What’s the best way to tell area residents about plans for a new asylum shelter nearby?

The government should tell communities directly about plans for new asylum shelters, some activists and politicians say.

As, over the river, councillors again picked up the thread on long-standing plans for an Irish language quarter.

As the sun was setting last Thursday, the dark green shutters over the front entrance of the Winding Stair bookshop on Ormond Quay were partially lowered.

It was just after the 6pm closing time. But a few people were still going inside.

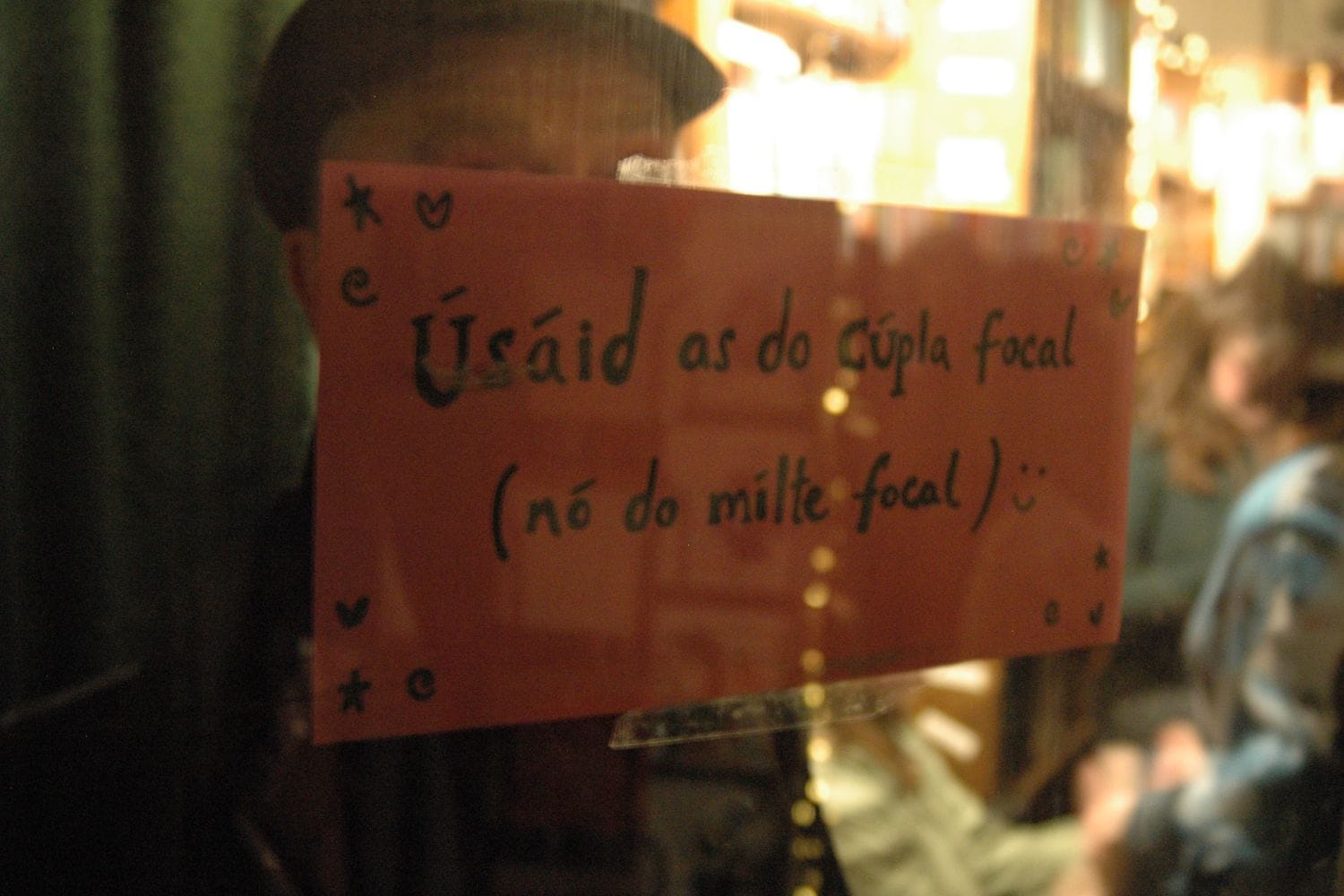

Taped to the door’s glass window was a piece of pink paper bearing a message written in Irish.

“Úsáid as do cúpla focal,” it said in black marker. “Nó do mílte focal.” Use your few words. Or your thousands of words.

Inside, the shop was warm with fairy lights and an enthusiastic bilingual babel, as about 30 people chatted away over wine and water, half in Irish, half in English.

They had come for Salon Rógaire, an Irish-language literary salon, organised and hosted by the writer and musician Róisín Nic Ghearailt.

It was the third one she had hosted since last November, she said, in between greeting people just by the front door. “This one, I wanted to get people to speak only in Irish.”

Meanwhile, across the river, Dublin City Council was also working to increase the number of opportunities to use Irish in the city, through the creation of an Irish language quarter.

The project – which has been under discussion for years, and is in the city’s development plan for 2022–2028 – was again under discussion on Thursday evening, at a special meeting of the council conducted in Irish at City Hall.

The quarter is envisaged in the area of the south inner-city between Harcourt Street and Synge Street, said Louisa Ní Éidéain, chairperson of the voluntary Irish Language Quarter Development Group.

“The vision we have is to create a cultural, inclusive quarter for everybody, whether they’re fluent or have a cupla focal or people who don’t speak a word,” Ní Éidéain says.

