What’s the best way to tell area residents about plans for a new asylum shelter nearby?

The government should tell communities directly about plans for new asylum shelters, some activists and politicians say.

In 2017, emails and memos from officials at the Department of Public Expenditure suggest they were unconvinced of the need for affordable-housing schemes.

In 2017, officials at the Department of Public Expenditure seemed unconvinced of the need for affordable-housing schemes at that time and said no money was available to fund them, show emails and memos between its officials and those in the Department of Housing.

After an earlier attempt to fashion an affordable-housing scheme based on cash subsidies fell apart a year earlier, the Department of Housing came back with an alternative model based on using local-authority-owned land to subsidise new homes.

This one would be based on leveraging state land for affordable-purchase and affordable-rental homes, said department officials in a draft policy paper that was being revised in September and October 2017.

At the heart was the question of “how the scheme would be paid for as there is presently no budget available for the scheme”, an issues note in March 2017 had said, as discussions started on what form a new scheme might take.

The Department of Housing would have to make the case for more funding, or if it was done through local authorities, they could do what they want “as long as what is done does not impact on the government balance sheet”, it says.

“Likely to Increase”

The Department of Housing’s draft policy paper from October 2017 notes growing challenges around housing affordability and a growing burden on tenants in the private rental homes, who spend more than twice as much of their household budget on rent than they did in 1987.

“Unaffordability is likely to increase in the medium term,” the paper says. Unchecked, it could have knock-on effects of social exclusion and divided cities.

The draft paper diagnoses the decline in affordability as mainly stemming from “the high and rising price paid for residential development land and the cost charged for accommodation relative to other prices, particularly wages”.

The gap between the cost of housing and wages “results significantly from the increased dependence on the private market for housing provision”, it says. “Most of the substantial historic public investments in supply-side subsidies to housing have not resulted in a proportionate permanent capacity of the state to provide low-cost housing.”

Selling off social homes to people living in them – through what is known as the tenant purchase scheme – helps individual households and can anchor people in communities, but over time this has meant that dwellings “entered the private market and will command market prices”. (An earlier version phrased this as “may now command the same prices that drive unaffordability”.)

“The loss of social housing assets, coupled with the current low level of investment in the third sector – not-for-profit housing provision, has limited the housing systems’ capacity to provide reduced cost housing,” the note says.

Dependence on the private-rental sector for social housing – through schemes in which the state subsidises tenants’ rents – has gone up. The high market rents in Dublin “drive up the cost per recipient of such social housing” and the use of demand-side subsidies in a squeezed market “has the potential to put further upward pressure on rental prices more generally”.

The number of households that can’t affordably meet their own accommodation is growing, it warns. “But the state may be unable to provide rental solutions given the lack of available affordable properties.”

It notes a range of measures that the government had taken to date, to try to make homes more affordable.

Those mentioned include the fast-track An Bord Pleanála process for large developments, changed apartment standards, and cut development levies.

It also highlights the €226 million Local Infrastructure Housing Activation Fund (LIHAF), and how local authorities were “bringing land to market”, and the vacant sites levy, too.

Finally, it mentions the Help to Buy scheme, a pilot scheme for “starter homes” at O’Devaney Gardens in central Dublin, and a cost-rental pilot by the Housing Agency and Dún Laoghaire-Rathdown County Council at Enniskerry Road, as well as rent-pressure zones.

But while statistics show a “significant scaling up” of building, the figures are low in Dublin – with limited affordable new homes to purchase, and limited supply in the rental market, it says.

Given high rents and purchase prices “there is a clear case to be made that the market is failing to meet the housing access and affordability needs to households with annual income of less than €82,000”, it says.

The Department of Housing document also notes that exchequer funds are still very scarce and must be carefully managed. So the government is committed to “supporting households, in most need, utilising the scarce resources available, optimally”.

State-owned land is a key resource that must be leveraged to provide homes at more affordable prices, it says. Councils have 700 sites, with space for conservatively 37,500 new homes, it says. (Some is already designated for social housing, and some is not serviced and ready for development.)

So there need to be more state interventions to put affordable-rental and affordable-purchase homes on state lands in Dublin, and “to increase the proportion of public housing within the overall housing stock”, it says.

The aims of the Department of Housing’s affordable-housing programme would be to increase home ownership in appropriate locations for target groups, build a substantial cost-rental sector, and build affordable housing near public transport, jobs, and services. (Cost-rental homes are homes whereby the rent is set based on the cost of construction.)

