What’s the best way to tell area residents about plans for a new asylum shelter nearby?

The government should tell communities directly about plans for new asylum shelters, some activists and politicians say.

Honour Bright was found dead in Ticknock, Co. Dublin, in June 1925.

The plaque sits at the base of a big stone wall on Ticknock Road, a narrow carriageway off the busy M50 that winds gently southwards past hedgerows and fields and standalone big houses.

“Honour Bright 9 June 1925 Rest in Peace,” the carving reads.

Next to the plaque on Saturday lay a wreath of colourful faux flowers and a fractured plastic plant pot.

It marks the spot where, 98 years ago, a worker leading his horses from Dundrum to Ticknock in the early morning discovered the body of Lizzie (Lily) O’Neill – who went by Honour Bright.

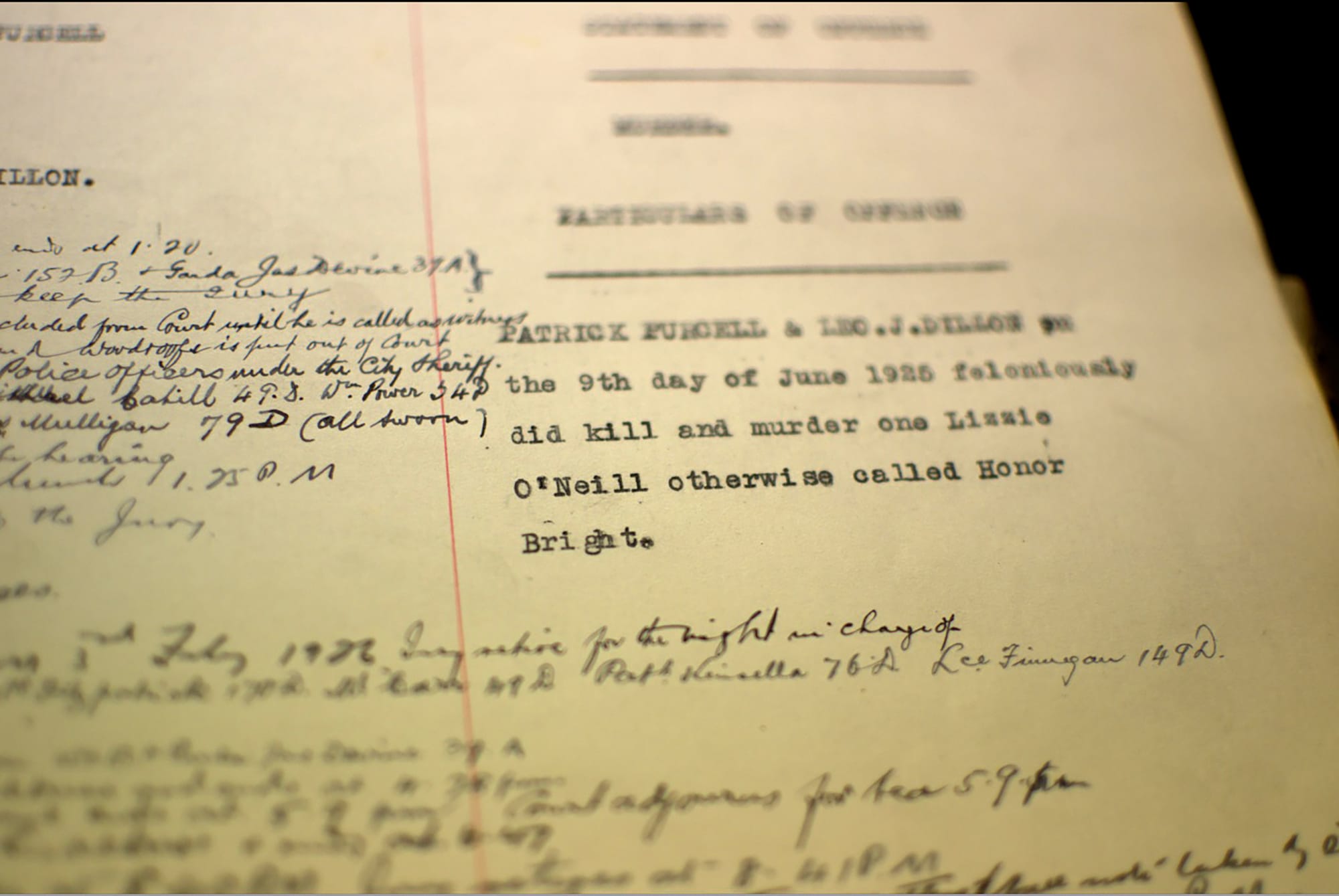

Two men were tried for her murder but were found not guilty by a jury, according to handwritten records of the proceedings at the Central Criminal Court.

