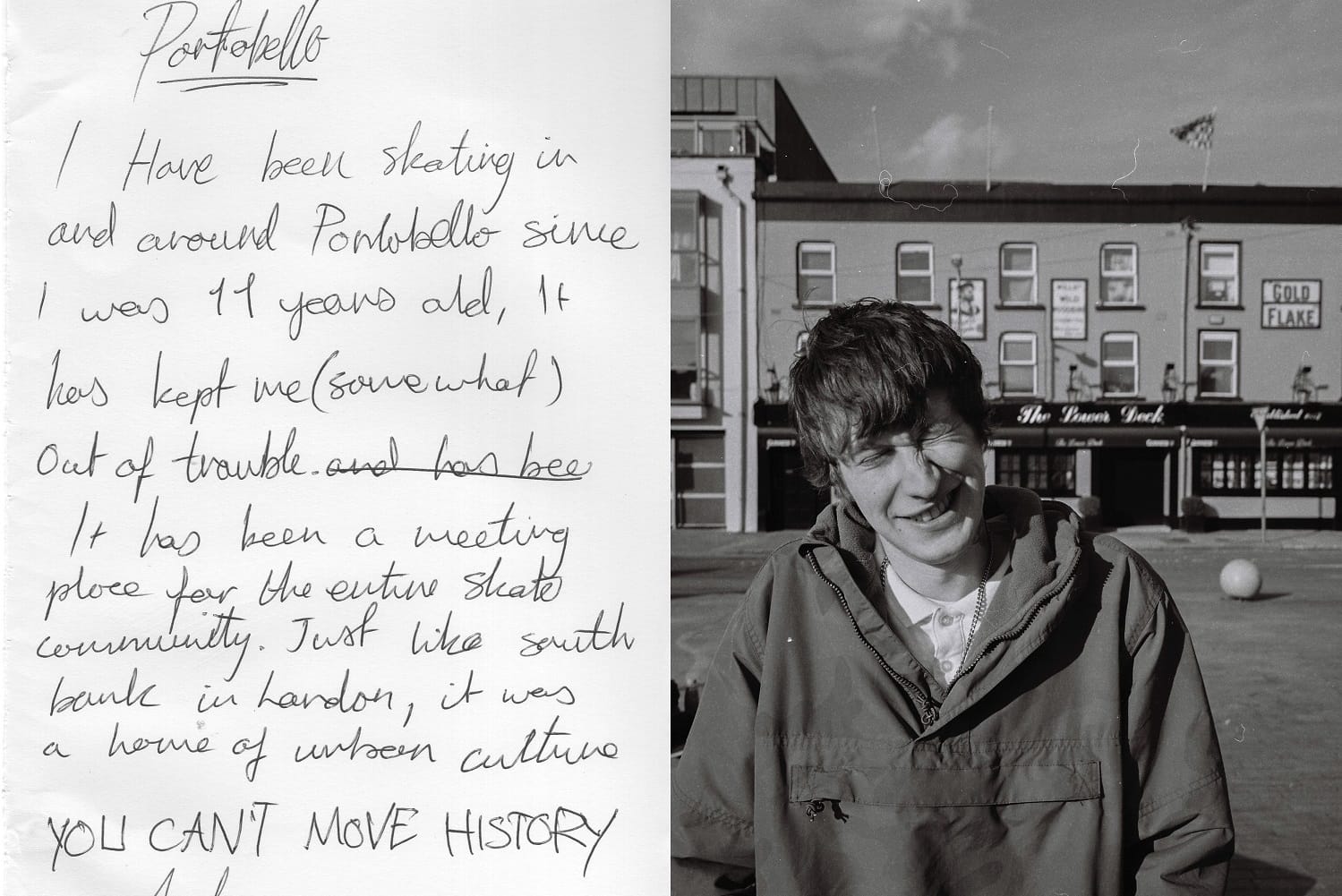

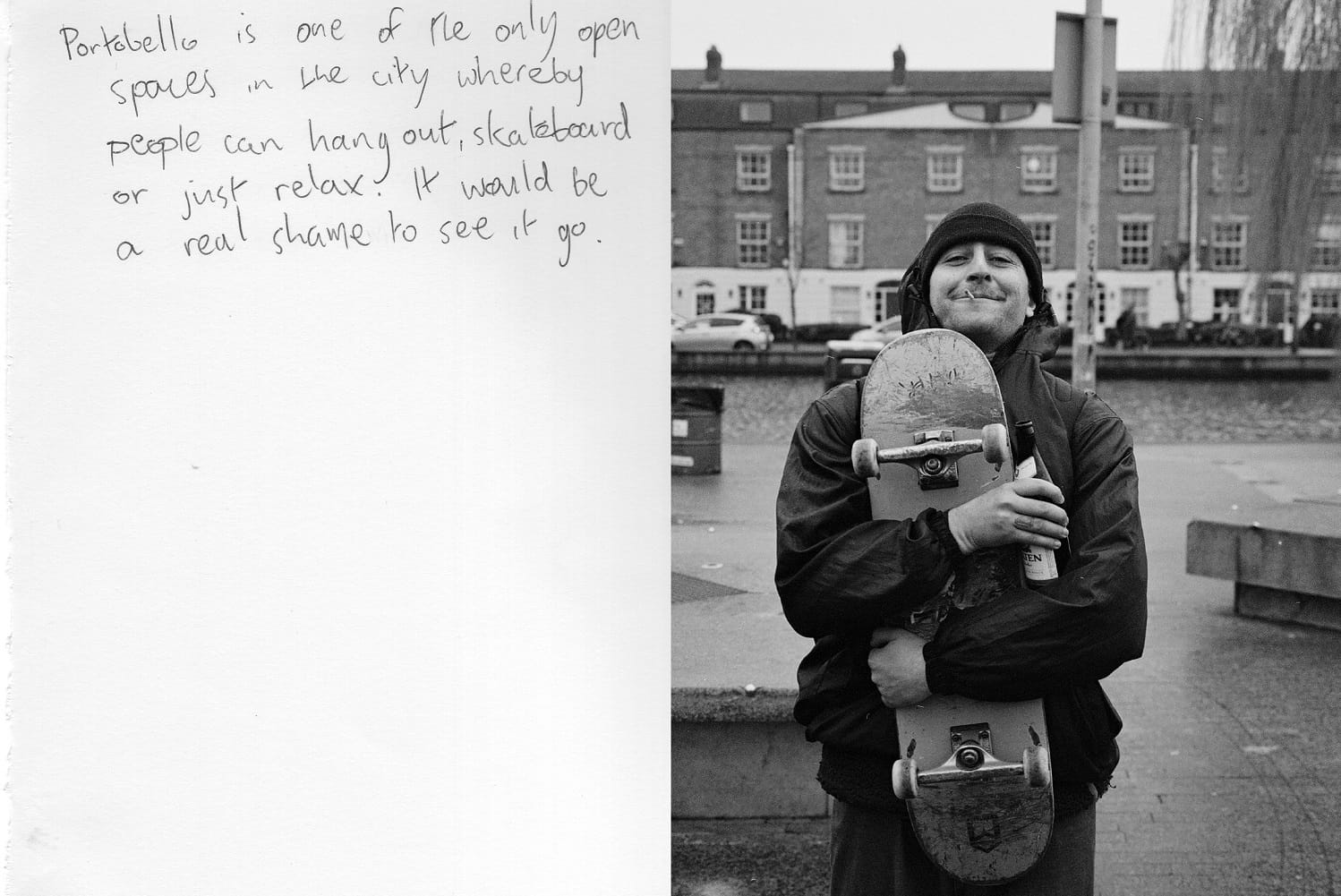

Jake Hoffman’s book features portraits of skaters, each alongside a handwritten note with their reflections on the square and its importance to them.

Photography student Jake Hoffman moved closer to Portobello last May just so he could be near the community of skateboarders that hung out by the canal, he says.

“The day before I moved to Rathmines was the day they caged the whole place up so it was a bit of a sickener as I’d already signed the lease,” he says, laughing.

Last May, the council decided to close off the square after some nearby residents complained about drinking and public urination. Then in December, builders threw up hoarding to block off most of the public space. Dublin City Council has given developer MKN Property Group permission to store construction gear on it while they build a hotel.

Last Friday at a little past midday, a painter was readying a long-handled roller to cover over messages left by disgruntled passers-by on the now grey walls that now cut through the square.

Faintly visible under a previous coat of paint is an English translation of the city motto: “The obedient citizen produces a happy city.”

Hoffman was a regular at the square long before he moved to the neighbourhood. For two years, he visited almost daily, he says, sitting on one of the grey slab benches in Portobello Square.

As part of a college photography project, he sought to capture life on the square, centering on the skateboarders.