In the Winding Stair, about half past six, Nic Ghearailt stepped in front of the crowd.

She stood next to a leather armchair, black Fender guitar and a bookshelf stocked with various titles as Gaeilge, including a translation of Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s children’s classic, The Little Prince.

Had anyone been to a literary salon before? she asked the room in Irish. “Basically, it’s usually a curated gathering of writers and poets and performers, hosted by one person, me, an bean an tí.”

As the sign on the door suggested, everyone was encouraged to use even the few words they knew, she said. “Y’know. Go raibh maith agat [Thanks]. Dia duit [Hello]. An bhfuil cead agam dul go dtí an leithreas? [May I go to the toilet?].”

Soon, Nic Ghearailt launched into a poem by Ciara Ní É, “Leabhar Damhsa”. “It’s about the joys of getting a second-hand book and thinking about history,” she said.

Part of her reason for creating the salon was because she loved talking about and sharing books, Nic Ghearailt said after the reading. She picked up and held a copy of Queering the Green: Post-2000 Queer Irish Poetry, put together by Paul Maddern.

“I think, because we were a colonised country, there can often be the impact of looking outwards,” she said. A way of decolonising is to look inward, learning Irish and reading books published here, she said, opening Maddern’s anthology up to read from it.

All of this is her own way of trying to keep the language alive, she said, the day after the salon. “We’re in a Gaelic revival, and we’re there because of people who’ve been doing that tirelessly for decades.”

Over two hours on Thursday evening, Nic Ghearailt was joined at the front of the room by six different performers.

Singer-songwriter Amano Miura played a short musical set, airing her new single, “The Birthing House”.

It has some whistling on it, she said, teaching the crowd the melody, and inviting them to join in. “I have learned that whistling in tune, on a microphone, is the hardest thing in the world.”

Emma Ní Chearúil, presenter on Raidió Rírá, performed her translation of Phoebe Waller-Bridge’s original one-woman show, Fleabag (which was later adapted for TV).

The poet and journalist Eoin P. Ó Murchú delivered a couple of poems, one written about the Luas, another that he had jotted down on a paper coffee cup, which he read from.

And Ola Majekodunmi, the writer and broadcaster, made the bilingual night trilingual by including Yoruba in her poems “Glow” and “Lost”.

Being able to jump between Irish, English and Yoruba is just a way of encompassing who she is, Majekodunmi said, on the phone on Monday. “I only started writing bilingually since last year, because of what happened with the Dublin riots.”

One of the reasons she started the salon, Nic Ghearailt said, was that she wanted to celebrate the city’s Irish language scene.

“It is absolutely amazing in Dublin, and I’m always looking around, wondering who else is writing funky little poems as Gaeilge?” she said.

According to the 2022 census, 162,400 people over the age of three could speak Irish in Dublin city, which was up from 156,400 in the 2016 census, according to the Central Statistics Office (CSO).

And in Fingal, there were another 113,000, up from 100,000 in 2016, according to the CSO.

What’s vitally important, though, is trying to find people you can speak the language with, Nic Ghearailt says. “You need the space for it to be a living language. A social language.”

Later that day, Dublin City Council held a special meeting entirely in Irish, at which Darach O’Connor, the executive manager of Gaeilge 365, Dublin City Council’s project for promoting Irish, echoed Nic Ghearailt’s point.

Since 2006, the number of people who can speak Irish in Dublin has increased by 14 percent, he said. “But in contrast to that, people are saying that they don’t have the opportunities to use the language.”

So, the number of people actually using it in Dublin has fallen by 5 percent over that same period of time, he said.

One of the sentiments being used a lot is that Irish is “having a moment”, he said. But that’s not entirely true, he said.

It’s getting more popular. But there’s still a bit of a way to go before it really peaks.

“There is a movement at the moment. And we are at the start of a very special time, and a very interesting time for the Irish language,” O’Connor said.

Through its greater usage by musicians, podcasters and social media influencers, it’s become cool, he said. “The youth have a great energy about them”

And one of the initiatives that the council is looking to develop to contribute to this movement is a Gaeltacht in Dublin.

The council is proposing to set up an Irish Language Quarter around Dublin 2 and 8, said Louisa Ní Éidéain, chairperson of the Irish Language Quarter Development Group.

This Gaeltacht area would stretch from Harcourt Street to Synge Street, with hopefully the Iveagh Gardens, National Concert Hall and Kevin Street Library participating, she said.

“We think there are about 2,000 people in the area already speaking Irish weekly between education, entertainment in their communities,” Ní Éidéain said.

The foundation for the quarter is already in place, as it is an objective in the city’s development plan, she said.

A cross-organisational working group is preparing a detailed plan for the quarter, according to a management report for the council’s Community, Gaeilge, Sport, Arts and Culture Strategic Policy Committee, from 16 December.

There isn’t a timeline as of yet, she said. But as part of the quarter the Office of Public Works is in the early process of refurbishing the Irish Language Centre at 6 Harcourt Street into an “Irish cultural hub”.

“There is a three year estimate, at the moment, with regards to the development that is happening at Harcourt Street,” she said.

City Arts Officer Ray Yeates said it is important to be realistic about this plan, he said. “It would be wrong at this stage to say what road we will take.”

They will need to carry out studies, he said. “So patience is, of course, the most important thing here.”

But the councillors will have to make a decision, he said.

CORRECTION: This article was updated at 12.54pm on 27 March 2025 to reflect that it was Ciara Ní É who wrote the poem “Leabhar Damhsa”, not Róisín Nic Ghearailt. We apologise for the error.

Get our latest headlines in one of them, and recommendations for things to do in Dublin in the other.