Decades after their acquittal, Patricia Hughes, O’Neill’s granddaughter, went on an odyssey, mining the past for answers.

Her search for closure had been passed down from her father, Kevin Barry O’Neill, who searched and searched until he died in 1980.

Hughes had asked An Garda Síochána to release police records about the murder, with no luck.

She wrote to the Garda Commissioner in 2019 – and others too, even through the early months of the pandemic – and asked for a fresh investigation, but didn’t seem to have gotten the response she wanted, according to correspondence she had uploaded online.

Hughes constructed her own theories and wrote a few books to try to make sense of the past. She died on 4 December 2021 in the United Kingdom.

A spokesperson for An Garda Síochána said on Sunday that it had forwarded queries about the investigation to its district in Dún Laoghaire, which covers Ticknock.

The worker who found O’Neil’s body in Ticknock thought she was fast asleep on the side of the road, says a book by John Finegan, a journalist who worked for the Evening Herald at the time.

He strolled past her at first, it says. Then walked back to see if a patent-leather shoe he had stumbled upon belonged to her. “It was then he saw a trickle of blood oozing from the pink blouse,” writes Finegan.

Before a bullet pierced through her and lodged into her heart in June 1925, O’Neill, a single mother, lived in Newmarket, near the Coombe. She relied on sex work to support herself and her small boy, Kevin, who was then almost five.

Her last known client was Leo J. Dillon, a 25-year-old Garda superintendent, who had travelled to Dublin from Co. Wicklow, mainly for police business, but went on a bender with his friend Dr Patrick Purcell and, according to his testimony had sex with O’Neill in the early hours of 9 June 1925.

The gardaí said they found five shillings and a half-penny in the pocket of O’Neill’s well-worn grey tweed jacket. That was how much Dillon had on him that night. She was two days shy of turning 25.

Dillon and his friend Dr Patrick Purcell were tried for her murder.

During the trial, O’Neill’s roommate Madge Hopkins, who was with her on the night of the murder, said that Purcell had been ranting about being robbed by another woman.

He had said that if he saw the woman again, she said, he would “do her head in”. That he had a garda friend who could “blow them all off the Green”, Hopkins said.

A coach driver also said in court that he had heard Purcell saying if he found the woman, he’d take her to the countryside and put a gun in her mouth. If he didn’t, he’d do it to another woman of her kind, the coach driver said.

Purcell dismissed the story about the woman as a “drunken bravado”. He said he’d made up the whole thing, and no one had taken his money that night. He couldn’t remember how many drinks he had had, he said, but that it was more than 12.

Gardaí dismissed Dillon from the force shortly after the murder, according to his file, now at the National Archives on Bishop Street.

But Dillon and Purcell were found not guilty in February 1926, according to handwritten records of the proceedings at the Central Criminal Court.

Cian Ó Concubhair, assistant professor in criminal justice at Maynooth University, says that in the early days of the Irish Free State, An Garda Síochána was ill-equipped to carry out murder investigations.

“If you look carefully back on the history of the criminal justice system, it was very crude, a lot of injustice, a lot of wrongful convictions, a lot of brutality,” he says.

For the public, he says, examining legacy cases that are still open – like O’Neill’s – can help pierce any nostalgic romanticised image of the past’s police force as no-nonsense and highly competent.

“That in the good old days, the police were, you know, they were tough and really well motivated and competent,” he said.

It is hard to get convictions over the line after such a long time, says Ó Concubhair. Even without a criminal prosecution though, there are other ways to help families who are searching for answers and closure.

“The narrative is that the only way you can get real accountability or real justice is through criminal prosecution, I’m not convinced it’s necessarily the best way to get it,” he said.

Getting a form of closure and a feasible version of truth goes a long way, he said. “People getting some kind of truth, I think it can be really valuable and healing for the families.”

In the early hours of 9 June 1925, O’Neill met Dillon, the Garda superintendent, and his doctor friend Purcell outside the Shelbourne Hotel on the north side of Stephen’s Green.

In his book, Finegan, the Evening Herald journalist, writes that O’Neill usually strolled Grafton Street towards Stephen’s Green in search of clients.

Hopkins, O’Neill’s roommate and colleague, who went by Bridie, said that the last time she saw her, she was in a grey two-seater Swift car – which belonged to Purcell – with Dillon.

Dillon told the court that O’Neill was the only woman he had sex with that night.

According to witnesses, O’Neill rushed out of the two-seater car at around 3:15am and got into a cab that drove off towards Lower Leeson Street.