Providing access to affordable housing nearer to Dublin and other cities would counter the danger of them “becoming homogenised by virtue of income and affordability where lower income groups, other than those who qualify for social house support, are effectively excluded from living in parts of our cities”, it says.

Listed next steps included reintroducing the affordable-housing purchase scheme that operated in the past. The Department of Housing also looked for an exchequer fund of €25 million for local authorities to put in infrastructure on their land to make homes more affordable.

The department said it wanted to develop a number of cost-rental pilots, and affordable-purchase pilots, too.

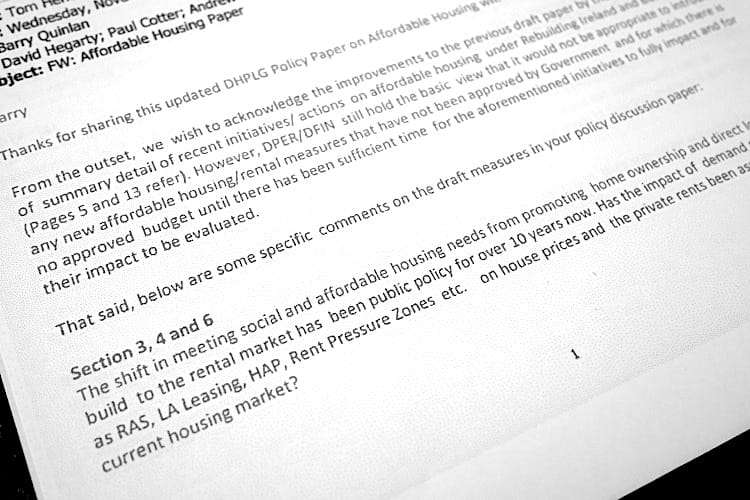

On 12 October, an email from Barry Quinlan, a principal officer in the Department of Housing, mentions early concerns from the Department of Public Expenditure and the Department of Finance about announcements around affordable housing.

“[T]hey have concerns around the expectations we are potentially creating versus the quantum of affordable housing we will be able to provide”, as well as viability of cost-rental on state lands, and concerns about the government’s general balance sheet, Quinlan wrote.

Later feedback from Tom Heffernan, a principal officer at the Department of Public Expenditure on 29 November, said that it welcomed how the draft policy paper mentions existing initiatives under Rebuilding Ireland, the government’s housing plan, taken to bring about affordable housing.

But the Department of Public Expenditure and the Department of Finance held the view that “it would not be appropriate to introduce any affordable housing/rental measures that have not been approved by Government and for which there is no approved budget until there has been sufficient time for the aforementioned initiatives to fully impact and for their impact to be evaluated”.

Heffernan also queried whether the Department of Housing had assessed the impact on house prices and private rents of the shift in policy from directly building social and affordable housing, to giving people subsidies to help pay their rent in the private market, which “has been public policy for over 10 years now”.

A review of Rebuilding Ireland had said the focus should be on increasing overall housing supply and building social housing. All indicators for those “are positive”, Heffernan wrote.

He suggests that LIHAF should have “a significant impact on the supply of affordable homes in the medium term”. (Some have questioned the extent to which LIHAF will result in affordable homes.)

The Department of Housing’s policy paper didn’t make a strong enough case for an affordable-purchase scheme on top of a home-loans scheme, Heffernan also wrote.

He also noted that any cost-rental scheme would need “a very considerable Exchequer commitment”, so any pilot would have to be have to be “rigorously evaluated before roll-out”.

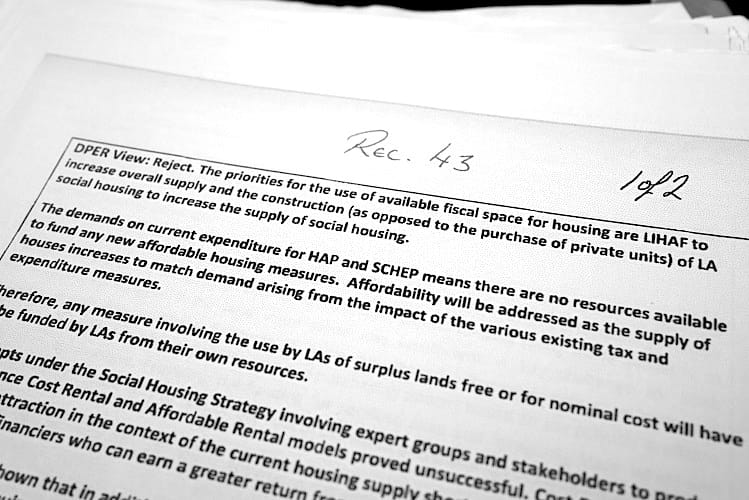

Earlier in the year, in September 2017, the Department of Housing had submitted a number of draft measures under the review of Rebuilding Ireland. It got feedback on those, too, from the Department of Public Expenditure.

