What’s the best way to tell area residents about plans for a new asylum shelter nearby?

The government should tell communities directly about plans for new asylum shelters, some activists and politicians say.

“Do art and housekeeping mix?” a 1963 article on Marianne Ågren-McElroy mused. “Some people would say that they don’t – especially long-suffering husbands.”

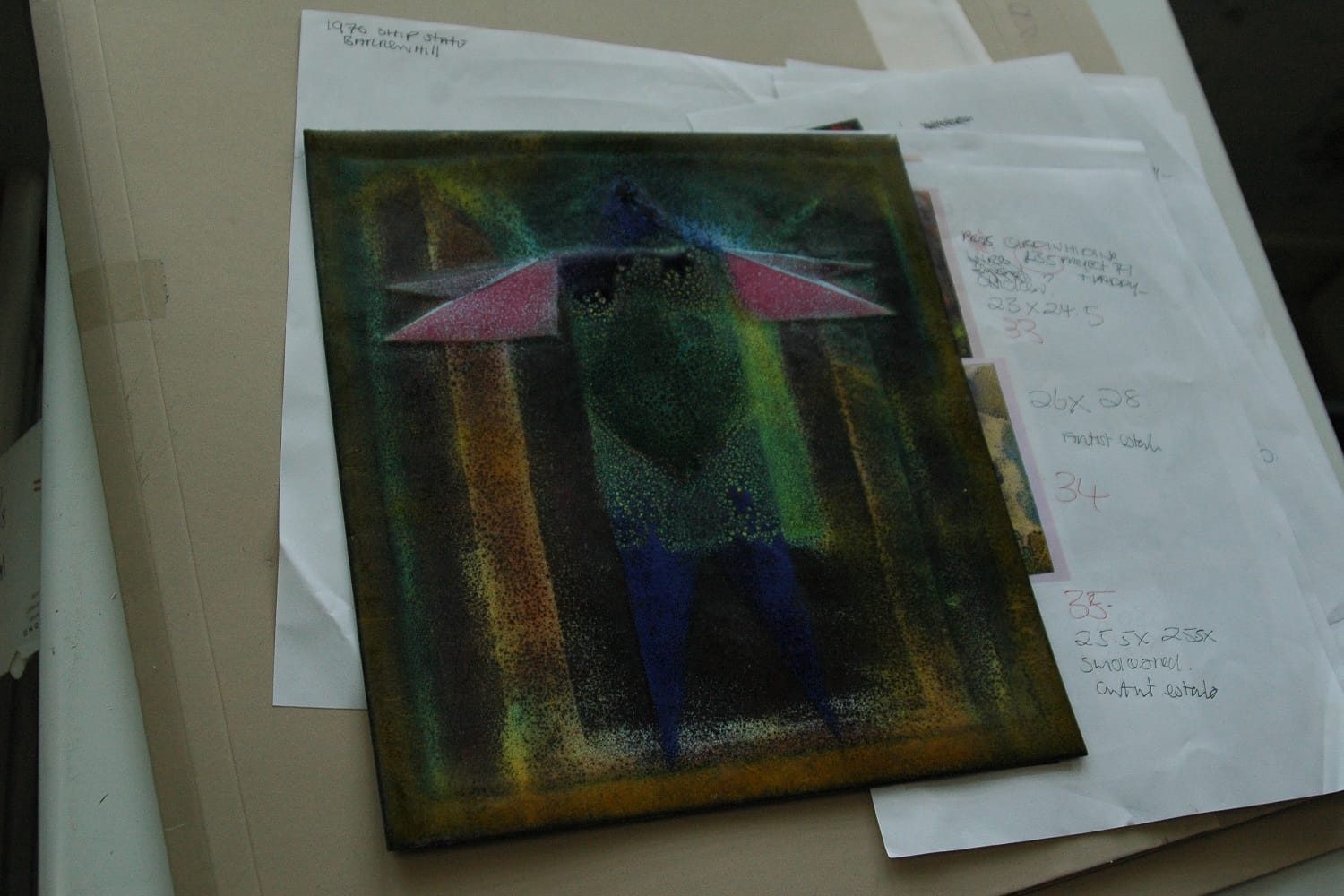

Kristina McElroy reaches into a clear plastic box. She delicately stacks six thin ceramic slates on the desk in front of her.