During the trial, Dillon said O’Neill had asked him to drive her home. But he refused because the car belonged to Purcell, and he thought it’d be impolite to use it, he said.

Later, it was revealed that O’Neill and the taxi driver she was last seen with knew each other. His name was Ernest Hamilton Woodroofe, a Dún Laoghaire local.

Lucy Smyth, director of Ugly Mugs, a non-profit that offers an app aimed at improving the safety of sex workers, says it’s a pity the investigation at the time didn’t take a closer look at Woodroofe.

“The last confirmed sighting of Hono[u]r was getting into Woodroofe’s taxi,” said Smyth in an email earlier this month.

“Woodroofe be excluded from court until he is called as a witness,” says a scribbled note on the records of the proceeding.

During the trial, a witness said she’d spotted Woodroofe with a revolver sometime after O’Neill’s murder in the summer of 1925.

Woodroofe said in court that he drove O’Neill through Merrion Row and the Grand Canal and waited for her on Harcourt Road as she got out for about a minute and back in.

Then they drove through Harrington Street and South Circular Road, and he dropped her off on Leonard’s Corner, about a mile away from her house in the Liberties, said Woodroofe.

During the trial, Woodroofe said he didn’t rely on his taxi for income. He had a bike shop and independent means, he said.

When counsel asked him if that meant he didn’t mind giving women a lift without charging a fare, he stayed quiet.

When asked if he knew that one of the coach drivers had said they’d seen him trying to pick up Hopkins, O’Neill’s roommate and colleague, he just said he wasn’t aware of that.

He said he had known O’Neill for six months and that she called him Jimmy even though that wasn’t his name. He didn’t know why, he said.

An article in the Evening Herald dated 28 October 1925 suggests that Woodroofe may have been in the habit of picking up women for enjoyment without charging a fare.

Just a few months after O’Neill’s trial concluded, Woodroofe presented before a High Court judge at Dublin Castle over alleged breach of promise of marriage to Margaret Owens, says the article.

Woodroofe had claimed Owens waved his taxi over somewhere in Co. Wicklow back in the middle of August 1924, it says. But Owens disputed this account, saying she was in England at the time and only returned in the following September.

She said Woodroofe pulled over and offered her a lift home and then began visiting their house often and later proposed marriage, which she accepted. He showed up to their house twice a week after that, it says.

Woodroofe denied promising marriage to Owens and claimed he saw her casually. Owens said he had tried to intimidate her into settling out of court.

He had called into her house with four men pretending to be Garda detectives, but her parents were fortunately home at the time, says the article.

“Defendant informed plaintiff that the ‘detectives’ had arrested him for complicity in the Ticknock murder,” it says.

The article does not say that Owens claimed to have given birth to Woodroofe’s child but quotes a barrister as telling the judge, “Your lordship has a very good idea why the matter is urgent.”

Owens gave birth to a baby boy called Ernest – Woodroofe’s first name – in June 1925, the same month O’Neill was murdered, according to a birth certificate that does not list the father’s name.

Woodroofe died six years after, on 14 March 1931, at a YMCA hostel, according to probate records.

Smyth, the director of Ugly Mugs, says fragments from Woodroofe’s life, including his death at a YMCA hostel, his behaviour as a cab driver, his fraught relationship with Owens and the birth of the child, made him worthy of more examination.

Hughes, O’Neill’s granddaughter, never believed that she relied on sex work to make ends meet.

In a letter dated 16 April 2020, she wrote to the Director of the Public Prosecutions (DPP), saying her father had travelled to Dublin in 1961 and sought answers from the Gardaí.

She didn’t get those, though. And chewing over the family’s pain for so long, somehow, she’d come to believe that the late poet W.B. Yeats had impregnated her grandmother, that her father was his son and a conspiracy led to her death.

Hughes doesn’t offer anything in her books to back up those claims, simply joining the dots between snippets of Yeats’s life and those of her grandmother and drawing conclusions.

Smyth, the director of Ugly Mugs, says she doesn’t believe in Hughes’ theories – although she doesn’t like calling her a conspiracy theorist – but says she should have been treated with kindness as a woman desperate for answers.

“And she was hurt, and nobody like the gardai would give her the answers she so desperately wanted,” said Smyth.

In one of her books, Hughes suggests she was hopeful that seeing the police records would back up her theories or perhaps debunk them – and the refusal had her nursing suspicions.

“The police records of this case of ninety years ago have never been released despite many requests,” she wrote.

A lack of information, Smyth says, compounded Hughes’s paranoia.

Gardaí should have tried to give her some answers, Smyth says. “Pain needs to be acknowledged sometimes for people to move on.”

Get our latest headlines in one of them, and recommendations for things to do in Dublin in the other.