“It was a very significant place for the past 17 years in Irish skating culture, particularly in Dublin and the street side of skating,” he says of Portobello Square, or “Ports” as it was affectionately called by skateboarders.

Portobello – The Desolation of a Social Hub and The Rejection of a Misunderstood Subculture is the result.

The photo book captures the place and its skateboarders during a period of uncertainty for Portobello Square, between its temporary closure by the council, the impact the lack of facilities was having on the place, and the ongoing uncertainty around what the hotel’s development would mean for the future.

“My project was a community’s response to the privatisation of a public space,” says Hoffman, “particularly when that space is incredibly significant to that community.”

He shot the photos with black and white film. Most are portraits of skaters, presented alongside a handwritten note with their reflections on Portobello Square and its importance to them.

“It’s almost like a yearbook,” says Hoffman of the project.

Hoffman had looked for inspiration at the format of Raised by Wolves by the photographer Jim Goldberg, a member of the Magnum agency, who paired images and handwritten accounts, he says, his cold fingers shaking tobacco out of a near-empty brown pouch.

The notes in the book reflect similar sentiments: a shared love of Portobello Square, its importance in the development of friendships, the uncertainty about its future, anger at the council for ignoring the community’s relationship with the square.

“What was once a place of joy now seems so joyless,” reads one hand-scrawled note, beside a photograph of a masked garda speaking to skaters tucking into a pizza.

“We are losing a piece of our home and identity,” reads another. “Stealing our areas for socialising highlights the level of consideration they have for us and the livlyhoods [sic] of our generation.”

“It’s a spot where you can chill and see other skaters you might not have seen for ages,” reads a scribble in sharpie.

Many notes are anonymous. As are the portraits, unless the subject signed their name.

Hoffman also opted to keep his opinion out.

“I acted myself voiceless in the project,” he says, “there’s no opening or conclusion, no manifesto by me. If I gave my opinion I think it would have taken something away from everyone’s elses.”

Hoffman originally set out to capture the demolition in 2019 of what was once the Ever Ready battery factory, on the west side of the square.

But as he got to know the skateboarders, he realised that there was another story to be told, one of a community at a particular time, under threat.

“Every time I’d go back I’d meet a new person and get to know them and it really just snowballed from there,” he says.

One reason the space is so significant to skaters, says Hoffman, is that it’s convenient. “Bushy Park is close but it’s not that close.”

Phili Halton, editor of skateboarding magazine Goblin, says that skateboarders have a long history of using Portobello Square.

He grew up in Rathmines, with the square closeby. “We would have went there every weekend until it was eventually skate-stopped,” he says, referring to the brackets and bumps that are sometimes put on public benches or street features to stop people skateboarding on them.

“You can skate at Sandyford Industrial Estate or wherever but if it doesn’t have the atmosphere you’re not going to go there,” he says.

“I’ve seen first-hand the change of what taking a public space has on young people, because a lot of people veered away toward drinking or smoking or whatever,” he says.

What was special about Portobello Square for skaters, says Halton, was its openness as a space.

Most skateparks in Ireland are fenced off, he says. With Portobello however, you could walk in and walk out so it was easy to enter, not intimidating. “It was never not available,” he says.

The importance of the square to Irish skateboarding culture was signified in the square hosting Kings of Concrete festival in 2011, says Halton. “A load of big international skateboarders came over.”

Dublin City Council actually let them take out the skate-stoppers, he says, and there was hope that the square would develop into a recognised skateboarding space. But the skate-stoppers were put back shortly after.

Hoffman hopes to release a second edition of the sold-out photo book shortly and upload the photos to his website. (He is also juggling bar work and finishing his degree.)

What’s walkable of the square these days is quiet. “I walk by and I never really see anybody here any more,” says Hoffman, gesturing around at the empty space.

A Dublin City Council spokesperson has said that the council plans to run a public consultation, starting in April this year, on the redesign of the square.

“[A]ctivities such as skateboarding will be included for consideration in the design process,” they said.

Halton, editor of Goblin, says he’s confident that skateboarders will be able to advocate to ensure that the square can accommodate them when it reopens.

He has been involved in setting up the Irish Skateboarding Association (ISA), which will soon be recognised by Sport Ireland, he says.

He wants the ISA to advocate for skateboarders, particularly with local councils, he says. “I suppose the Portobello situation is the ISA’s first real stamp upon that sort of decision-making in Ireland.”

Get our latest headlines in one of them, and recommendations for things to do in Dublin in the other.