Most of the slates are square. About 25 centimetres long and the same wide. Each is decorated in figures or objects, altered into near-abstraction.

The pieces strike a sombre tone. Murky green squares join with grainy pink triangles to imitate a body of sorts. Hazy lines of red, blue, white and green bend upwards like a spider plant.

The works are by Kristina’s mother, Marianne Ågren-McElroy. Kristina’s office in Drimnagh, has become something of an archive, devoted to her body of work.

There are framed paintings propped against a closet, stained glass window-like landscapes and delicate inky patterns in monochrome and gold, echoing the form of Japanese ukiyo-e prints.

In big cardboard folders are creased and yellowed loose sheets of paper, showing surrealist figures in watercolours, pastel portraits, and Biblical scenes in pen, their faces and bodies heavily stylised.

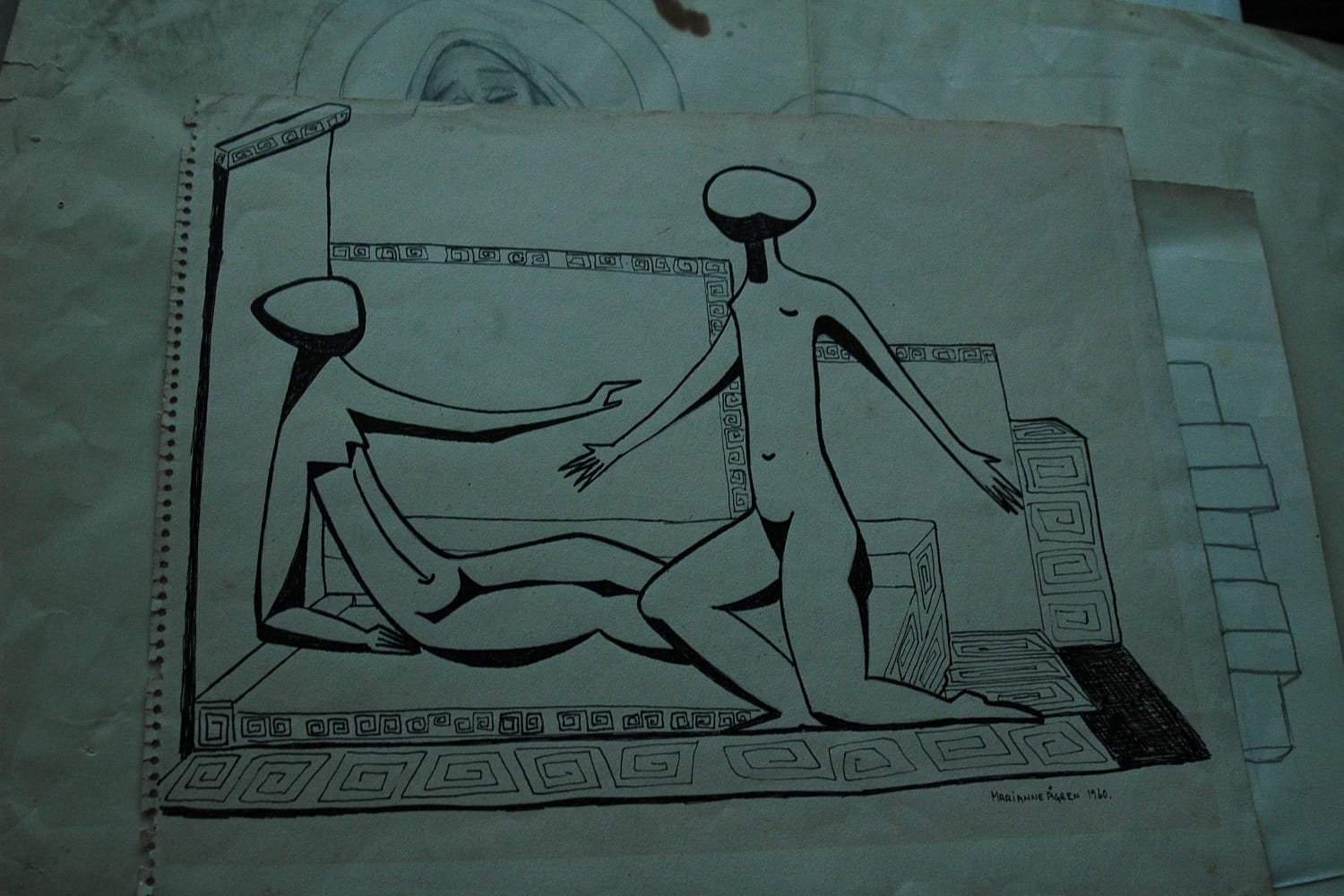

“I love this,” says Kristina, excitedly. “Have you ever seen The Annunciation like that before?”

She looks down at a sketch from 1960. Drawn in black felt tip marker, it shows the moment when the Angel Gabriel tells Mary that she is to be Christ’s mother.

Both Gabriel and Mary are faceless and nude. The angel is wingless as he kneels. Their heads are horizontal ovals and cast thick shadows over their bodies.

Though a prolific artist who exhibited in Dublin throughout the 1960s and ’70s, Marianne Ågren-McElroy had faded into obscurity by the ’80s.

“She’s just a mystery now,” says Kristina McElroy. “If you were a female artist then, you can be really quite ignored.”

To rectify this, Kristina has been preparing a photobook, and a retrospective at the United Arts Club on FitzWilliam Street, scheduled for March.

The show will include works from the collections of Ågren-McElroy’s two daughters, Kristina says. “I just want to put her work into a context before they disappear.”

Over coffee, McElroy sifts through another box, containing slim strips of paper, on which her mother sketched and painted out the ideas that became her ceramics.

The small pieces of paper are no larger than three or four film negatives in a camera.

In the pile of works-in-progress is a hefty folder with newspaper clippings, detailing Ågren-McElroy’s life in the words of herself and her critics.