They included the desire to bring in a low-cost serviced sites initiative for “regeneration areas” in Dublin city and other places, to allow for schemes similar to the Ó Cualann Co-housing Alliance project in Ballymun, which delivered homes for €140,000 to €219,000.

Roughly 530 affordable homes could be delivered with €20 million in investment, if there were €50,000 to service each site split between local authority and exchequer funding, the Department of Housing said. That €20 million could be redirected from a proposed affordable-housing scheme that had been shelved in 2016, the Department of Housing said.

The view from the Department of Public Expenditure was that exchequer capital funding, other than for LIHAF, was only available to meet social-housing needs. “No funding is available for affordable housing schemes for persons above income eligibility limits for social housing,” was its verdict.

It said local authorities could sell surplus land, or provide the land at below cost to provide affordable housing as long as it didn’t cost the exchequer anything and the local authority bore any loss involved.

Reject, Reject, Reject

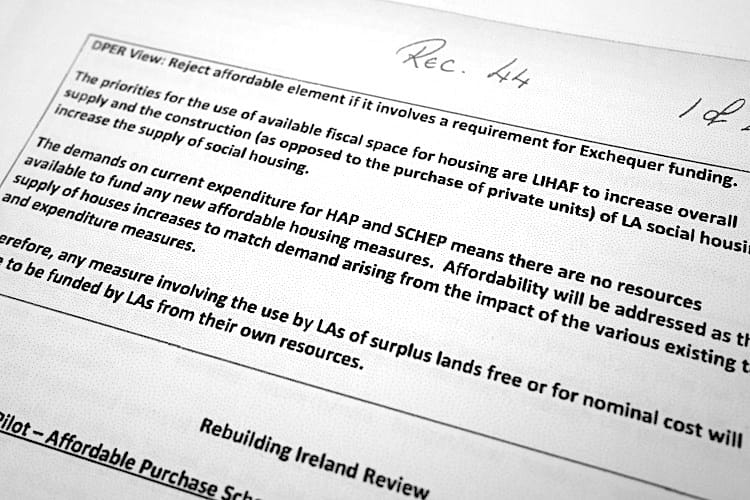

Other measures submitted by the Department of Housing in September 2017 as part of the review included general plans for affordable schemes for rent and purchase, using local authority land as the subsidy.

Another said it wanted to operate a pilot affordable housing scheme as part of the O’Devaney Gardens redevelopment scheme in central Dublin. The department and Dublin City Council had agreed that the homes there would be affordable purchase, it says. Lessons learnt could feed into other schemes.

A third proposal was to advance the pilot cost-rental project on Enniskerry Road. (That’s edging along, now, under the wings of the Housing Agency and Dún Laoghaire-Rathdown County Council.)

The Department of Public Expenditure gave similar responses to all of these proposals, noting that its priorities were funding through LIHAF to increase overall supply, and direct-build social housing.

The demands of the Housing Assistance Payment (HAP) scheme, and the Social Housing Current Expenditure Programme (SHCEP), whereby local authorities lease homes for social housing, mean “there are no resources available to fund any new affordable housing measures”, it also said.

“Affordability will be addressed as the supply of houses increases to match demand arising from the impact of the various existing tax and expenditure measures,” it says. So any measures involving local-authority land for free or nominal cost have to be funded by local authorities “from their own resources”.

Attempts to produce off-balance-sheet options – so those that wouldn’t add to the state’s deficit under EU fiscal rules – for cost-rental and affordable-rental proved unsuccessful, it says. Cost-rental wouldn’t appeal to private suppliers, “who can earn a greater return from the prevailing market rent”.

Given that approved housing bodies were likely to come on-balance sheet shortly, direct housing provision by local authorities “would be more efficient and provide better” value for money, it said.

You may also want to read “Why an Affordable Housing Scheme Promised Two Years Ago Was Shelved“, in this week’s edition.

Get our latest headlines in one of them, and recommendations for things to do in Dublin in the other.