Marianne Ågren was born in Lidingö, a Swedish island just east of Stockholm. It was, she told Woman’s Way in 1967, “a kind of floating Ballsbridge”.

Her mother was from Lapland and her father from Gothenburg, she told the magazine.

From an early age, she had an interest in the arts. “She really, really wanted to go to art college in the 1940s, and her mother actually said to her, ‘Nice girls don’t do that kind of thing,’” says Kristina.

Instead, during the Second World War, she went to university in Stockholm to study English. “She was very pro-Allies, and helped her father arrest a gang of Nazi spies in Lidingö,” says Kristina.

Post-war, she studied drawing in Paris, worked with Stockholm’s Save the Children fund, and finally entered the Swedish Ministry for Foreign Affairs. “To see the world,” Ågren-McElroy told Woman’s Way.

In 1950, she moved to Dublin, a biographical note from one of her exhibition programmes says. Here, she worked at the Swedish embassy as a secretary to the ambassador.

Two years later, McElroy says, she married Patrick McElroy, and they lived together on Beaumont Avenue in Churchtown. An artist from Inchicore, Patrick McElroy worked mainly with metals and enamels.

Said Ågren-McElroy, in a hand-typed single-page autobiographical note: “Although married to an artist, we keep completely separated identities as artists.”

Patrick McElroy taught at the National College of Art, while Ågren-McElroy balanced her career as an artist with a full-time secretarial position in the Swedish embassy.

“It was unusual, when I was a child, to have a mother working full-time out of the house,” says Ingrid McElroy, her other daughter.

“She also took on freelance work as a translator,” says Ingrid. “Not just nice things, like poetry. But technical reports about traffic lights too.”

Kristina, as her cat sprawls across the media clippings folder on her kitchen table, pulls out a letter, dated October 1966. It is from the then Irish Times literary editor Terence de Vere White, asking if her translation of a German poem could be featured as one of the paper’s Saturday Poems.

When her career as an artist began to take off in the ’60s, the attention she drew tended to fixate more on her dual life as both an artist and wife.

Interviewed in the Evening Herald in December 1963, the feature ran with the bemused headline: “These Housewives Are Artists in Their Spare Time.”

“Do art and housekeeping mix?” the article reads. “Some people would say that they don’t – especially long-suffering husbands.”

Being a mother of three with a full-time job did tend to steal attention away from her work, Ingrid says. “She was an attractive woman, and yeah, I think the focus went to that.”

By Ågren-McElroy’s own account, her primary influences were Sweden’s landscapes, their mountains, primal forests, and the lush plains around where she grew up, she wrote.

“[Especially] the landscapes half covered with snow which makes just a few details stand out stark against the infinite white,” she wrote.

What frustrates Kristina upon reflection, however, is how shallowly her work could be viewed by the foremost art critics of the day.

In her office, she lifts a black glazed ceramic sculpture from a box. The piece is heavy and she lugs it over to her desk.

About 40cm tall, and 20cm wide, the statue depicts a young boy. He is seated on a square piece of wood. His body is warped as if it were composed only of internal organs. Both of his arms are stumps. His left foot is missing, and his head is tilted upward.

Looking through a pair of vacant eye sockets, he appears to shout from a perfectly circular mouth.

Ågren-McElroy sculpted the figure, titled “Charlie Baby”, in 1968. Depicting a boy as he begs, the work was her means of attacking the US war waged in Vietnam.

It was exhibited in Dublin and Galway that year. “The only review didn’t know that it was an anti-war piece,” Kristina says, smiling exasperatedly.

She produces this review, which infuriates her. Printed in the Irish Press on 8 May, critic Raymond Gallagher said of “Charlie Baby” only that it was “a Freudian’s delight, no matter what it represents”.

Four months later, Ågren-McElroy was similarly sold short at her first and only solo exhibition in the Project Gallery on Lower Abbey Street.

The show was composed of ceramic sculptures more abstract than “Charlie Baby”. Enigmatic and spherical, featuring frost-like carvings etched into their surface, Kristina likens the work to that of modernist sculptor Barbara Hepworth.

But again, the reviews didn’t seem keen on delving too deep. Writing in the Irish Times, Brian Fallon said, “though the titles [of her work] do not suggest it, this critic … admits to finding several of them overly erotic.”

Remembering how her mother felt at the time, Kristina says the reviews startled her. “She was upset. Like, ‘Overly erotic, what is he going on about?’ They weren’t. They were abstract.”

In the early 1970s, Ågren-McElroy continued to exhibit in group shows. She represented Ireland at the 1972 International Ceramics exhibition in the Victoria and Albert Museum in London.

Many of her works were purchased by private buyers in Ireland and abroad, a biographical note from one exhibition says.

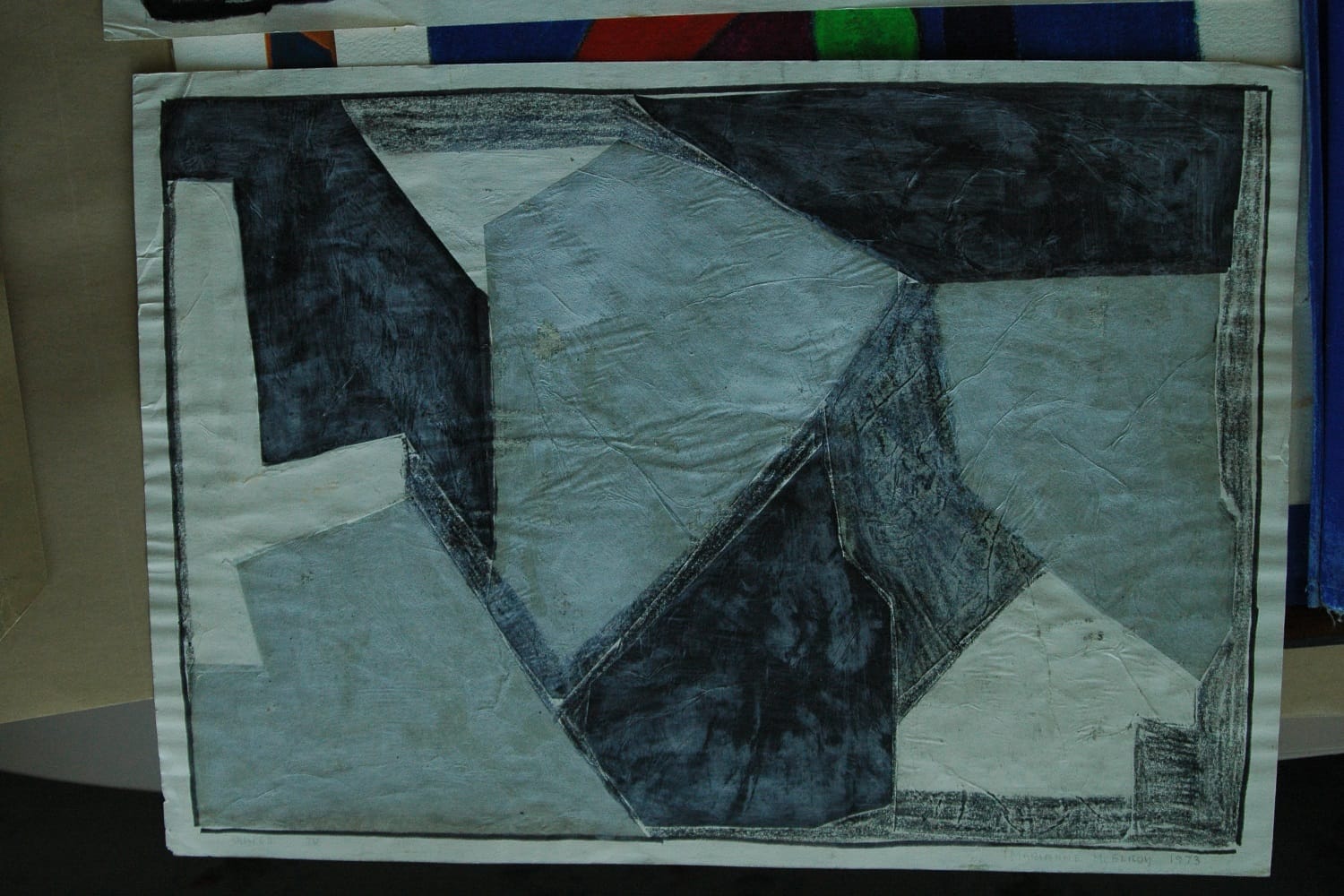

Two of her works, a collage from 1973 and an enamel from 1976, were acquired by the Arts Council, says a spokesperson for the council.

They remain in storage, and are ready to be loaned out to organisations for exhibition or long-term display. Unfortunately, the spokesperson says, there is no public access.

One of her final shows in Dublin was staged at the Emmet Gallery on Lower Exchange Street between September and October 1976. The exhibition paired her own work with that of her husband.

Their marriage had broken down at this stage, Kristina says, “and the show was almost a soap opera”.

“It was very, very difficult to be a separated woman at that point,” she says.

In the 1980s, she returned to Sweden, Kristina says. “She began to work, and [had] a series of strokes.”

It was a difficult period for her, and in the 1990s, she returned to Ireland. On 11 November 2006, she passed away in St James’ Hospital.

The sheer breadth of styles Ågren-McElroy adopted over her lifetime is remarkable, Kristina says. “She hasn’t got one genre.”

Kristina’s idea for the exhibition, due to run between 11 and 13 March at the United Arts Club, and an accompanying photobook, titled Mrs. Artist, is to add clarity to the little that is public about her mother’s life.

“It’s about filling in those gaps,” she says, and reminding people that her mother was a vital contributor to Dublin’s modernist arts scene.

The sisters tried to find a gallery or a museum that might take the works and her archive to no avail, Ingrid says.

“Kristina’s idea was to at least have some photographic records of her work, because there should be a legacy,” says Ingrid. “So that in 20 years time if a student comes across her, and wants to write something, there will be a track record there.”

Get our latest headlines in one of them, and recommendations for things to do in Dublin in the other.